Penny (1928-2007) and George (1927-2009) Batcheler were both architects with an appreciation for historic houses in Philadelphia. They bought and restored 315 S American Street for themselves and then restored 314 for Penny’s mother. They provide a history of the street. Around 1846, ten houses (“identical but bookmatched”) were built, five on each side of the street. The Batchelers describe various features of the houses and explain how they worked or benefitted the residents: e.g., heating systems, louvered interior doors with sidelights, the location of front doors, side alleys, fireplaces and chimneys in relation to one another. They also provide references to source materials. The house at 314 preserved more original details. The authors list several procedures that the Redevelopment Authority recommended they do as part of the restoration. The Batchelers interpreted these as boilerplate suggestions for all historic houses and chose not to comply with them, thus preserving several unique and important features. They tell a story about how they came into possession of a marble mantel, hearth, hearth bricks, and a set of iron fire back and jambs to use in 314. In this tale, they use such terms as “accomplice,” “rescue,” “Sunday morning about 6 a.m.” and “removed plywood from a back window.” Such activities were widespread during redevelopment and served to recycle many fine architectural elements that would otherwise end up in a landfill.

When did you come to Society Hill?

Penny moved into 238-B Delancey Street (Drinker’s Court) as a tenant of Elizabeth and L. Arnold Nicholson, on October 18, 1964. George moved in when we were married, February 9, 1968. Looking for a house to restore, we spotted a 3x5 card advertisement with just a phone number, nothing else, in the window of 315 S American Street, a quiet, one-way, narrow street paved in Belgian block.

Why did you come to Society Hill?

Penny had worked at Independence National Historical Park since November 1955 as a Historical Architect and knew the old houses of Society Hill, having surveyed them to learn about 18 th century Philadelphia domestic architecture. This background helped with the restoration of the Bishop White and Todd houses at the Park. From 1959 on, Charles E. Peterson was Penny’s boss, and he introduced her to the Nicholsons, who eventually invited her to be their tenant in one of their ca. 1765 courtyard houses. George was an architect with the firm at that time called Kneedler Mirick & Zantzinger. He had been introduced to old houses by having lived on Elfreth’s Alley.

History of American Street:

American Street has had three different names. It started as Ashland Street ca. 1846. The first listing of Ashland Street is in McElroy’s Philadelphia Directory of 1847, [page] 401. See this name carved in the marble plaque in the side wall of 227 Delancey Street. The name was changed to Aberdeen Street, which is listed in McElroy’s Directory of 1859, [page] 923. South American Street was the next name, changed ca. 1900, as shown in Gopsill’s Directory of 1900, [page] 48.

The north end of the present American Street was laid out as a cul de sac ca. 1811, leading south into the block from Spruce Street, and called Towsend’s Court. In 1846, two adjacent properties, 47 and 49 Union (Delancey) Street, owned by a soapmaker James Fearon, were sold to William and Francis Carpenter, merchant tailors (see McElroy’s Directory for 1841, [pages] 83 and 41), who very soon arranged to have Ashland Street put through northward to Join Towsend’s Court. They then began the development of ten houses, five on each side of the street (311-320).

The ten S American Street houses are identical yet bookmatched. As the slope of the street rises northward, the houses jump slightly upward. They have three stories with two rooms per floor. Originally their kitchens were in the rear cellar with open fireplaces and cranes, and brick furnaces were in the front cellars with a brick smoke flue and brick hot air ducts heating the first and second floor front and rear rooms. The third-floor front and rear rooms were heated with small mantled fireplaces. There were brick privies in the back yards, their pits shared by the adjacent houses. Above the privies there were “Frame Bath Rooms” with cold water to the tubs. Open neweled stairs rose from the first to third floor. Louvered doors separated vestibules from the stair halls. Back doors with sidelights led outside to the brick privies. Two and one-half foot wide alleys are still shared by adjacent houses, providing direct access to the rear yards.

As with most old Philadelphia row houses, the front doors and hallways of the American Street houses are placed on one side of the house, and the chimneys and fireplaces are against the opposite side of the houses. This brought up a curious situation. Because the alleyways are also placed opposite the entrance doors, they had to coincide with the chimneys. Having hot air heat ducts made this combination lighter, as the chimneys did not have to be so massive; they also had decorative niches to further displace the masonry mass. The chimneys of adjacent houses rise on each side of the alleys, and above the alleys the upper floor chimneys come together back to back. The chimneys and their party wall bear on wood timbers which span across above the alleys. This has worked for all these many years, but today The Philadelphia Contributionship insurance company looks askance at such construction and would not issue a policy for 314 or 315 S American Street.

More specific descriptions of the S American Street houses can be found in the fire insurance surveys on file at the Philadelphia Historical Commission office: for 315, ca. 1846 Philadelphia Contributionship, policy 13189 and policy 11253 of March 31, 1868. The policy number for 314 is 11252 of March 31, 1868. They include diagrammatic floor plans.

In 1991 a paper [w]as written by Natica T. Schmeder for Roger Moss’s class “Mechanical Systems of Historic Buildings,” University of Pennsylvania, entitled “Evolution of the Mechanical Systems of 315 South American Street, Philadelphia. Ms. Schmeder was an intern working in Penny’s Park Service office. This paper gives even more information about the houses.

Record photographs were taken ca. 1959 of both exteriors and interiors of the Society Hill houses. On file at the Historical Commission, these were very helpful in researching missing details. City Hall negative 43821 was taken in 1908 and shows the American Street houses with fire escapes on the fronts, providing safety for the apartments then on the upper floors.

Today, because the Historical Commission has no jurisdiction over the interior treatment of certified houses, the ten houses on American Street which started out in 1846-47 as almost identical are now similar on the exterior and entirely different on the interiors. Two have been completely gutted, and the rest have varying amounts of original detail left.

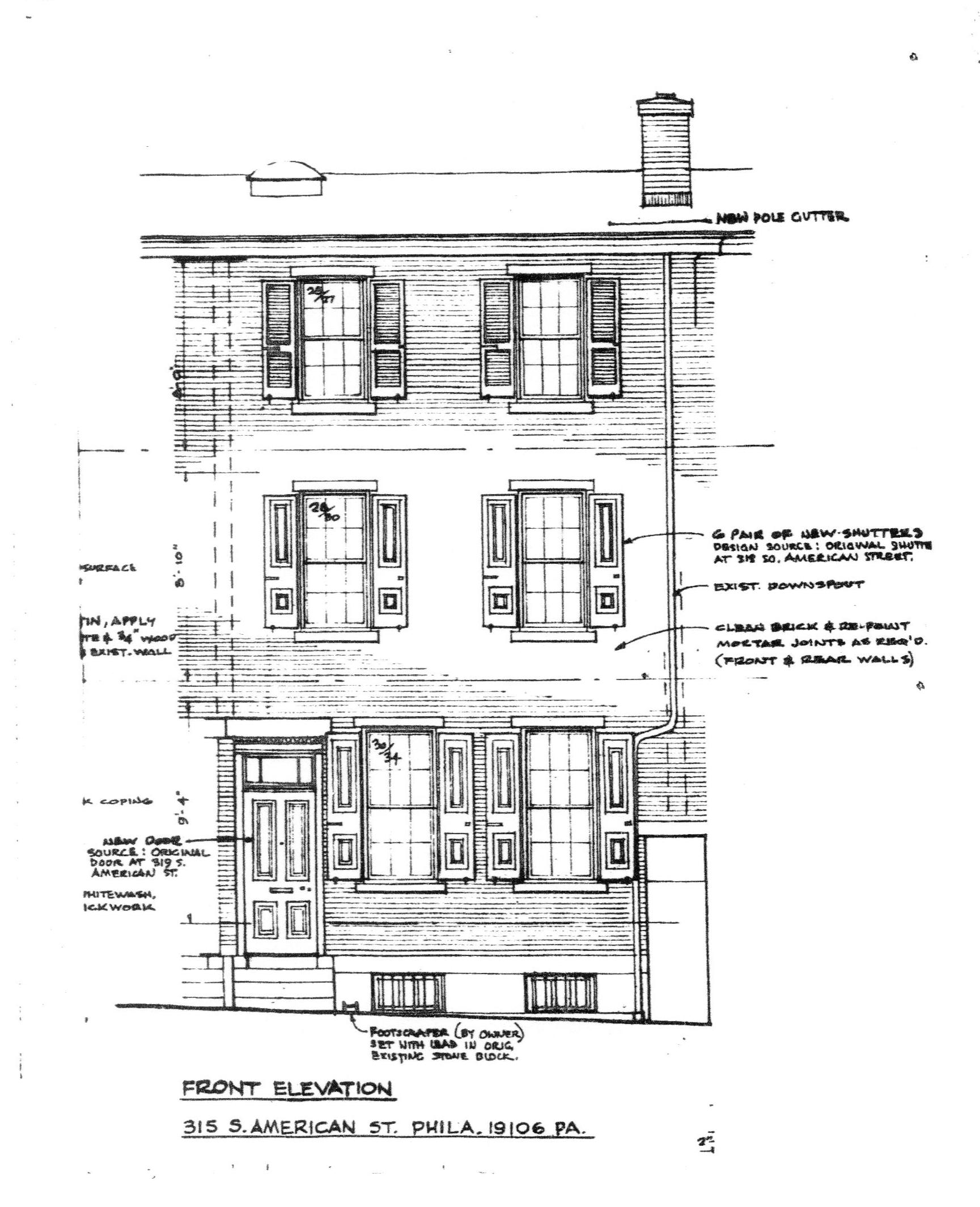

The exteriors of all the houses have met the Redevelopment Authority specifications with reconstructed shutters and front doors. Many of the owners have added gardening boxes below the first-floor windows, a detail unheard of in the mid-19 th century. Hand rails have been added at some of the marble front steps, providing safety. Lighting fixtures have been added near most of the front doorways to bring security to the street.

The interiors clearly vary according to the wishes of the developer owners. Some of the details were already missing when the 1959 record photographs were taken. This is all understandable, as styles of living have changed over the years.

Independence National Historical Park has a collection of architectural artifacts which contains a number of original items from the S American Street houses salvaged from dumpsters or found in 315 and 314 as they were being restored.

315 S American Street

Condition of property at purchase: We purchased 315 S American Street on April 9, 1968. No one had lived in the house for a number of years, but they had left old furniture, bath and kitchen fixtures, wallpaper, and a huge gong at the third-floor level, probably dating from the period when the house had several apartments. The paint on the wood trim was thick and hid the moulding details. The plaster ceilings had many uneven layers of whitewash. The floors were covered with linoleum. The utility systems were not to be trusted, nor was the roof.

Did you restore your house or did someone else restore it? If others, who? What do you know about them?

As we both were architects, we designed the restoration of 315 S American Street, and Contractor Carl Peterson was chosen to do the restoration work.

What were the Redevelopment Authority’s specifications governing the restoration of your house?

Neither we nor the Historical Commission file on this house has a copy of the Redevelopment Authority’s specifications. On January 6, 1961, the City Department of Licenses and Inspections filed a Complaint for 315 S American Street, which said in handwriting, “I have inspected the above property and found building to be structurally sound at this time. Building is in need of extensive repairs to be restored.” This seems to have been the standard report for most of the houses inspected, unless there was clearly some major deficiency. On July 25, 1968, a letter was sent to us signed by Roy Franklin Nichols, Chairman of the Commission, saying, “Your submission for alterations and restoration of this certified building is approved. The drawings are excellent.” Copies were sent to the Redevelopment Authority Advisory Architect John Lloyd, Architect Erling H. Pedersen as a member of the RDA Advisory Board of Design, Mrs. Jared Ingersoll who chaired the Old Philadelphia Development Corporation Historic House Committee and Mae Belle Segel who was RDA Project Administrator. Teamwork was part of the process.

On July 19, 1968, we were given a Building Permit, to be posted on the house in clear view from the street, allowing “partial Demolition only” and to include a “New front door, shutters on front windows, bath on 2 nd Fl. rear [the original bath room] & 3 rd floor, restore rear wing wall & make fire resistive. Add framing in rear wing & 3 rd floor, new skylight, roof deck [atop rear wing], plumbing, heating, electric.”

What stories can you relate about experiences you had when restoring your house? With the Redevelopment Authority or other city agencies? With contractors or suppliers? Banks or other lenders? With neighbors who were also restoring houses (or not restoring them)? With neighborhood associations? Others?

Penny, having worked with 18 th century architecture, was not at all sure about the architectural vocabulary of the 1840s, nor was she sure she was going to enjoy living with this later period. All it took to win her was to study the building. For such modest houses, there was a distinct hierarchy between the treatment of different floors. The trim at the windows and doors, the door paneling, and the hardware types varied: the most elaborate and up to date at the first floor; less elaborate but up to date at the second floor; and at the third-floor throw-backs to an earlier period. The stair was completely original, and the plaster cornices at the first floor were mostly intact. For such relatively small houses. The ceilings were high and the windows were large, bringing in lots of light, even when it was reflected from the other side of the street. The house was, as were its neighbors, surprisingly sophisticated. Indeed, their architectural details, particularly the interior door paneling, match those of the Philadelphia Athenaeum, designed by John Nottman in 1845.

In checking out everything, we crawled into the loft space under the roof rafters and found the following articles: a broken blown-glass baby nursing bottle, an old wallpaper-covered hat box, a small rag doll, and a small wood hobby horse with wheels at the floor end.

At 311 there was an original louvered vestibule door to be opened, and other missing details showed up in some of the other houses.

George had the knack of laying out rooms of good proportions and of maneuvering utilities so that they are hidden yet functional. Penny was in charge of the architectural detailing. Fortunately, the foreman on the job was a carpenter of knowledge and skill, Jack North from Portsmouth, England, with a stub of a pipe clenched in his teeth. He understood what we wanted and met our wishes, only to have the Contractor say, “Hey, I didn’t contract for all these dutchmen!” i.e., beautifully patched woodwork.

Carl Pederson was a good contractor. He said he could do the job in five months, and he did a good job in six and one-half months. The last entry in our log starts, “There were 12 workmen on the job—2 floormen, 2 electricians, 2 plumbers, 3 masons in the backyard grading and mending the areaway walls, 2 carpenters and Carl Pederson…”

On March 3, 1970, the log reads, “It’s been almost a year of increasing enjoyment in the house. The floors turned out to be beautiful—and with an added coat of wax they glow warmly. The Independence Hall Quill Finnaren & Haley paint color on the trim is marvelous.”

Do you have photographs of your house before, during and/or after restoration? Other interesting documents related to its restoration or its earlier history (e.g., the original builder, previous owners, etc.)?

We have before, during and after photographs (black and white, square format).

Society Hill resident Ann Koss has told us that, from 1930 to 1933, when she was first married, she lived on the third floor of 315, above her in-laws.

Natica T. Schmeder, for her paper on the mid-19 th century mechanical systems of the American Street houses, found that the first tenants on the street were middle-class shopkeepers or clerks. In the late 19 th century, in 315, there was an upholsterer and family as the tenants. In the early 20 th century, 315 was a three-family house with a Russian tailor and family of five children having the cellar kitchen and the first floor, an Austrian/Polish peddler and family of four children on the second floor, and on the third floor a Russian couple, he working as a “partsmaker”.

314 S American Street

Condition of property at purchase:

In 1972, we happened to see in the obituaries that the owner of this property had died; he was the same owner from whom we had purchased 315. A phone call to his widow started negotiations. The owner had held 315 and 314 from 1937 and 1940, having rented apartments on each floor. The condition of 314 was considerably worse than at 315. There were large padlock hasps at each door, and on the windows were three-penny nails that had once supported window shades or curtains. The doors and trim had split or at least had large holes disfiguring them. The hallway of the first floor was painted dark brown to waist height, and the rooms had dark red imitation flock wallpaper and were filled with discarded furniture such that a great nephew, age 7, burst out, “This is glo-o-o-my!”

To maintain his apartments the owner collected any item that could possibly be useful and handy. He had in the cellar the greatest collection of bent nails and old screws, pipe lengths, door knobs and old faucets, as well as old doors and what proved to be an original paneled shutter. When working on 315, the owner gave us the very large paneled doors from 314 that had separated the two first-floor rooms. We had a difficult time getting them out of the house.

There were surviving original details in this house. All the chimney breasts with niches remained, as well as the third-floor fireplaces. The stair was intact, most of the paneled doors survived with original hardware here and there. The prize was the original louvered door and its hardware at the vestibule. All of this detail was obscured by many layers of paint. The plaster surfaces had been abused throughout.

Did you restore your house or did someone else restore it? If others, who? What do you know about them?

As with 314, we were the architects, restoring the house for Penny’s mother to enjoy. Having dealt with 315 first and having a knowledge of Mrs. Hartshorne’s life story and furniture made the planning process easier. Our relationship with our contractor, however, was a more strenuous situation with 314. This may have been due to a number of things. We lived across the street from the job. We knew the house inside and out, and knew exactly what we wanted. The project was larger and more complicated, and the contractor was not as well organized as was the man of our prior experience.

What were the Redevelopment Authority’s specifications governing the restoration of your house?

The RDA specifications seem to have been written en mass, and fortunately we did not follow them to the “T”. The particular task asking us to “repoint entire front” would have undone the narrow mortar joints that were achieved from the use of machine-made bricks with their precise edges, having a different character compared to 18 th century hand-made bricks with wider joints.

The RDA asked for the demolition of the privies and frame bath rooms. Having preserved these structures, as we determined them to be original at 315, one would expect the same at 314. Our program was different, however. We needed that space for a larger addition to the house. We needed to provide a first-floor kitchen and a bedroom above. This was possible because the RDA had arranged that the houses on the west side of American Street should have additional land attached to their back yards, taken from a former hospital parking lot. There were some dimension technicalities in the design of the new rear addition that sent us to the Zoning Board of Approval. George appealed to the six members on behalf of his mother-in-law who, as a good cook, wanted a proper kitchen. There was not a dry eye among them, and we were given permission to proceed.

What stories can you relate about experiences you had when restoring your house? With the Redevelopment Authority or other city agencies? With contractors or suppliers? Banks or other lenders? With neighbors who were also restoring houses (or not restoring them)? With neighborhood associations? Others?

In repairing/restoring the trim of this house, we had to remove it from the walls. We took it along on vacation to New Hampshire, feeling that the job would be less onerous when done in glorious countryside. We were smiling and putting in dutchmen (patches), proud of our handiwork when George’s father turned to us and said, “I’ve burned better wood than that!” Once in place, primed and finish painted, the trim has regained its stature.

By 1973 the plans had jelled for the Vine Street expressway, and Penny was told of a house in its path that had a marble mantle that would be lost in demolition. Her mother had voiced an interest in having a working fireplace in the second-floor front room to be her library. On a Sunday morning about 6 a.m., Penny and an accomplice removed plywood from a back window of the N American Street house to examine the mantle. Despite pink paint on everything, the mantle, a marble hearth, square hearth bricks, and a set of iron fire-back and jambs had to be rescued. The 314 S American Street original chimney breast was changed from containing a hot-air duct to having an open fireplace, a departure from historic purity.

Do you have photographs of your house before, during and/or after restoration? Other interesting documents related to its restoration or its earlier history (e.g., the original builder, previous owners, etc.)?

We have photographs during and after restoration. One does not often find out who the craftsmen were in building a house, but on the door that originally led to the frame bath room, there was branded into its surface the name “A.B. OGDEN”. In McElroy’s Philadelphia Directory of 1846, Ogden was listed as a carpenter who lived at Schuylkill 8 th, above Race. He could not be found to be a member of the Carpenters’ Company.

A head-bolt that was on the large paneled doors that once separated the first-floor rooms (now at 315) was stamped “N. CUSTER PHILADA 18”. This is parallel to a lock marked “Schlage” today. In the 1846 McElroy Directory, a Nathan Custer had a black and whitesmith shop at 159 Poplar Street. At his death, his assets included his shop and over $23,000. We credit Natica T. Schmeder again for looking up Ogden and Custer in the directories.

© 2008 Project Philadelphia 19106TM. All rights reserved.

Penny Batcheler - headshot

Dorothy Stevens

315 S American Street

Cynthia J. Eiseman

315 S American Street

Penelope Batchelor

View of S American Street looking north from Delancey Street - before renewal

Robert C. Smith

Elevation drawing of 315 S American Street

Letter to George and Penelope Batcheler