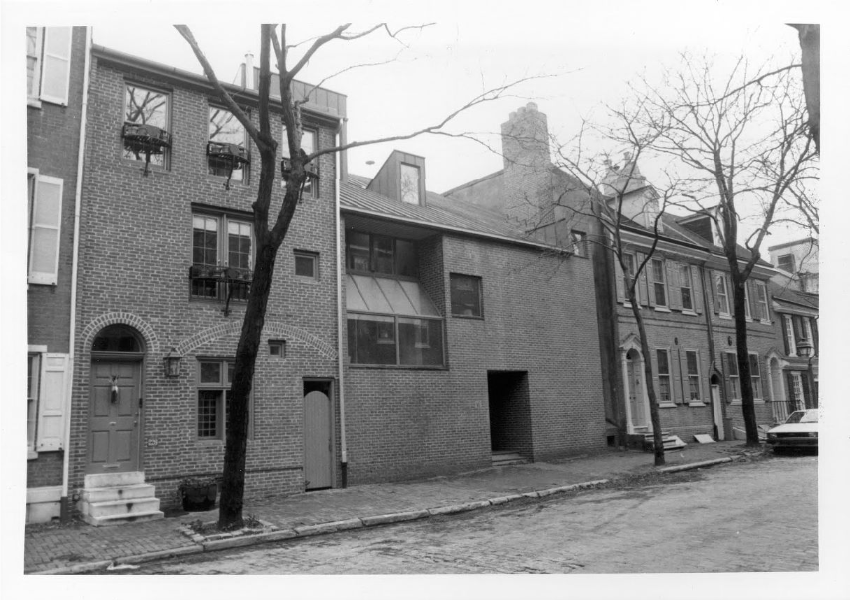

This double-lot property contains a three-story brown brick contemporary row house designed by Mitchell/Giurgola Architects ca. 1970. Before urban renewal, the site had been home to a four-story row house and an empty lot. Lynne and Franklin Roberts purchased these properties in 1965 for $6,400 and commissioned the new house in which they still reside today.

Lynne and Franklin Roberts married in 1959 and moved to the neighborhood in 1961, after subletting an apartment in the Rittenhouse Square area of the city. They were excited by the energy of the area, but arrived too late to purchase one of the larger properties. So they initially purchased 222 Delancey Street, half of a four-story twin with fire escapes running up the façade. They worked with local developers, Van Arkel and Moss, to remodel the shell—which had most recently been a rooming house—into a single-family house. A few years later, with two children of their own, they sought out a larger residence. The opportunity to build new construction a few doors down, at 228-230 Delancey Street, met their needs.

The Robertses describe the neighborhood of the 1960s and ‘70s as very social. There were annual block parties when they closed off the street, impromptu dinner parties, and neighbors often stopping by each other’s homes for a drink. Children roamed between residences as well, and a babysitting cooperative officially spread out the child care. Several of the women were also active the in the local public elementary school, McCall. Franklin Roberts served as the third President of the Society Hill Civic Association, a group formed largely by new residents to the area. During his leadership, he opened Three Bears Park, located on the 300 block of Delancey Street. The park was a popular meeting space for families with young children.

Lynne recalled how the neighborhood changed over time. Early on in their tenure on Delancey Street, a neighboring property was a “tenement” occupied by transient renters. A more professional group gradually moved in, however. These included “first artists and advertising people, then architects, and then lawyers, and finally, business people.”

Lynne described how they came to work with the Mitchell/Giurgola firm: “We didn’t want a close friend designing the house or being involved in building, because we knew that that could be the end of close friendships. [Laughs] We asked Rody [Davies, an architect neighbor who had recently graduated from Penn], and we asked some other young architects for recommendations, and everyone said, ‘Oh, there’s this marvelous man out there named Romaldo Giurgola.’ That’s how we heard about Aldo Giurgola…. We pretty much gave him free rein, in the sense that we said, “We want X number of bedrooms. We want a lot of backyard. We want…” – you know, gave him that sort of request and let him go. We’re pretty pleased with the result.

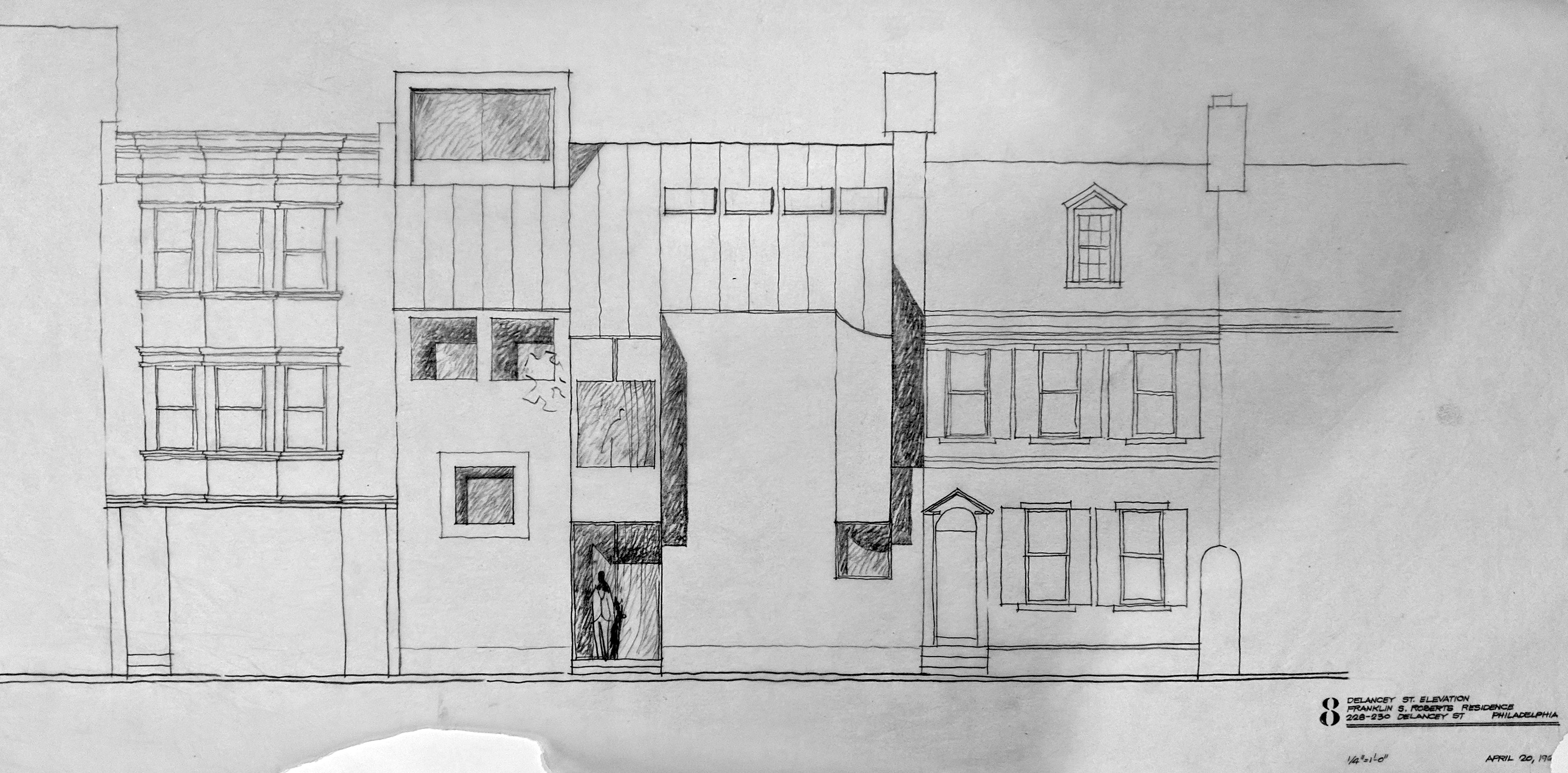

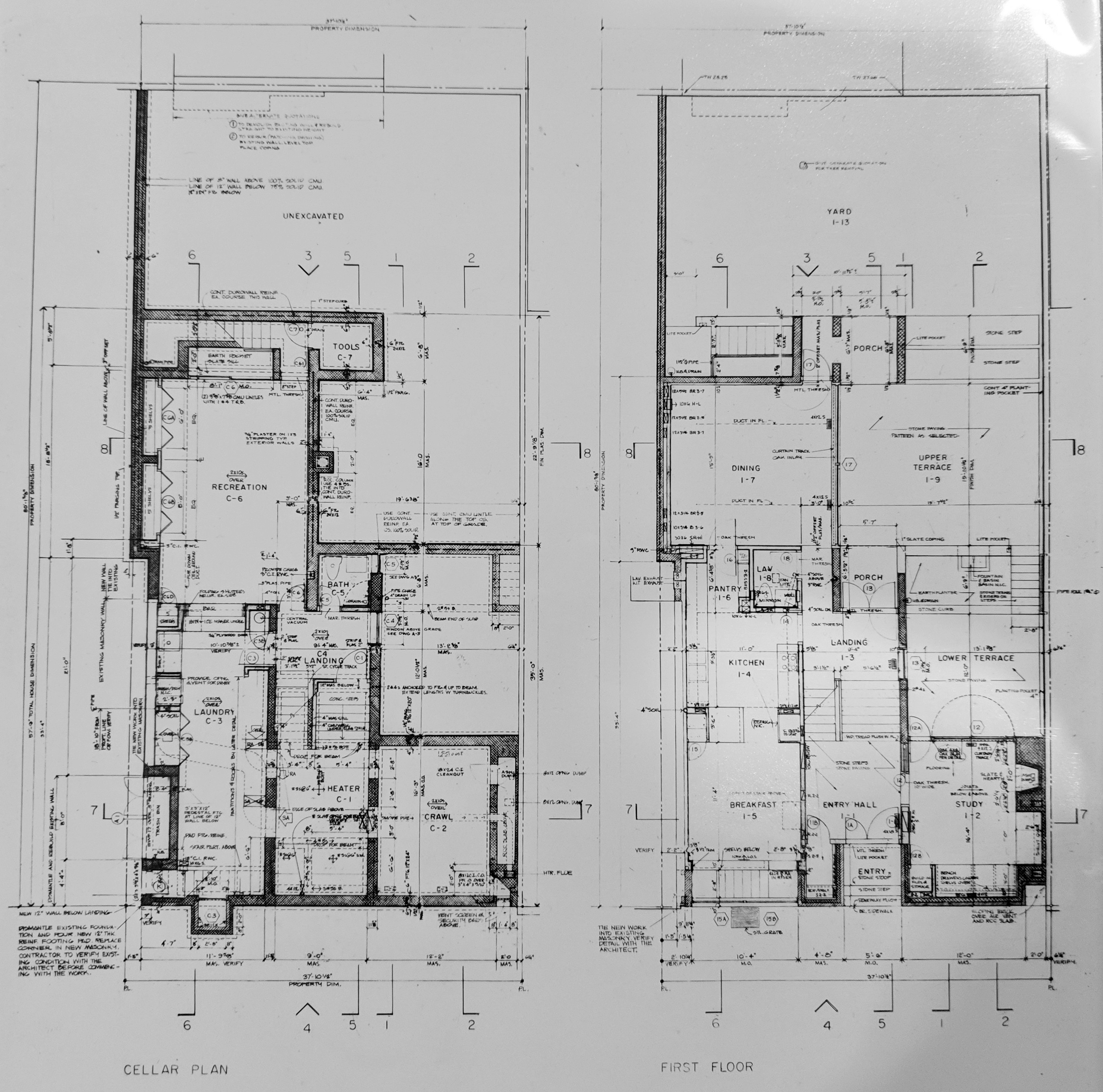

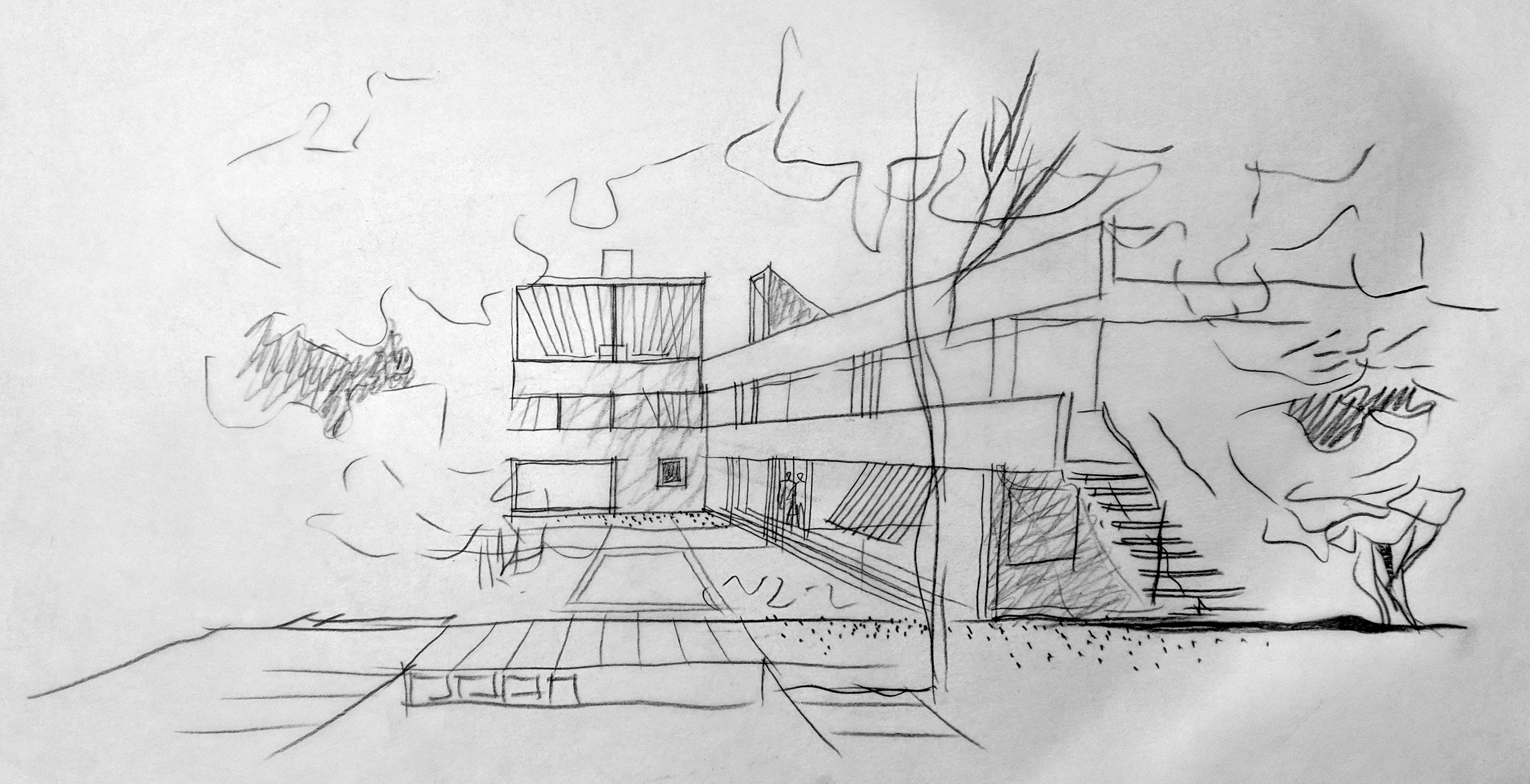

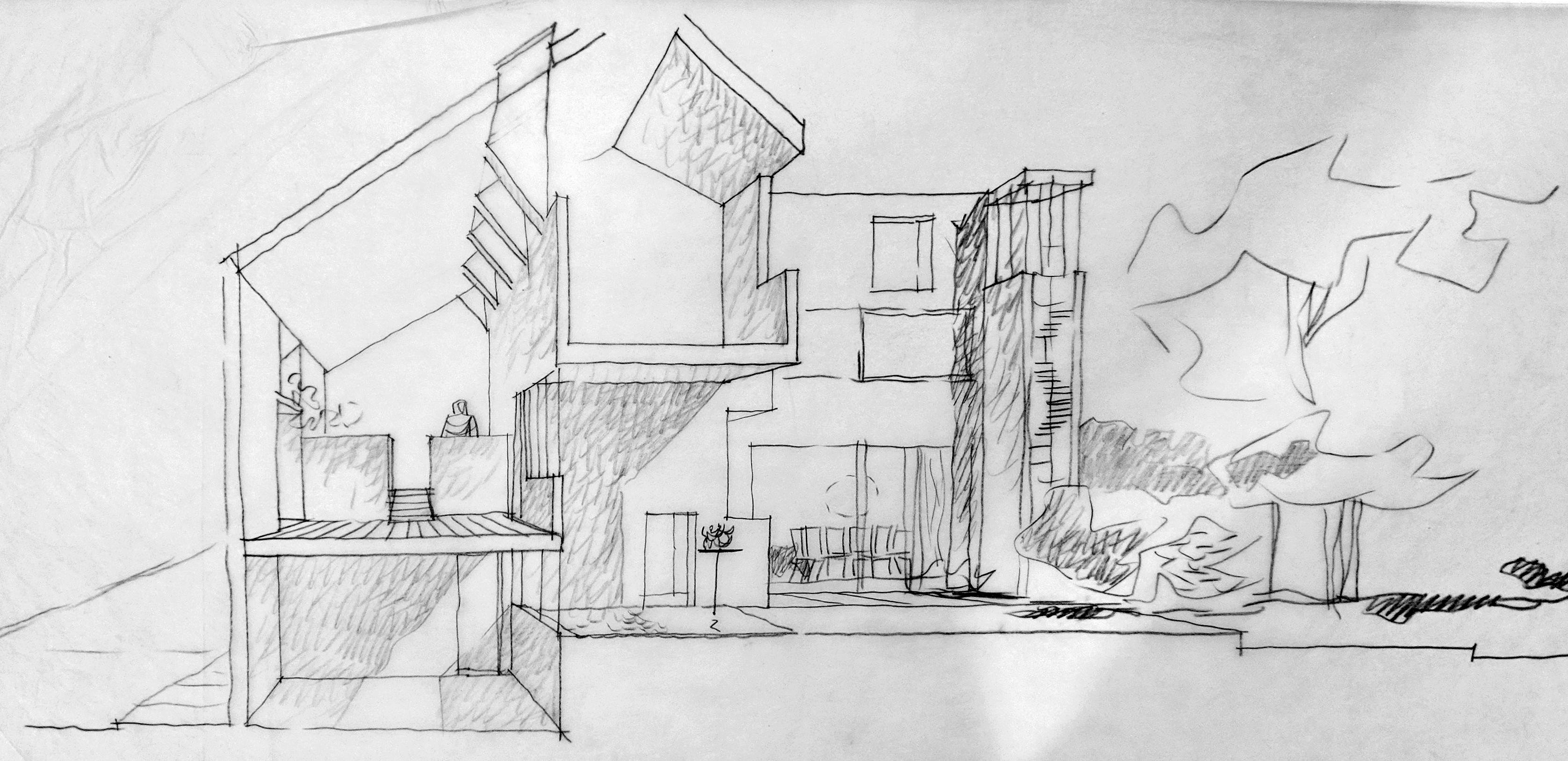

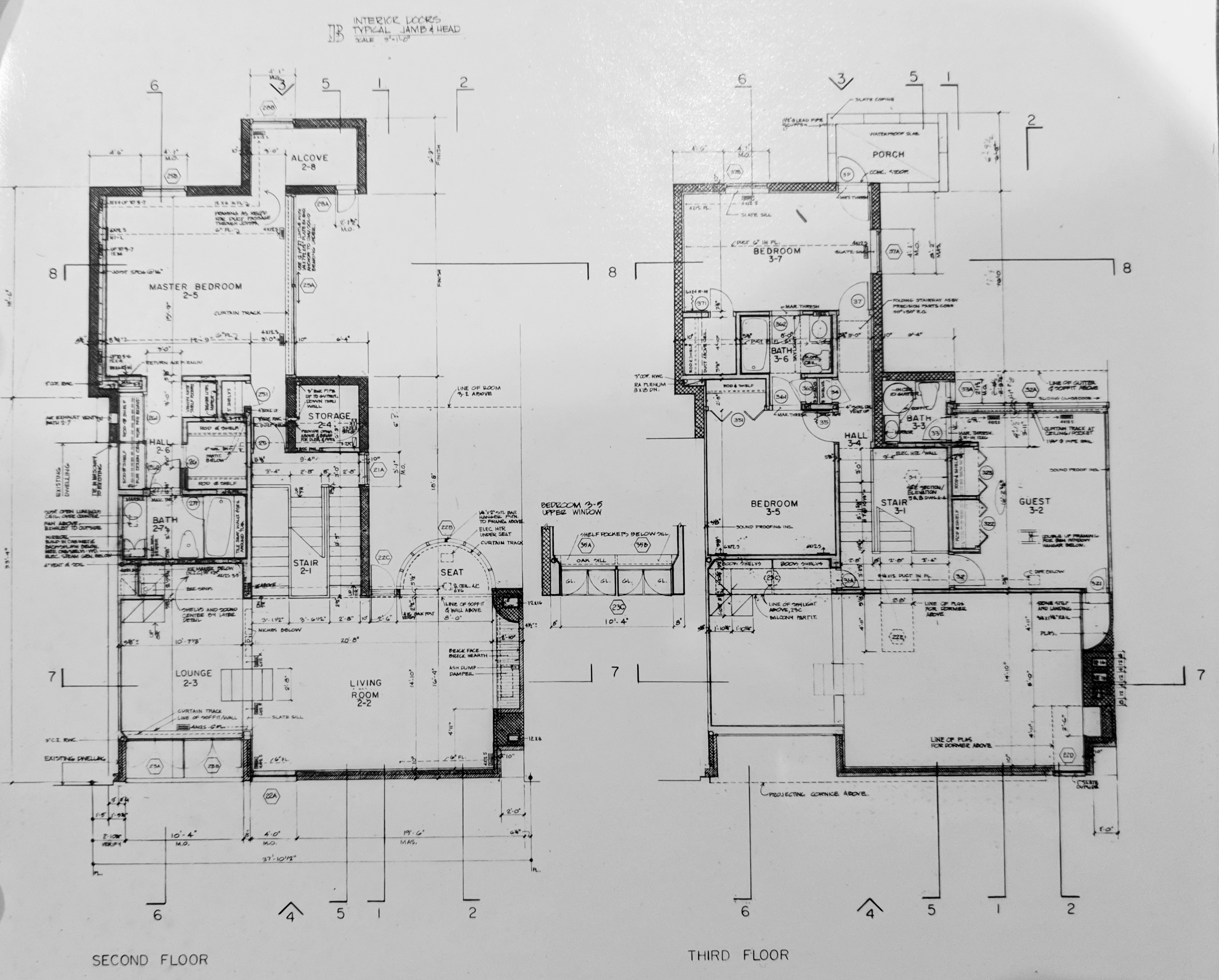

Giurgola’s design took advantage of the double lot to emphasize spaciousness and light—particularly toward the rear of the building. On the facade, he hoped to include a bow window that would afford a view up S American Street, but the city would not approve it. They wanted a flat front. The other element of the design that they rejected was his proposal to use stucco in front. Instead, like all of their neighbors, they had to use brick. Otherwise, however, the Robertses do not recall many restrictions on the house design.

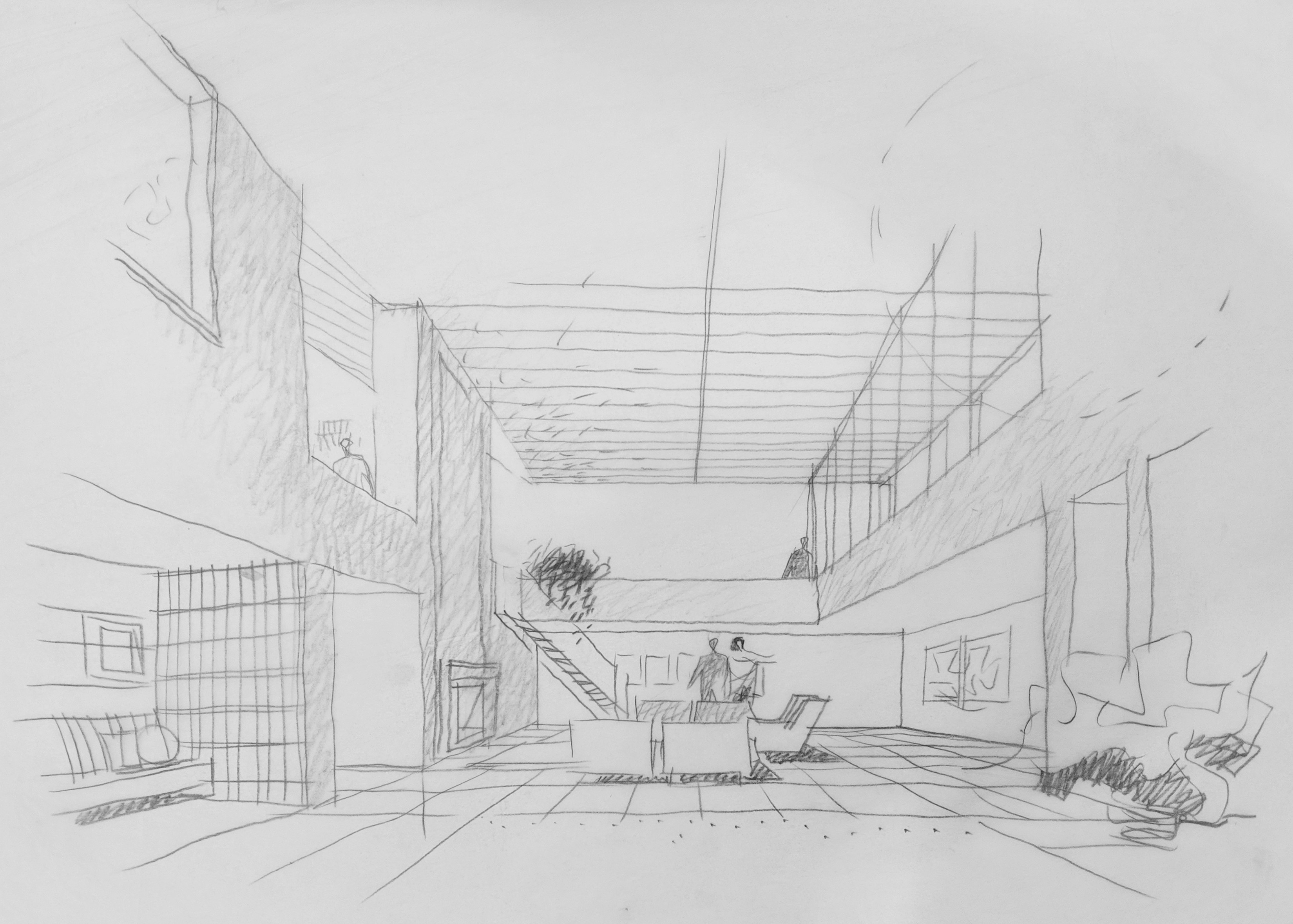

On the interior, Giurgola incorporated multiple levels and stairways, creating a multitude of spaces. In some ways he was creating set, in keeping with his clients’ occupations in theater and entertainment. Franklin wrote and performed plays, while Lynne worked at the Theater of the Living Arts, on South Street. Giurgola even included an interior balconette in the house.

This narrative draws upon oral history interviews with Lynne Roberts and Franklin Roberts contained within the Project Philadelphia 19106 collection at the Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries, and on Preserving Society Hill.