At this point it looked as if OPDC would buy the compromise, and that the Gateway and Architects Committees would be left without their behind-the-scenes establishment support. This presented to us the biggest crisis of the fight. Frank Weise and I, excluded from the meeting, had been trying to find out from the public information officer of the Highway Department how much of the depression could be covered, and were presented with wildly conflicting answers. After the meeting, OPDC hinted that it wanted the Gateway Committee not to commit itself publicly until OPDC could decide its position. The Gateway Committee felt that it could not lose its momentum, however, and issued a statement, followed by letters to key officials, hailing the depression as a step in the right direction, but reserving ultimate approval of what was going on until assurance that a "substantial" part of the depression could be covered. The word "substantial" was picked because we wanted both to go as far as we could toward getting a six-block cover, yet not break completely with OPDC. This word would leave us enough maneuvering position for what the future would bring.

In the meantime, the Architects Committee was having problems of its own. All its attention had been diverted to the model, and its members had not been able to put together the brochures they had wanted. They also felt that they needed certain engineering consultation, mainly for cost analysis. Since they were strictly without funds, this had been difficult. They had contacted a number of highway engineering firms throughout the eastern seaboard but were turned down primarily because highway engineering firms get their business from highway departments and are not just about to aid a protest group. Meanwhile the Highway Department, which had called the covered scheme totally unfeasible, had begun to raise doubts at OPDC. They had obtained a very rough idea of the cost of the cover from an out-of-state contractor, but nothing that could be used in public debate at this point. Frank Weise found Earl P. Allabach, president of Allabach & Rennis, Inc., perhaps the best-known and most prestigious structural engineering firm in the city of Philadelphia. Since our problem was one primarily of concrete structure and not highway layout, it was determined that Mr. Allabach could be of help. He was approaching retirement and felt there was no jeopardy to his business and reputation by engaging in this fight. He did require a fee, however.

By late April, it finally became apparent that only about a block-and-a-half, or at the most two blocks, of the open trench could be covered. The Gateway Committee and the Architects Committee determined at once that they would continue to press for the six-block cover.

A crucial meeting was then arranged with the executive committee of OPDC, set for April 26. Mr. Weise, Mr. Allabach and I appeared to plead our case. I meantime had become more and more involved in the preparation of the brochure, partly on the suggestion of one of Philadelphia's congressman that a "brief," or a written argument, be prepared in addition to the architects' pictorial presentation. The articulation of the reasons for the six-block cover were becoming much clearer in my mind. In the meantime, I had also received word from Sen. Clark that he was still anxious to continue the fight. Armed with this word and with Allabach, who would put his engineering stamp of approval (we all hoped) on Weise's plan, we presented our case, and were allowed to remain for most of the discussion. There was sharp conflict at first, but it was finally decided that two questions must be answered: was our plan feasible, and how much would it cost? Allabach would give us the answer, and he should be allowed to proceed. Accordingly, Gov. Scranton was reached from the meeting, and a request was made that the Highway Department work with Allabach and the Architects Committee to answer these two questions. Once they were answered, OPDC, the state government and all interested persons could then make a definite decision on this matter. Those who wanted the open-ditch compromise rapidly felt at this point that the covered plan would cost too much and not be feasible. Those who wanted it hoped that they would be vindicated. Thus, at this point, at the very least OPDC did not formally agree to the open-trench proposal, and the Gateway and Architects Committees could continue their fight. The crisis was passed.

The preliminary meeting was arranged with Henry Harral so that we could present our story to him and obtain from him a certain necessary date before the basic agreement as to feasibility and cost could be achieved. What started as one meeting on April 30 became a series where data was exchanged back and forth between the highway department and their consulting engineers and Allabach and Weise. The meetings became increasingly friendly, particularly on the professional engineering level. Finally, toward late summer, Allabach felt assured that agreement as to feasibility was achieved and the only problem was one of cost. There was a sharp disagreement on certain cost factors between Amman & Whitney and Allabach.

During the course of these meetings the Bureau of Public Roads announced that it would provide its share of the additional funds necessary for the open trench proposal (as distinguished from the original embankment proposal).

In the meantime, certain members of the Gateway committee and of the Architects Committee were working on the brochure, which gradually began to emerge. There were all sorts of internal conflicts as to graphics, emphasis, layout and the like, but in the heat of discussion these were all resolved. Martha Schober and her workers had continued the enlistment of endorsing organizations, all to be listed in the brochure. Very special effort had been aimed at the Greater Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce and on suburban groups; these were included. A final draft of the brochure was ready, awaiting only the outcome of the Allabach-Highway Department studies.

OPDC now formed a committee on the expressway issue, and former Mayor Richardson Dilworth was made its chairman. All members of the committee were very sympathetic to the six-block cover. It should be noted that the Ingersolls, who were on this committee, both played key roles in enlisting complete OPDC support.

Finally, in October of 1965 Henry Harral, in a letter addressed to the Gateway Committee and to OPDC, agreed that the plan was geometrically and structurally feasible, but required certain modifications to become feasible from an operating point of view. Adding these modifications produced a total additional cost over the open-trench proposal of about $25 million as contrasted with the $11 million figure outlined by Allabach. At this point the Gateway Committee, the Architects Committee and the OPDC committee agreed that they would accept a higher cost figure. Our thinking was that if we did not accept it, argument as to the correct cost would go on forever, and also from the general feeling that the man on the street, even the sophisticated man on the street, does not really appreciate the difference between $11 and $25 million when it comes to a major public improvement. Accordingly, the decision was made to press for the cover at a $25 million price and the job of enlisting public support was handed back to the Gateway Committee.

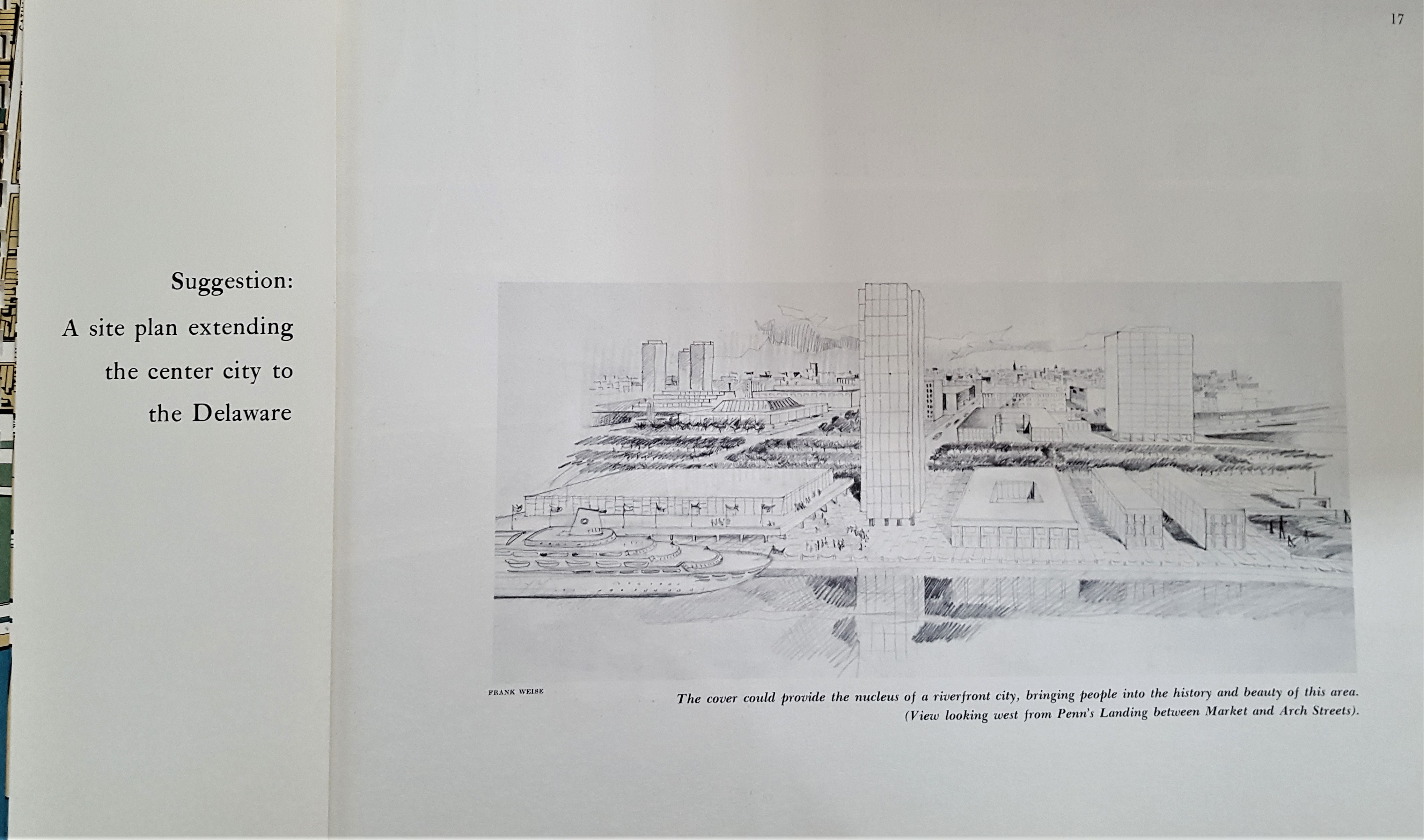

On December 16, 1965 the second public meeting was held. The purpose was to announce that the cover was feasible and that it would cost $25 million. The committee took the position that this increased cost should be paid from the Interstate Highway Trust Fund – that is, 10% from state highway sources and 90% from federal highway sources. The brochure was issued, and the plan described.

The brochure was mailed to all members of Philadelphia's City Council, to all Philadelphia legislators in Harrisburg, to all the Philadelphia congressional delegation, to the two senators, to all of the local news media, into a long list of civic leaders, primarily the boards of directors of OPDC, the Greater Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce and the Greater Philadelphia Movement. We asked recipients of the brochure to write to Governor Scranton and to Rex Whitton, Director of the Federal Bureau of Roads in Washington.

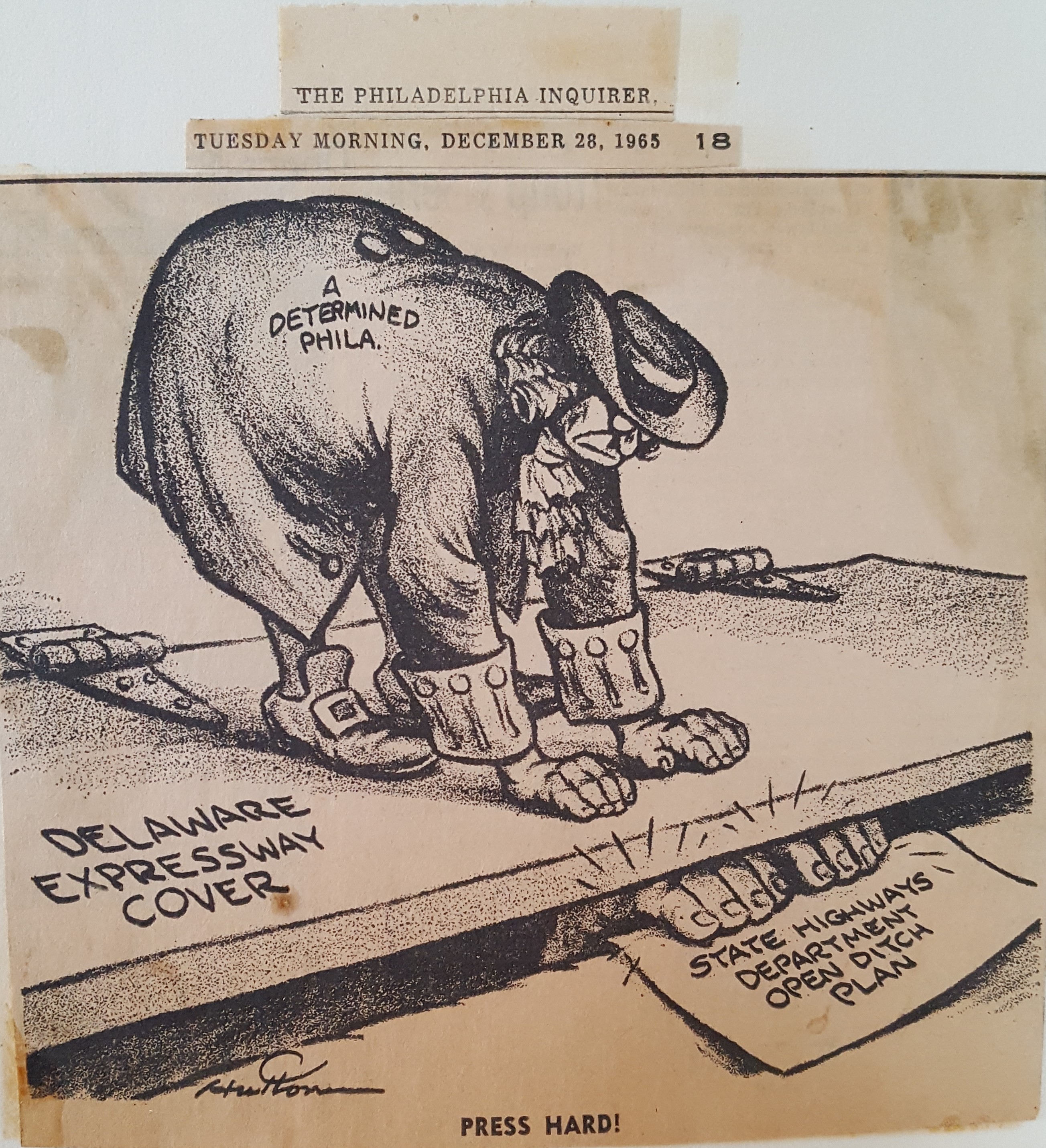

The blitzkrieg started again. Newspaper and TV editorial support, now including The Evening Bulletin, was quickly forthcoming. Virginia Knauer, a Republican councilwoman with a particular interest in Society Hill, introduced a resolution seeking the cover, and City Council passed this unanimously. Renewed expressions of support were obtained from Senators Clark and Scott. Richard S. Schweiker, a congressman from the suburbs, added his approval. OPDC itself formally endorsed the Gateway proposal for the first time.

Apparently, the brochure had its effect, because a great many letters began to go to Governor Scranton's office, asking for the cover.

Victory

The governor appeared quite sympathetic with the basic story. His problem was primarily one of financing, plus dealing with a highway secretary appointed to the job and who had committed himself against the cover. After several weeks of suspense Gov. Scranton said that his administration would approve the cover if the 10% state share would come out of highway monies previously allocated to Philadelphia projects. Mr. Ingersoll, Mr. Rafsky and I then called upon Philadelphia's Mayor Tate and told him of the importance of this matter. Mr. Rafsky suggested that the 10% be taken from the widening of Wissahickon Avenue, which could always be postponed for a later time, whereas the cover could never be postponed. Mayor Tate finally agreed to this, and with his action Gov. Scranton then made the proposal a part of the Pennsylvania Highway Department's official design.

Defeat

The next step was to persuade the federal Bureau of Public Roads to add its 90% share. Sen. Clark arranged a meeting in the office of Mr. Whitton's boss, Secretary of Commerce John T. Connor. This meeting was held on March 1, 1966. In attendance were Secretary Connor and Senators Clark and Scott plus Alan Boyd, then an undersecretary (later to become Secretary of Transportation), Rex Whitton, Anthony Zecca (representing Mayor Tate), Henry Harral, Messrs. Day, Saunders and Rafsky for OPDC, Earl Allabach and myself. I was called upon to tell our story, backed up in very strong words by Sen. Clark, Sen. Scott and Mr. Day. When Secretary Connor turned to Mr. Harral, the latter said that the official position of the Commonwealth was in favor of the covered design, but that he would be remiss in his duties as a highway secretary if he did not give his personal view. He then launched into a savage five-minute attack upon the covered design. I could not help but feel somewhat paranoid about highway officials at this point. Some of us came to the conclusion that through the American Society of State Highway Officials (ASSHO), the Road Users Conference and similar organizations, there was a conspiracy at all levels of government to keep all but highway engineers out of highway planning.

We left the meeting somewhat depressed. Word was immediately gotten to Scranton that his administration had not presented the plan as he had promised it would be, and he sent a telegram to Connor reiterating the official administrative position in favor of the cover and promising the 10% state share. Again, there was a period of suspense, after which it was announced by Secretary Connor that the federal government would not have the necessary 90%. Thus, the cover would not be financed as part of the interstate highway system. Mr. Whitton's accompanying letter offered only a grotesque walkway to Philadelphia.