“My God, you’re going to live here?” was the reaction of one of Lynne’s friends when he saw 222 Delancey Street, the shell that Lynne and her husband Franklin had recently bought. She says that was pretty much the attitude of their suburban friends to the idea of their moving to Society Hill. The year was 1961, early days in redevelopment, and the neighborhood was still a work in progress. Lynne describes some of the features of the neighborhood at the time and names some of the people who had bought and fixed up derelict houses even earlier. By 1966, needing a bigger house, they bought two adjacent properties: one a vacant lot, and one with a house they demolished to build a new house. They engaged a promising young architect named Romaldo Giurgola. They sold 222 Delancey. While they were waiting for their new house to be finished, they lived in the curate’s apartment on the top floor of St. Peter’s Church parish house at 313 Pine Street. As more newcomers arrived, they all understood why they wanted to live in that neighborhood. They got to know people who had lived there a long time, formed a residents’ association, planted community gardens, organized the residents to oppose the elevation of I-95 where it passed Society Hill and to oppose the construction of the Crosstown expressway along South Street, supported the neighborhood elementary school and sent their children there when teachers were not on strike, took their kids to Three Bears Park, established the baby-sitting co-op, and had block parties regularly. They formed lasting friendships.

DS: The narrator is Lynne Roberts. The interviewer is Dorothy Stevens. The location of the interview is at 228 Delancey Street, and the date is February 2, 2008.

[Tape is turned off, then on again]

DS: Lynne, tell me, when did you come to this neighborhood?

LR: To live or to look?

DS: Both.

LR: Well, it was, I believe, in January or February of 1961, and ironically and amusingly, though I don’t think they remember, the Erdmans, the Davieses and the Eimans were wandering around that same time looking at houses. Rody [Roland Davies] was recently graduated from Penn Architecture school, and they were all looking around. We moved in the end of ’61, having found a house, which was 222 Delancey. It had fire escapes across the façade. (1:00)

DS: In the front?

LR: In the front. It was a twin with 224 [Delancey Street]. They had joint fire escapes. There was, of course, no plumbing. The smell was unbelievable [Laughs] in terms of the urine smell. It had been a boarding house with, I believe, perhaps, 224 [Delancey] – we’re not clear about that – but it had been empty. It was now a shell. The only historic things that remained were the side door going out to the yard – there was a yard – with two side panels, late nineteenth-century panels. It had a marble, sort of not a fireplace, but what was a stove, (2:00) I think, a stove thing, which was obviously a later addition. Of course, we didn’t keep that. We were lucky enough to find a mantle that was of the period. Those were the only two historic things in the house, basically.

DS: The house had been vacant for a while?

LR: I believe it had been – you couldn’t live there with that smell!

DS: It had been – well, right.

LR: It was a shell. It had stairs to the upstairs. It had the coal room which may have been a double-duty outhouse. I can’t quite figure it out. In the back, there was a room, a sort of stone room, and there was a shed, sort of, on top of it.

DS: Attached to the building?

LR: Attached to the building. We made the shed, the downstairs room, (3:00) into our breakfast room. Tom Van Arkel and Urban Moss were wandering around looking – deciding to be builders – and so they were our builder for the house. It was a very basic design that we kind of co-designed with them.

DS: Originally, when you walked into the house, was there a long hall? With a parlor?

LR: Well, yes. There was a short hall and a parlor, but it was a very short hall and an open room.

DS: One big open room?

LR: One big open room with a fireplace, and I mean, as I say, with this marble thing which was probably 1920s, and pretty much nothing else.

DS: Upstairs was just open?

LR: Right.

DS: Who did you buy it from?

LR: We bought it from the Redevelopment Authority. (4:00)

DS: Urban Moss –

LR: Tom Van Arkel and Urban Moss were our builders. I wish I could remember – when you talk to Franklin [Roberts] if you remember – at that time, and this was true for all of us, there was only one bank or group that would mortgage houses down here. I can’t remember their name, but he will remember. They were the only ones who would consider taking mortgages for what was – well, next door, here – we had a tenement, which was a very nice group of people, and a guy in an old, green truck would come by every week and collect their rent. The house [at] 224 [Delancey] was, of course, empty. There was the American Legion across the way. What is his name? I can’t remember (5:00) his name, who lived up – and I remembered it earlier today when I was going to tell you about him.

DS: Reardon?

LR: Well, yes, they – the Reardons were here. [sound of telephone ringing]

[Tape is turned off, then on again]

LR: I can’t remember his name, but Frank will remember. A broken-down shack. The Nicholsons [Arnold and Elizabeth] were here, Maureen Murdoch was here, and Bertha was here.

DS: Bertha von Moschzisker?

LR: Bertha von Moschzisker was here.

DS: That broken-down shack was 240 Delancey?

LR: Yes. Teddy – I guess Teddy and Debbie were here. Were they?

DS: Newbold? Yes.

LR: Right. Yes, and they were the new neighbors; that was all the new neighbors. However, we had been looking – thinking about this, because in ’60 a friend of Franklin’s lived in what was to be Bob Trump’s house. He had rented it [out], those two little houses. (6:00)

DS: On the south side of Delancey?

LR: Exactly. He was living there – I can’t remember his name, either. He worked for the Inquirer, and he was renting that house. I don’t know who had restored it, but it was obviously restored at that point. Franklin was fascinated with the neighborhood. Where Delancey Mews is now was a gas station with grass. Delancey Park was the iron mongers workers, since the Food Distribution Center had moved out, there was an empty grass where we used to have Billy Newbold’s birthday parties with pony rides. The only (7:00) construction down there was a huge Quaker City storage facility.

DS: Which was on the south side of Front Street?

LR: Exactly. Well, the west – not the south side.

DS: The west side?

LR: No, it was on this side of Front Street. Front Street still ran [north and south] and it was on the west side of Front Street on that big lot. In fact, when I-95 was being considered and we were all up in arms, it was because of the elevation [of the highway]. Teddy [Newbold] and Bill [Eiman] and I went down [to the Quaker City Storage building] and took a measuring, and [they] said, “See, Lynne, it won’t (8:00) be that bad on the Quaker City [building] – they showed me where it would be on the building.

That’s when Jan Mears and I got involved and worked very hard with Urban Moss to get the [scale] model of what [the City Planning Commission] was proposing. We were outraged, because Teddy and Bill both said, “Oh, nothing can be done.” Jan and I started that movement, and then Stanhope [Browne] and Martha Shober and everybody took over and really did a bang-up job. Jan and I just started it by getting the model – with Urban Moss – [on display] in one of the bank buildings, so everyone could see how horrible this [proposed highway] elevation would be.

DS: Yes, yes. Your story is why – that’s your story about why you came to this neighborhood? It was Franklin and his – (9:00)

LR: We were married at the end of ’59, and we were living in a rented [sub-let] apartment at 2038 Locust Street. We decided this was where we wanted to be. We both are city dwellers; so [since the sub-let was temporary] that was perfect.

DS: Did you work in the city?

LR: Yes.

DS: You both worked in the city?

LR: Yes.

DS: Now, what did you pay for the house – for the shell?

LR: It was $7,000 to $9,000. (10:00)

DS: Do you remember the taxes at that time?

LR: No.

DS: What did you do with the house? How did you fix it up?

LR: Well, Urban Moss and Tom Van Arkel were people we knew, had met, and they were developers. We didn’t know anything. This was not our line or our field. We talked to Rody a bit.

DS: Rody Davies?

LR: Rody Davies, who is an architect. And also, I think, some friends of Franklin’s. We did a fairly simple design. I had some ideas. [Since] there (11:00) wasn’t room on the first floor for a guest bathroom, we made a double bathroom on the second floor, where the front could be closed off and just be a guest bathroom, and the tub and everything else was in the back. We realized from the ceilings that the second floor had been the living room, and we were not going to do that. We had our living room and dining area on the first floor and made the long sort of alley, which was half the width of the house, the kitchen. It was very basic, simple, looking at what was, and saying here’s how we can do it. Cost was a factor, obviously. (12:00) The dormer area became the playroom for people like – let’s see, how many Stevenses and how many Robertses in our play group? Greg [Stevens] was very talented artistically and he drew a wonderful thing on the wall. [Laughs]

DS: You didn’t stay in this house?

LR: No, because after we had kids –

DS: You had two children.

LR: We had two children, and we knew we wanted to stay in the neighborhood – this was in ’66, ’67 – We knew we wanted to stay in the neighborhood, but we thought the house would be too small for what we wanted. At that time, there was an empty (13:00) lot at what was 226 [Delancey Street], I guess. Isn’t that what we are? 226?

DS: 228.

LR: Right. 228 [Delancey Street] was under agreement [of sale] with the Redevelopment Authority, and in fact, that [house] really helped keep this neighborhood safe. There was a young lady who lived there [with] her mother, and her mother used to pimp for her. We would see the policemen coming out the door, zipping up. It was – it was – and I kept saying, “Isn’t this wonderful? How safe our neighborhood is?” [Laughs] I mean, we had John, who lived on American Street, who was unfortunately the neighborhood drunk, but he knew who was coming and going in the (14:00) neighborhood, and he was kind of a good watchdog. Then we had the police occasionally walking by, because they were using the facilities and services of what was 228 [Delancey Street]…. We bought the empty lot [226 Delancey Street] from the Redevelopment Authority.

DS: Now, how much did that cost you? This would have been ’66?

LR: ’66, ’67.

LR: Yes, because we sold – it was at the time we sold 222 [Delancey Street]. We wanted to sell it before the spring – before the summer. That was when Martin Luther King had been killed, and we had all the riots. We had envisioned a long, hot summer. We sold 222 [Delancey Street] at probably somewhat less than we might have gotten had we not been very concerned about getting out before the summer. We were concerned that people might not want to live in the city under those circumstances. The 228 Delancey Street house was not finished. The parish house at St. Peter’s was empty. The curate who would have lived upstairs in the parish house was—no, they didn’t have a curate; so we arranged—because they were happy to have (16:00) someone kind of look after the parish house, we arranged to have the apartment, the curate’s apartment, in the parish house.

DS: That’s 313 Pine [Street]?

LR: That’s 313 Pine.

DS: Do you remember how much you paid for the land?

LR: No.

DS: Do you remember how much you paid for the construction of the house?

LR: No.

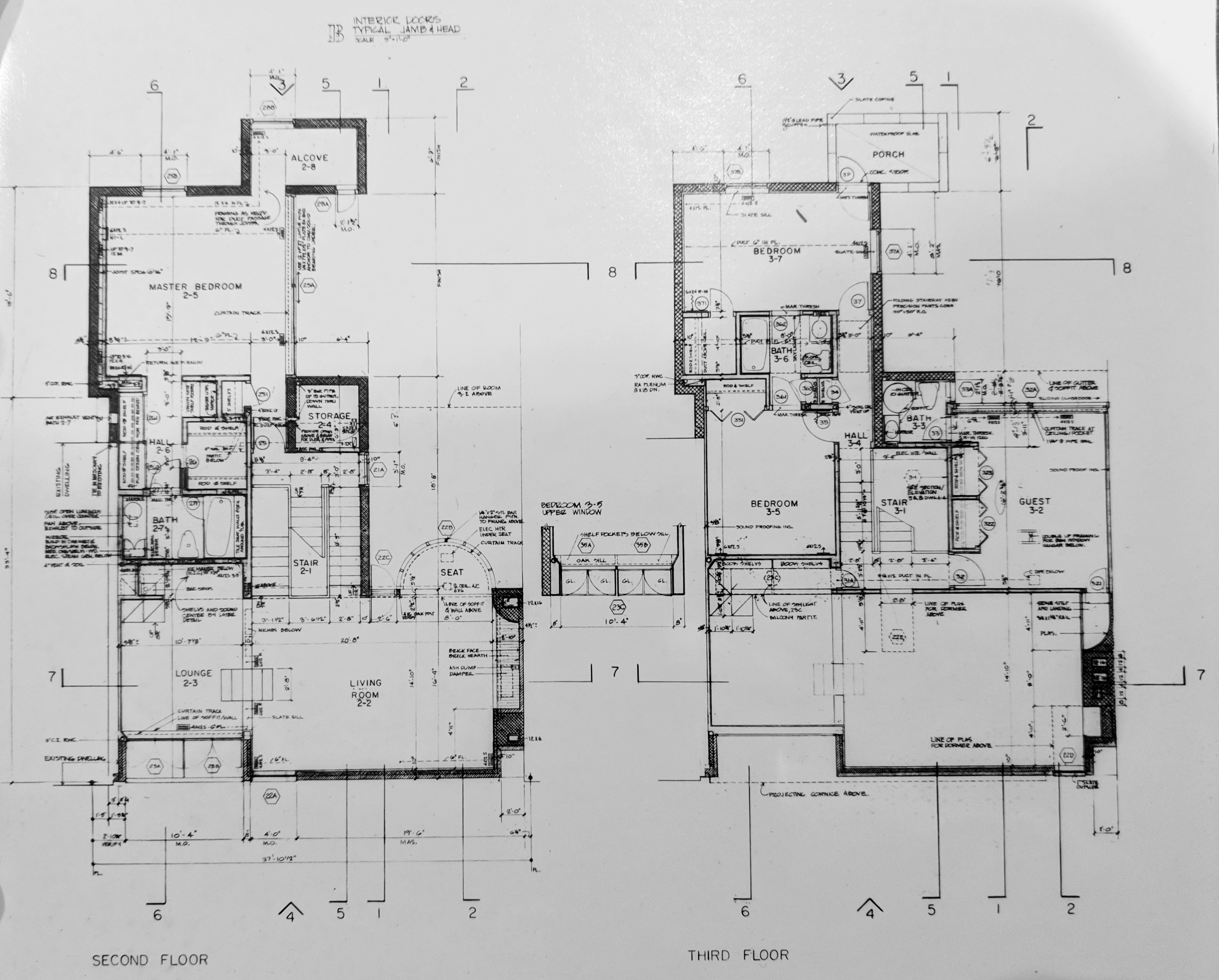

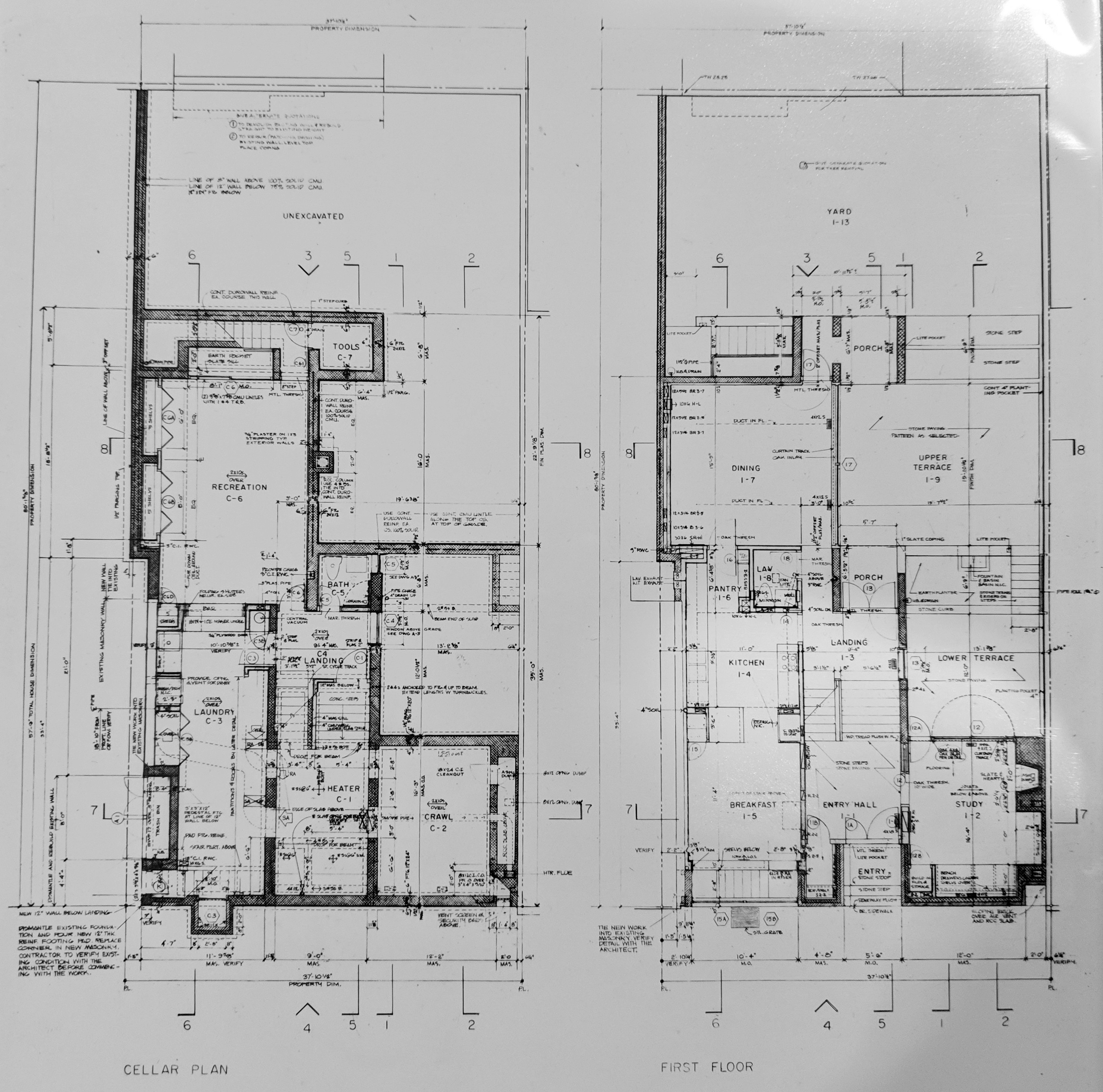

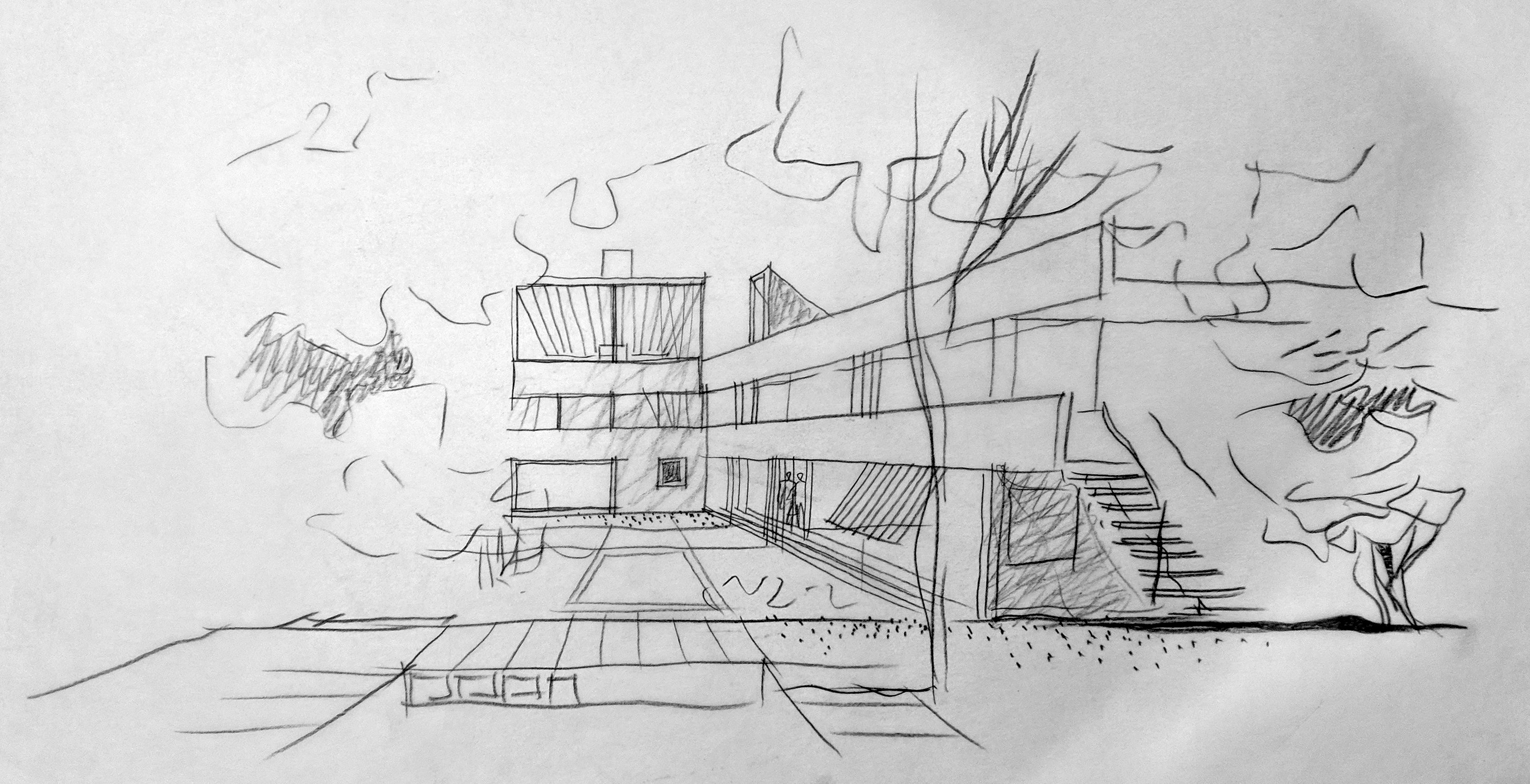

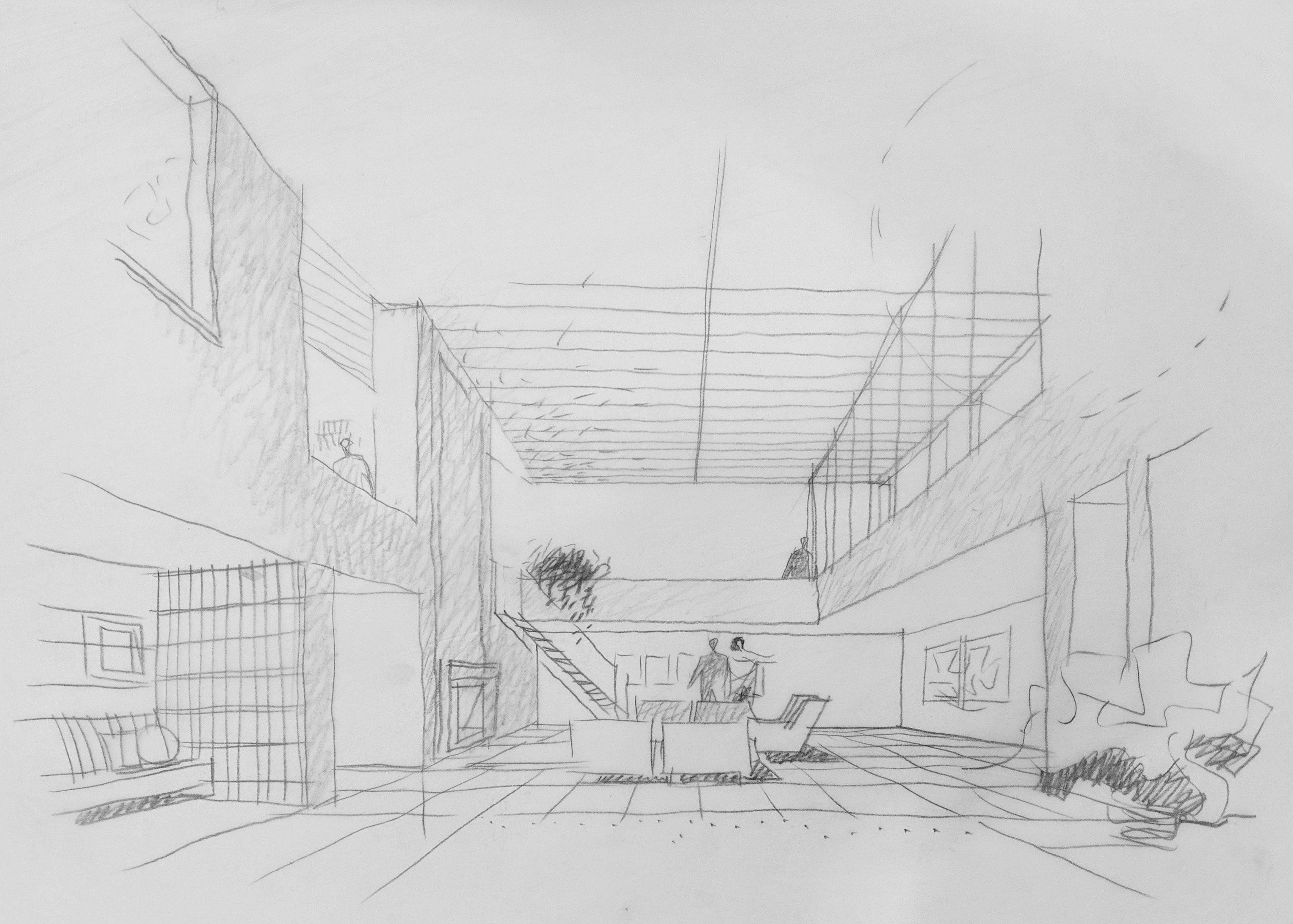

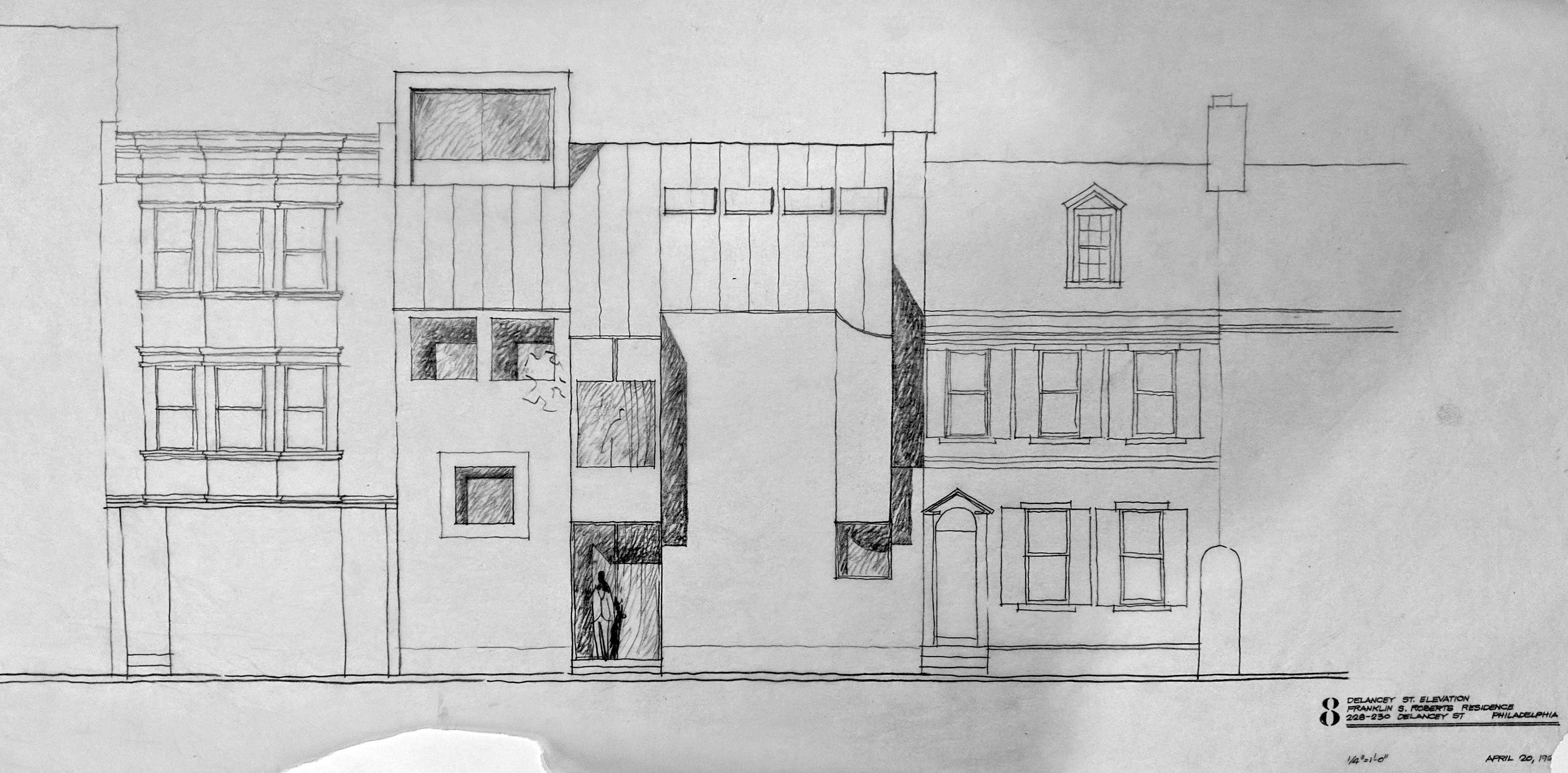

DS: Who designed this house for you?

LR: We didn’t want a close friend designing the house or being involved in building, because we knew that that could be the end of close friendships. [Laughs] We asked Rody [Davies], and we asked some other young (17:00) architects for recommendations, and everyone said, “Oh, there’s this marvelous man out there named Romaldo Giurgola.” That’s how we heard about Aldo Giurgola…. We pretty much gave him free rein, in the sense that we said, “We want x number (18:00) of bedrooms. We want a lot of back yard. We want…” – you know, gave him that sort of request and let him go. We’re pretty pleased with the result. He kept thinking we should have a pool. I wonder where he got that idea, Dottie. He kept saying, “Where will the pool be?” We said, “No. We had one down the street. We didn’t need one.” [Laughs] He was pretty pleased with the house. One problem was, at that time, a lot of architects were in love with industrial windows, and again – senior citizen moment – I can’t remember the name of those windows. Metal windows are certainly more efficient in the sense that you don’t have to repaint them all the time, nor (19:00) do you have to worry about the wood rotting. However, they conduct heat and cold like nobody’s business, [Laughs] being metal windows.

DS: Was the summer as steamy as you expected after Martin Luther King’s death?

LR: You know, I don’t recall. We were obviously concerned but by pricing it a little low, we were able to sell it quickly. The 228 Delancey house was not finished until 1970, five weeks before – no, two weeks before – Laura arrived. That’s how I remember [Laughs] and we moved in.

DS: What restrictions did the Redevelopment Authority put on your renovations when you had 222 Delancey? (20:00)

LR: Very few, because we were not really – other than cleaning up the façade and clearing the fire escapes – we were keeping the dormer – so that was very little. The restrictions were on this house. We had wanted to save money by having a stucco front. Of course, Mr. Kelly [John B. Kelly] had insisted that everybody in Philadelphia have brick houses, so that was the end of that. Aldo had envisioned the view down American Street in a certain way: he had designed (21:00) a bow window that would open from the top down, with sort of seats set in at the various floors, so that we could look up American Street. This bow window I didn’t particularly care for. It was too exposed for me, and I did not think that anybody would sit in the seat staring up American Street. The Historical Commission or the Art Commission or whatever commission said, no, no, it had to be a flat façade. [It] did not break my heart. I think Aldo was unhappy, because it was sort of his signature…. That’s really – the stucco and [the bow window] – were the only [issues]. We always planned to have the rooflines lined up with the houses –

DS: The houses on either side of you? (22:00)

LR: Right.

DS: Because you were going to be contemporary architecture, they didn’t want you to be set back from your two houses on the side?

LR: No, they never – was that a problem you had? Isn’t that interesting? Well, think of how many years later this was. You were?

DS: ‘64.

LR: ‘64, exactly. By ’67, ’68, that wasn’t a problem. No – there was no setback issue at all.

DS: Tell me the reaction of your family to this idea of first restoring a house and then building a house.

LR: Of course, by the time we built the house you all were here, and so my family was delighted with that idea, because they had met a number of you, and liked you all, thought it was kind of neat and exciting. 222 [Delancey Street] was a whole different (23:00) story. I can remember our friends from – actually an usher in our wedding, a fellow named George Robinette – coming into our house – to the shell – and saying at the top of his lungs, “My God, you’re going to live here?” That was pretty much the attitude of our suburban friends and other people. I can’t recall my parents. I’m from Cincinnati. I don’t think they were ever here.

DS: They didn’t come to see it?

LR: They came to see the house when it was finished, but not when it was started. In fact, there’s a very funny story. Do you remember when Stuart Lewis, the gourmet place, was around the corner, where what was going to be the ice cream parlor and whatever –

DS: On Second Street?

LR: On Second Street.

DS: Between Pine and Lombard. (24:00)

LR: The Ostranders were working there at that point. My parents came back from Europe and went around to get me some goodies. The next thing we know, we get a phone call. Apparently, I mean, it’s one of those small world things. As you know, the Ostranders are from Cincinnati, only we didn’t know each other there. [My father had] left his passport there [at the gourmet shop]. They’d seen my brother-in-law’s [name on the “in case of emergency” line.]

DS: Whose passport?

LR: My father’s. They’d seen my brother-in-law’s name, and they had gone to school with my brother-in-law in Cincinnati. They called Cincinnati and said, “We have Chester Martin’s passport here. He just left.” And so…when they called Billy, Billy [my brother-in-law] said to them, “He must be right around the corner. He’s staying (25:00) at my sister-in-law’s house.” They called us, and Daddy got his passport back, but it’s one of these things. I didn’t know the Ostranders were from Cincinnati. They didn’t know me, but they knew my brother-in-law. Just a very funny, small world kind of thing.

DS: It is. When your parents saw your renovation of 222 [Delancey Street], they were happy with it?

LR: They were okay with it.

DS: They were okay?

LR: They’re suburban people, and I mean, because Cincinnati’s a different construction. At that time, people didn’t live downtown, but the suburbs were much nearer to the city…. If I’d had them there while it was under construction, they would have been picking me up and taking me home. [Laughs]

DS: You knew that, so you didn’t have them?

LR: That’s right.

DS: Now, how about Frank’s parents? (26:00)

LR: Frank’s parents are from Strawberry Mansion. They had lived in a rowhouse all their lives. His parents – his mother has lived with like people all her life. Her major concern was wouldn’t I be lonely without people that she felt comfortable with. [Laughs] Other than that, they were not judgmental.

DS: They didn’t tell you how to do it? Did they help you at all? Financially.

LR: No.

DS: You didn’t have to get their approval.

LR: No, no, no.

DS: Your friends were behind you?

LR: Well, my new friends, my neighbors, of course. We had such a wonderful time, and you remember it as well as I do. When somebody’s kitchen was done, you’d go over and have dinner there. [Laughs] It was just a wonderfully, warm kind of collective. (27:00) When the Newbolds went to Mexico, Jane [Eiman] and I babysat Billy. I mean, Jane had most of the responsibility, but I’d go over there and help her. The one thing that I felt very badly about, and you may want to edit this –

DS: You want me to turn it off?

LR: Maybe.

[Tape is turned off, then on again]

DS: Tell me, do you have any photographs that you took of the area?

LR: Yes, we do, and we showed a lot of people the photographs. I’m wondering if we gave them to people, because Stanhope [Browne] is doing something at some point. We have photographs of the house as it was.

DS: Before –

LR: 222 [Delancey Street], before we did anything there, and I’m trying to think (28:00) of some other photographs.

DS: Of the neighborhood?

LR: Not as extensive as a lot of people do.

DS: But you have some?

LR: Yes.

DS: Can you think of any other stories about the neighborhood, the people. Did you interact with people who were born and raised here? Did you get to know them?

LR: The woman who lived – yes. The woman – and here we go again – who lived next door to Maureen –

DS: Murdoch, on the 200 block of Delancey, north side.

LR: Right. What was her name? A woman of Polish descent. The Schmidts we have known on and off, and because they have been so much a part of the neighborhood, it is difficult for me to remember when. The Ottavianos to a certain extent, though that has not always been an amicable relationship [Laughs]. Those were the (29:00) originals, and the tenants who lived next door.

DS: Next door?

LR: Who lived next door. I mean, they were really lovely. They were fairly transient, but they were all charming people. There was an elderly African-American woman who lived on the first floor for a while, and she always was –

DS: What address would this have been? 230 [Delancey Street]?

LR: Yes. Sure. That was, as I say, a tenement, in which a man came – a white gentleman came in his old, beat-up truck – and collected their rent every week. She lived on the first floor, and she was always looking out the window, and you felt very safe, because she was very aware. There was a young man there who used (30:00) to help us move stuff in, you know, help us around, in terms of moving stuff, because Franklin can’t lift stuff. We had a very good relationship with them. They were charming. Everything was empty up until then. You, of course, remember the house boarded up by our concerned neighbors, the house at 228 Delancey Street, which was a store front.

DS: 228?

LR: I don’t mean 228 – 218 Delancey, which was a store front. When our children were young, somehow that glass got broken and Joan Putney – by then Delancey Mews was built and Joan Putney was very much here – and all of us boarded that up, because we called the city a million times to get it [done]. We were afraid (31:00) the kids would get cut with the broken glass, to say nothing of somebody getting in that store. Yes, we boarded it up as concerned mothers. We then painted on the plywood that we’d boarded it up. Other stories: well, as I say, the birthday parties with pony rides on the empty field.

DS: The empty field was between – it was in the 100 block of Delancey?

LR: Between Spruce and Delancey [and Front and Second Streets], which we now call Attica East. It got its name, because there were a number of us who did not feel it was the most architecturally exciting block that was built, and it was at the time of the Attica riots. [Laughs] …. When Newmarket started, that was an issue that was very interesting too. Van Arkel and Moss (32:00) won the [Newmarket design competition], with a design which included townhouses and an ice skating rink and a few stores.

DS: Newmarket is between Front and Second, Pine and Lombard Streets?

LR: Yes…. The next thing we knew, with the interesting corruption that goes on in the city, the investors, the banks or whoever it was who had backed them on the competition, said, “No, we’re not building any townhouses. We’re not doing anything. We’re going to put a market there with restaurants and stores and so forth and so on.” Of course, we know that (33:00) didn’t work, because there was this naïve belief that all of these young people moving into Society Hill were somewhat like suburbanites in Gladwyne, etc., Chestnut Hill, and therefore would buy at upscale stores instead of going to Strawbridge’s, which is what we all did. [Laughs] Therefore, there was no market for the stores that went into Newmarket. There was a wonderful restaurant called the Rusty Scupper, which we all enjoyed, and it was a lot of fun, and there was the Benny Ha Ha, or whatever it was called, the Japanese restaurant. The upscale stores soon disappeared, because of course they couldn’t make any money, and there was no parking around there, and it had been sold. Van Arkel and Moss convinced everyone that it was going to be Ghirardelli Square, and that’s why it was all this glass construction like (34:00) Ghirardelli Square in San Francisco. Ghirardelli Square in San Francisco is surrounded by wide streets and tons of parking, and it is on the waterfront, which is called [San Francisco Bay], very different from the Delaware River. [Laughs] Therefore, to make the analogy that this construction would be that is absolutely absurd. We have unfortunately seen that that is true. Of course, after the upscales left, then it went into tourist junk, and again no parking, no reason to go there. It was not a beautiful view of [San Francisco Bay]. It was not an exciting venue. We [still] have an empty lot which hopefully will stay low rise, because this end of Society Hill is residential, low-rise, not a big city. (35:00) It is a small town.

DS: Tell me. Were you involved in the Crosstown Expressway?

LR: Oh, yes, against it, of course. Yes, the Crosstown Expressway, along with I-95, but the Crosstown Expressway, one of [Ed] Bacon’s unfortunate dreams, to ghettoize Society Hill. A number of us got together and really fought that vociferously. We were quite successful. [sound of telephone ringing]

[Tape is turned off, then on again]

LR: We worked, and that was effective. I mean, we made people see that (36:00) you do not cut a city in half. The Vine Street Expressway cuts the city in half, but it cuts a different part of the city, which was much more commercial.

DS: Tell me about your involvement with the civic associations.

LR: Well, Frank was the president of the [Society Hill] Civic Association. I was busy doing public education. My advocacy was both in political and in McCall’s School and public education in general. During the strike of ’72, I helped fund – found, not fund – the Parents Union for Public Schools, so I was always active in that area and not particularly the specifics of the Civic Association, other than to support the Section 8 [Benezet Court] issues that created such a schism in the Civic Association. Obviously, I (37:00) was supportive of having Section 8 housing. That needed to be. So were you. [Laughs]

DS: Yes, we were, very much so.

LR: Right. Franklin was president of the Civic Association. In fact, when Three Bears Park was developed, that was –

DS: Now, we’re talking what year? Do you remember?

LR: No, of course I don’t. Don’t you remember?

DS: Was he the first president?

LR: No, he was the second or third. You may recall, there was the old neighbors’ civic association. I forget what its name was. The new neighbors did not precisely feel that we had aligned interests with the old neighbors’ civic association, and so we formed a new one. There were two civic associations, and the other one (38:00) eventually died out with the neighbors. [Laughs] I’m trying to remember if Bill Eiman was the first president of the new civic association. I honestly can’t remember. Franklin was second or third.

DS: During Franklin’s time was when Three Bears Park was –

LR: That’s right. We got Three Bears Park; the city gave it to us. The iron mongers had moved out. It was just empty.

DS: Wasn’t there a fire station there? Or a police station?

LR: Um hum. It was just the iron mongers.

DS: Not when you came. What do you mean by iron mongers?

LR: People who did iron work.

DS: They had a factory?

LR: A forge. There was the hospital, Metropolitan Hospital, right on Spruce and Third. As you remember, we could play in Three Bears Park and watch the corpses coming out of the mortuary. (39:00)

DS: That door?

LR: At the hospital.

DS: Whose idea was it to get this property – to get the city to put this into a park?

LR: I don’t remember, and maybe Franklin can tell you, because that was his thing, was Three Bears. I think probably there was a group, because the three bears – the design of the actual sculptures – I don’t think that was Franklin’s decision. I’m sure there was a committee or something that developed that and commissioned the sculpture which gave it its name. Our kids also – Old Pine Community Center – oh, that’s the other thing we haven’t talked about, the gardens. Bertha’s garden, which is no longer – which was Nancy Grace’s house. At the head of Delancey Street, Fourth and Delancey, (40:00) was an open space, and Bertha von Moschzisker had started a vegetable and raspberry garden there. Wonderful raspberries and we all had that area. Then when somebody constructed a house there – I don’t know if Nancy’s was the first house – but anyway, when that garden disappeared, we had a garden, a wonderful vegetable garden at the corner of Fourth and Lombard, and that became the Old Pine Community Center. [Laughs] Until it was the Old Pine Community Center, we all had our vegetables there; we grew vegetables there.

DS: Did your children go to – where did your children go to school?

LR: McCall’s. That was why I was very involved in – well, I was involved in education before then – but became seriously involved, because Andy’s (41:00) first-grade year, which was also somebody’s named Greg Stevens’s first-grade year, was the historically long strike, 1972, with the wonderful Mayor Frank Rizzo. That historically long strike [was] when I helped start the Parents Union for Public Schools. It was very tough on the kids who were at McCall’s. We had emergency school with Joan Putney, and a number of [other] people put emergency schools together for [the kids], but they had been looking forward to being in the first grade. Until then our kids had gone to Montessori school. Laura, of course, [was] too young. The Montessori school that the Denworths [Joanne and Ray], ourselves, the Schwartzes [Harry and Marinda], I’m trying to think of who else – a number of us. The kids went to that Montessori school for preschool and kindergarten, then Andy went to McCall’s which was really tough, (42:00) because his whole first grade year –.

DS: Even after the strike you stayed there?

LR: Yes, after the strike I stayed there, and we had two or three more strikes, and then eventually, in the fifth, sixth grade, I switched him out to private school. He was really tired of strikes. What was interesting was those of us – there were a number of us citywide – who were real advocates for public education. At the time, when we had to make the decision, we had choices. Unfortunately, other students, other parents, did not have choices. It was very difficult for us to move our kids to private school, because we felt we were betraying our principles; (43:00) we had to put our kids first. We agonized.

[Tape is turned off, then on again]

LR: Yes, 237 Delancey, next to the Eimans, was the American Legion. They used to have Polish weddings, which went on quite a while, and became something of a joke in the neighborhood, except they were very noisy. It’s interesting that that structure was taken down and [Jim] Kise designed the house that was built there. Somehow the structure seems – other than the obvious modern design – somewhat the same, because it was a long, brick building with people pouring in and out of it all the time, [Laughs] and very noisy. It’s interesting to see that they sort of – they didn’t save the façade – but it’s the same idea and the same size as the structure of the American Legion that was there.

DS: Do you remember when the Legion was torn down? The 60s? (44:00)

LR: No. Well, it’s when Jim [Kise] bought the property. It was a Legion until they left, because their constituency was not in the neighborhood any more. They must have sold the property to Jim. It was not anything that went through the city. Whenever Jim Kise built that house – I don’t know if you have the same problem, when you’ve been in a space a long time and in the same place, things sort of telescope, so that you really have difficulty pinpointing a year that something happened.

DS: Yes, true.

[Tape is turned off, then on again.]

LR: I always think it was later – when our kids were born, and I guess that (45:00) was early for some people, because Andy was ’66 and Greg was ’66.

DS: Christopher was ’64.

LR: ‘64. We had play groups that we formed for Greg and Andy, because they were contemporaries, and it would give us time off. Joan Putney and Winnie Glockner and Dottie Stevens and our respective sons would trade off two or three days a week in play group.

DS: There was Joanna Putney.

LR: Yes, Joanna, of course. It was very interesting, because Joan was wonderfully creative in what she did with the children, and I would sit up on the fourth floor and just count the moments until they all went home. [Laughs] It wasn’t working. Then we had – and that was a real life-saver for all of us – we formed – and I guess – was (46:00) Joan the initial person who started that?

DS: Um hum.

LR: A co-op babysitting service that was truly amazing. When I talk to the parents today who are complaining about baby sitters and I say, “A co-op babysitting service.” They are appalled. They would rather pay babysitters, because they are a totally different group than what we were, in terms of ability today, than be bothered trying to do all the arrangements. Peggy Davies kept the book, and we worked very effectively. We traded off hours. It was wonderful on New Year’s Eve if somebody was staying home, and we would have these children all around. One of the very special parts of that time in the neighborhood was that it was truly extended families. Your child would go to almost – they knew every house in the neighborhood, whose mother was home, or (47:00) whose father or whatever. They knew there could go there at any time.

[End of side one of the tape; side two of the tape]

LR: It was just a very close-knit group. I mean, parents might not see each other separately that much socially. They usually did. Our friends were our neighbors. It was much easier on a Saturday night to walk to somebody’s house for dinner than to get in a car and go someplace. We really, while our children were young, we really socially interacted primarily with our neighbors and occasionally with suburban friends. There were always July 4 th parties, Christmas parties, everyone had Christmas parties, or just dinner exchanges, and to go to the movies. We’d work with the co-op babysitting service. That made it possible, because your kids were comfortable going to other people’s houses or having them come here, depending on whose child needed to be in bed when, because they knew (1:00) everyone so well. It was just a very good time to raise kids in the middle of the city. It’s true our kids lost their bikes regularly [Laughs]. We had taught them all, your bike is worth less than your life, so give it up…. That’s the way. That happened with a certain amount of regularity. There were some disadvantages from that perspective growing up in the city, except it taught our kids what the world can be like, and not everyone has the advantages that you do, and you have to deal with that kind of stuff. At the same time, they grew up in a neighborhood that was really very protective of them and provided them with those kinds of exposures and those kinds of opportunities to see what (2:00) it’s like to live in an extended family.

DS: Tell me about the block parties.

LR: The block parties again, we started –

DS: This was just the 200 block of Delancey?

LR: It was the 200 block of Delancey. Barbara Leff, actually, I think it was Barbara Leff, and I’m sure it was Joan Putney, because that would be the Joan Putney kind of thing, began block parties where we would close off the block. The 100 block of Delancey was always welcome, as were the few people we knew in the 300 block, though we didn’t know many. We had the firemen come; the fire engines came, always for the children. We would close the street, put the food out, and we had them annually for years, until our children grew up, and the neighborhood changed. The neighborhood changed, because we could not imagine that people with young (3:00) children could afford to live here. The prices have changed so while we were raising our kids, and for a while that was true. Suddenly I don’t know where these kids all got their money, but the prices were out of sight and we’re surrounded by just as many, if not more, people with young children than we were when we started out.

[Tape is turned off, then on again]

LR: One of the things we haven’t talked about is one of the less positive aspects of the development of the area: the speculators who bought up a number of the houses and a number of the lots. Because of political connections, they were able to build houses that were not architecturally up to what we would hope the (4:00) neighborhood would look like with contemporary houses. They also treated the rest of us fairly badly in terms of their construction debris and parking. Again, we’re not architecturally superior to the 18 th century. One of the things we did have in our neighborhood were Martin and Hannah Pyle, who were very serious restorationists. When we tried to build our contemporary house, they were at us every minute of the day. “What are you doing now? What kind of construction are you doing?” They believed that the 20 th century should recreate the 18 th. We believe that you should save the 18 th and (7:00) restore them, but that the 20 th century should build 20 th century houses. The Delancey Mews houses, which is where the gas station was, I would not object to those. I certainly object to some of the contemporary attachments, or accommodations to 18 th century houses, such as the monstrosity next to the Barclay House, which took a beautiful Japanese garden and did something very strange to it. [Laughs] But it was interesting in the early days with the speculators, who would hold onto houses (8:00) that people would like to do themselves, because they were waiting for the higher price. And in some ways that held back the neighborhood.

We didn’t talk about I-95 much…. When I-95 was under construction, Andy Roberts and Kert Davies used to play down there along with John Stevens regularly. They brought home a series of kittens that were apparently abandoned down there, which became very much a part of the neighborhood families. I-95, as I’m sure you’ve heard from others, and I mentioned earlier (5:00) how we started fighting it. Stanhope [Browne] and Martha Shober really led that fight, and did it very effectively. Jan Mears has pointed out that the elevation would separate Society Hill from the riverfront….

DS: Yes, there did seem to be a lot of architects and historians and restorationists living in the neighborhood.

LR: Yes, and that was wonderful.

DS: Yes, the Nicholsons [Arnold and Elizabeth] were another family like the Pyles.

LR: Right, but the Nicholsons did not object when we built a contemporary. Arnold and Elizabeth [Nicholson] were friends of ours. Hannah and Martin Pyle were difficult to be friends with, because there was a certain rigidity there, and they felt they were the police of the neighborhood in terms of historical accuracy. (9:00) Whereas, if Elizabeth and Arnold felt any problem with our building the house, they certainly kept it quiet and [Laughs] did not share it with us.

However, that does bring up a funny story. There was a summer party with the Nicholsons, and I don’t care for shoes. Another of our old neighbors, Joan Putney, also did not care for shoes. We were at the party, and I wanted to come back and check on the kids. Since it was a brick sidewalk on their entryway and in their garden, I of course had no shoes on, because I could not wear heels on the brick sidewalk [without falling]. As I was doing this – and this was one of the things we haven’t addressed – there were often tourists coming through the neighborhood (10:00) who would peer into your front window without any embarrassment at all, and stare at your house. That happened as I was returning to check the kids. A group of tourists came up and looked horrified at this woman, fairly well dressed, but with bare feet, walking down the sidewalk on a summer afternoon. I smiled at them and said, “Everybody in Society Hill goes barefoot.” At which point, Joan Putney was walking – barefoot – up the other side of the street, with her dog Kehoe. I turned. “See,” I said. “There we are.” [Laughs]

[End of interview]

© 2008 Project Philadelphia 19106™. All rights reserved.

Lynne Roberts

Dorothy Stevens

228-230 Delancey Street

Cynthia J. Eiseman

222 Delancey Street

Cynthia J. Eiseman

228-230 Delancey Street

Cynthia J. Eiseman

228-230 Delancey Street

Mitchell/Giurgola Architects

228-230 Delancey Street - 2nd and 3rd floor plans

Mitchell/Giurgola Architects

228-230 Delancey Street - Cellar and 1st floor plans

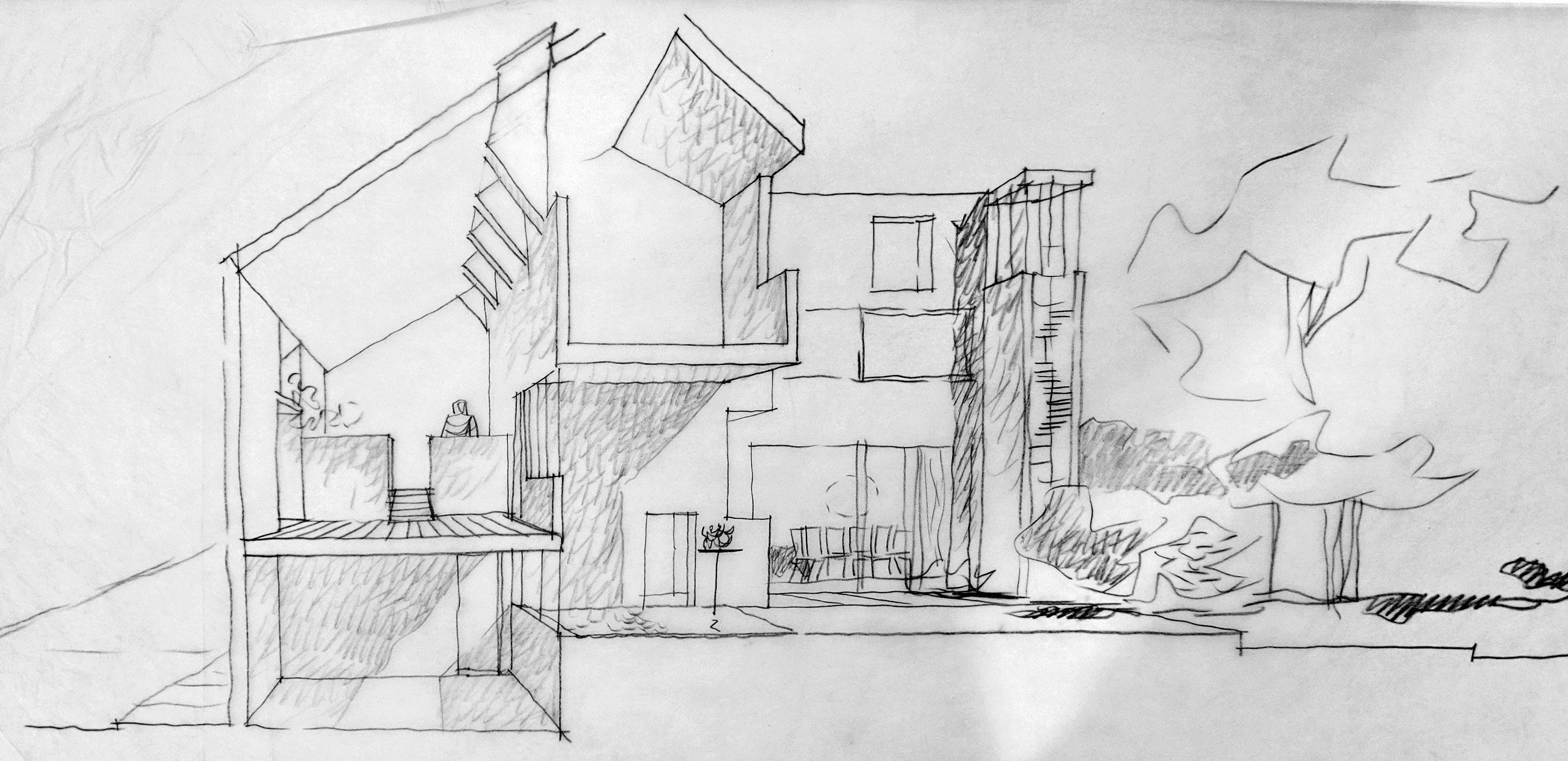

Romaldo Giurgola

228-230 Delancey Street - Schematic backyard plan

Romaldo Giurgola

228-230 Delancey Street - Schematic interior perspective

Romaldo Giurgola

228-230 Delancey Street - Schematic section

Romaldo Giurgola

228-230 Delancey Street - Alternate schematic elevation