At this point, the Philadelphia Architects Committee was very happy to have a promise of public support with overtones of establishment backing, and the citizens group was happy to have a plan. The working relationship for the future was left undefined. Some friction between the two groups would thus develop upon occasion but was always quickly resolved.

A first position paper had been prepared by a non-architect member of the Architects Committee, Eric Flaxenberg. It was a very strongly worded attack, not only upon the specific design, but also on highway engineers and urban freeways in general. It was felt that this attack was a little too broad-gauged, and that we would take on more enemies than we needed by using it. Yet the paper did serve as a starting point. It was felt by the committee, in all good faith, that the basic issues involved did not relate primarily to the Society Hill area, but more genuinely to Independence National Historical Park and Penn's Landing, and also to the continuance of the commercial core of the city down Market Street to the river.

When Martha Schober and Deborah Latta set up the March 3rd opening meeting through CCCP, it was determined that the key news event of the meeting would be an anticipation of the slight modifications soon to be publicized by the Bureau of Public Roads and then a statement that these modifications did not solve the basic design problem.

The meeting was held in the Downtown Club on Independence Square, overlooking Independence Hall and all the historic buildings leading down to the riverfront. A very good number of citizens and newsmen turned out, and I made a speech articulating our reasons why the embankment proposal must be scrapped, and the six-block cover proposal accepted. Frank Weise then presented his committee's drawings. At the last minute before the meeting, a name was picked: "Committee to Preserve Philadelphia's Historic Gateway." The term "gateway" had no particular association with the area but was used to dramatize the relationship between the historic city and the river from which from which it began.

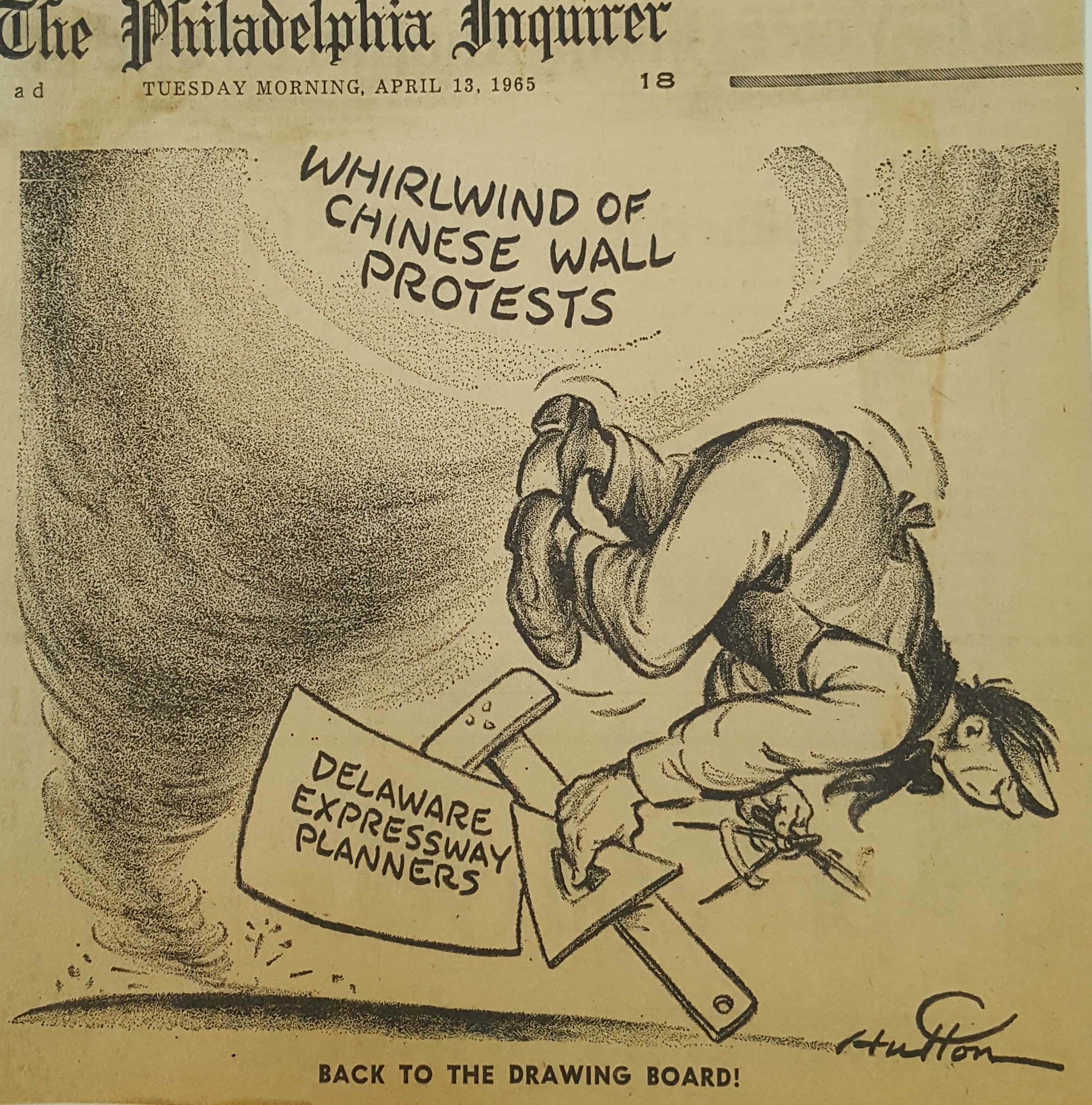

The news media gave us good coverage, and The Philadelphia Inquirer gave immediate editorial support, comparing the proposed design to the “Chinese Wall,” as the recently demolished Broad Street Station in the heart of Center City was called. The fight had begun.

An intensive, combined effort now began. The Architects Committee assumed the task of creating a model of its proposal, and a brochure describing it. The Gateway Committee began the job of gaining as much citizen support as possible. Our first question was, what do we ask those who agree with us to do? Mere protest is not enough, unless it is aimed where it will do the most good. Our target was quickly determined to be Pennsylvania Gov. William W. Scranton. We rejected an approach to the Secretary of Highways Harral, since presumably he would rule against us in any event. We also rejected any efforts in the direction of the US Bureau of Public Roads, since it could always say that the design was a matter primarily for the state. And we felt that Governor Scranton would be more amenable to political pressure (in the best sense) than any highway official.

At this point various people in public relations and the graphic arts, led by led primarily by Jan Mears (an art buyer for N.W. Ayer, the largest advertising firm in the city), prepared a small leaflet which would tell the story as quickly as possible and request readers to write to Gov. Scranton. Martha Schober and Deborah Latta began to contact as many organizations and key individuals as possible to obtain their endorsements. Copies of my March 3rd speech and the leaflet were sent to them. A petition committee was formed to obtain signatures. Posters were printed. A local real estate man donated an unused storefront at 1717 Walnut Street in Center City. It became a headquarters in the best political tradition and was a place where people came in to sign the petitions.

A large army of workers was now involved in all of the above tasks. Gregory Harvey and Ferdinand Schoettle went to work. Greg had superb writing ability and Ferd had worked for Senator Clark. The Ingersolls lent much moral support.

One key event was a luncheon meeting called by the president of Penn Mutual at the suggestion of Robert Dechert, the senior partner in my firm. Top executive officers of the major companies with offices in the Independence Square-Washington Square area were present. I told our story, and as a result a joint telegram was sent to Gov. Scranton urging a change in the highway design. This meeting was doubly important: one, it showed that our efforts had the backing of a substantial segment of the business community; and two, it served as the springboard for raising funds for our campaign from those businesses.

Meanwhile, I and certain others began a series of contacts in Washington. First, with two women active in Republican politics, a call was made upon Republican Senator Hugh D. Scott, who added his endorsement to Sen. Clark's. Through our committee's treasurer Jim O'Connor, another meeting was arranged with the Philadelphia congressional delegation. Its five members endorsed our plan and agreed to do what they could to help. In the rush of events, similar plans were made to address City Council and others, but these lost priority, and were never carried through. The model was finally unveiled in the lobby of the Philadelphia National Bank on April 7, 1965.

Counterproposal

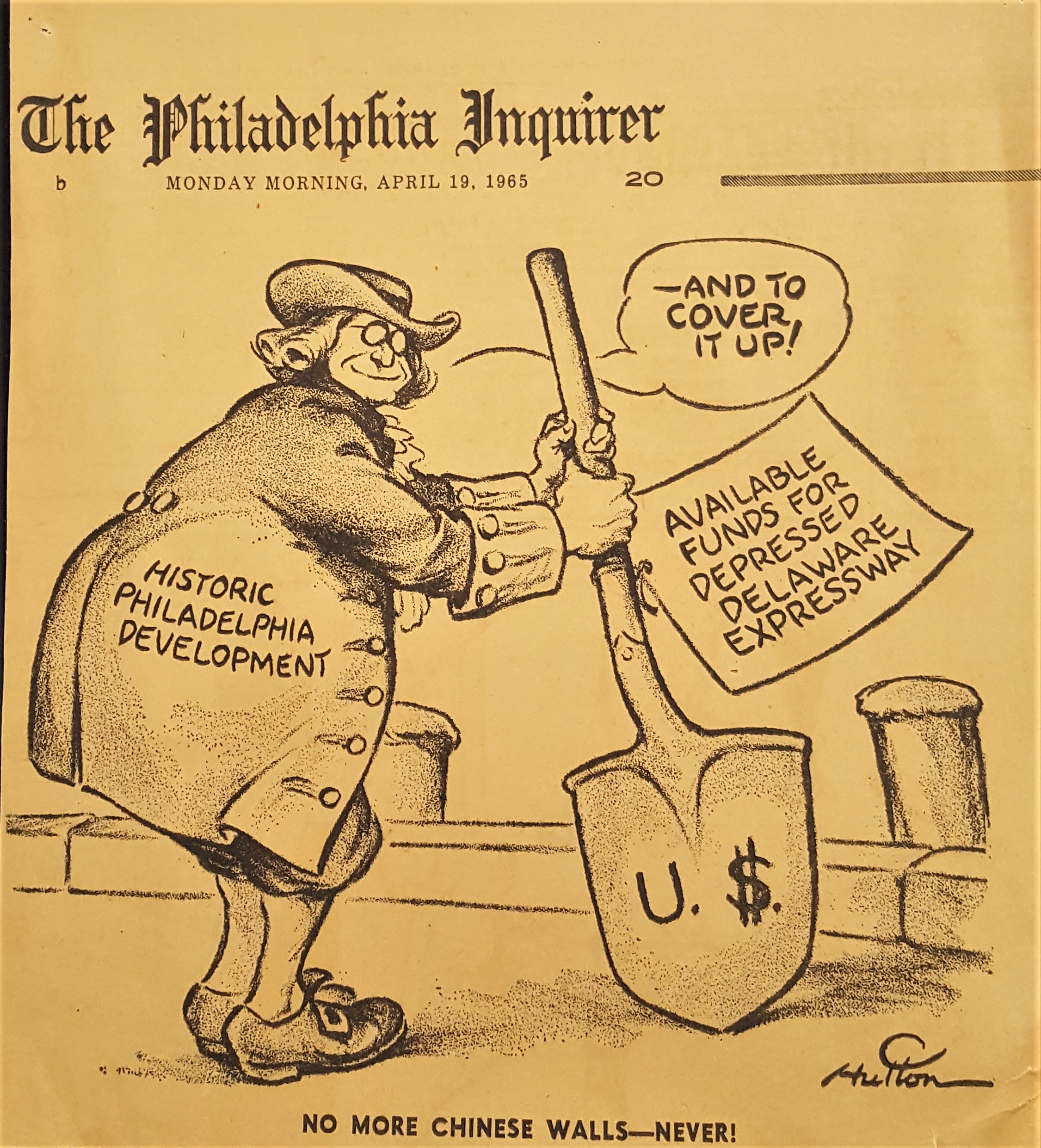

As a result of this blitzkrieg of editorial comment, citizen letters, petitions (which were addressed to Governor Scranton, but not yet actually presented to anybody) and behind the scenes work by the OPDC, Secretary of Highways Harral called a meeting in Philadelphia on April 15 stating that it would be concerned with the Delaware Expressway. It was his hope that this meeting would end the design controversy. He had worked out with his consulting engineers Ammann & Whitney of New York City a plan which depressed the highway and put it below grade in the Society Hill section of the six blocks in question. The depression would center on Dock and Spruce Streets. Present at the meeting among others were: Philadelphia Mayor James H. J. Tate; Rex Whitton, administrator of the U. S. Bureau of Public Roads; representatives of Sen. Clark's and Sen. Scott's offices; William Slayton, head of the Urban Renewal Administration; representatives of OPDC; Mr. Bacon and Mr. Rafsky.

The Gateway Committee and the Architects Committee were not invited. I had been in touch with some of the engineers in the Highway Department, however, and had asked if they would like to have our model present. They agreed that this was possible, and our model was brought. Frank Weise also asked if he could come, and so the two of us appeared at the meeting. We wanted to observe and did not want to be called upon to speak, particularly since we were not quite sure what was going to happen. The meeting started, and we were each requested to speak for 5 min. Our presentations were poor. We were then asked to leave on the basis that this meeting was for government officials.

After we left, Mr. Harral presented his open trench proposal. It is my understanding that William Day, a leading banker and President of OPDC, said that the plan looked good to him. Mayor Tate apparently agreed, and the meeting was then open to the press. Mr. Whitton, Mr. Harral and Mayor Tate appeared together, and were photographed with an architectural rendering of the proposal. I suspect that most people left the meeting with the feeling that the fight was over and that the highway department had made a great gesture to the people in Society Hill, to preserve their view of the river.