Elizabeth Browne (known as Libby) grew up in Chestnut Hill, a northwestern Philadelphia neighborhood. The first time Libby saw Society Hill was in May 1964, when she went on a house tour of the neighborhood with her friend, Stanhope (Stan) Browne. Libby and Stan enjoyed the tour, but what really impressed them was the sample apartment in Society Hill Towers, which had just opened. In short order they became engaged, got married, and moved into an apartment in the West Tower.

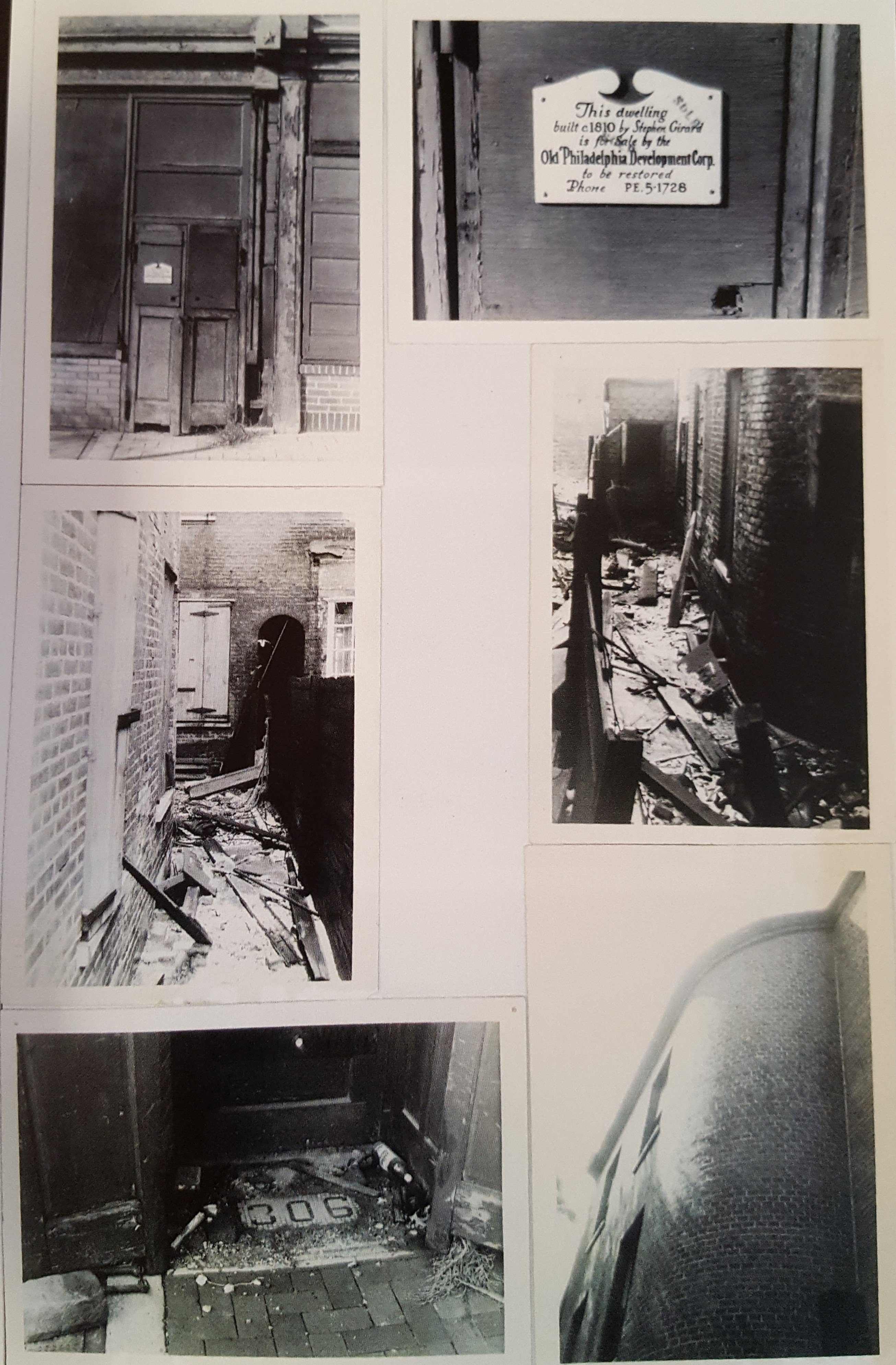

They knew a few people who were already living in Society Hill and fixing up derelict houses, and soon they got “the bug” to do so. They found 306 S. Second Street, one of three in a row built in 1816 by Stephen Girard. Its particular appeal was that it retained the most historic fabric and was in the best condition. Stan scraped paint; and Libby used the American Philosophical Society’s microfilms of Girard’s papers to prove the size and shape of the original first-floor window, which had long since been replaced by a storefront. The historical record was confirmed by a long-time resident of American Street, who had played on S. Second Street as a child and remembered that the house had one large window on the first floor.

Libby talks about bringing up children in the city and how easily her children took to city living.

Libby discusses the changes taking place in the neighborhood, with long-time residents moving away and newcomers arriving. The latter group had a big influence on neighborhood institutions, breathing new life into St. Peter’s School and the churches. Libby became active in the Friends of Independence National Historical Park, started Philadelphia Open House Tours, and as Chairman was in charge of the creation of Welcome Park at Second and Sansom Streets. Meanwhile, Stan got involved in issues affecting the region as well as the neighborhood, such as depressing and covering Interstate 95 where it passed Center City Philadelphia. He recounts this story in a separate personal narrative on this website.

Appended at the end of this oral history is a written history of 306 South 2nd Street. Combining archival and secondary source research with her own family’s personal experience in rehabilitating the house at, Libby Browne documents her Society Hill residence, from its construction in the early 19th century to the completion of restoration in 1979. Rody Davis served as architect for the restoration project. When complete, the house became home to Stanhope Browne, Libby Browne, and Katrina and Whitney Browne.

DS: This is an interview with Elizabeth Browne, affectionately called Libby. The address is 116 Delancey Street; the interviewer is Dorothy Stevens; the date is October 13, 2009.

[Tape is turned off, then on again]

DS: Libby, when did you and Stan [Stanhope Browne], or when did you, come to Society Hill?

EB: Stan and I came together for the first time I ever was in Society Hill. He had been looking around a little bit before [that], when Ted Newbold told us about a house tour that was happening in May of 1964. We had to be in town for another reason, so we decided to come and see this new neighborhood that we were beginning to hear things about. We loved the tour, but the thing we remembered most was (1:00) going to the sample apartment at Society Hill Towers, which had just opened and was part of the tour. At that time, Stan was living in Chestnut Hill and working in Center City as a lawyer; I was teaching at Springside School in Chestnut Hill, living with another teacher in a little house at Cliveden in Germantown. We [went] into that sample apartment and we were just blown away by the views of Center City and looking out at this historic neighborhood. It was just amazing. I said, “Gee, I could live here and have a reverse commute to Chestnut Hill with my roommate.” Stan said, “Boy, if I lived here, I could walk to work. Wouldn’t that be great?” So, that was very fine, and guess (2:00) what? We got engaged about a week later, and the first thing we decided was [that] we wanted to live in Society Hill. We signed up for an apartment, and we became the twelfth tenant in Society Hill Towers, in the West Tower, which was the only one complete by that time. We got married that September and came back from our honeymoon in October and moved right in to the Towers and fell in love with it. It was great to be living in that place.

DS: What then happened between the time when you lived in the Towers and when you bought your house?

EB: The nice thing about coming here was that we knew a few people. Stan knew Ted Newbold, and I knew Florry Lloyd and John [her husband]; Florry’s a distant cousin of mine. (3:00) They were very welcoming and quickly introduced us to lots of other people in the neighborhood. We got to know this group of young couples, young families that were restoring houses and really taking this big leap into this place, which, at that time in 1964, was still pretty derelict looking. People say it was a slum. It wasn’t a slum. It was just kind of empty, because so many people had moved out so the houses could be restored. We pretty quickly got the bug of restoring a house. Within a year, we decided we really liked living here and saw a great potential for the neighborhood. We started looking at all the houses and by the end of 1965, we had identified a house (4:00) that we wanted, but somebody got there first. Fortunately, they backed out, and we were able to get the house at 306 S. Second Street. It took a long time to decide. There were two or three others that we were trying to decide which would work best for us.

DS: Were they all around on Second Street, or were they more west?

EB: No, one was on the 200 block of Pine Street, and the other was at Fourth and Locust Streets.

DS: Where did Florry and John [Lloyd] live at that time?

EB: They lived on Philip Street in a little tiny house and Jack and Molly [their children], I think, were born by that time.

DS: You knew the Robertses?

EB: Through them [the Lloyds], we met the Robertses. Also, Lynne Roberts came from (5:00) Cincinnati, where my husband had lived for the last two years of high school, so she knew Stan’s sister. They went to the same school. We didn’t know they lived in Society Hill when we came, but we quickly met them and became very good friends.

DS: You got the house that you wanted. Was Ted Newbold showing you these houses?

EB: Yes.

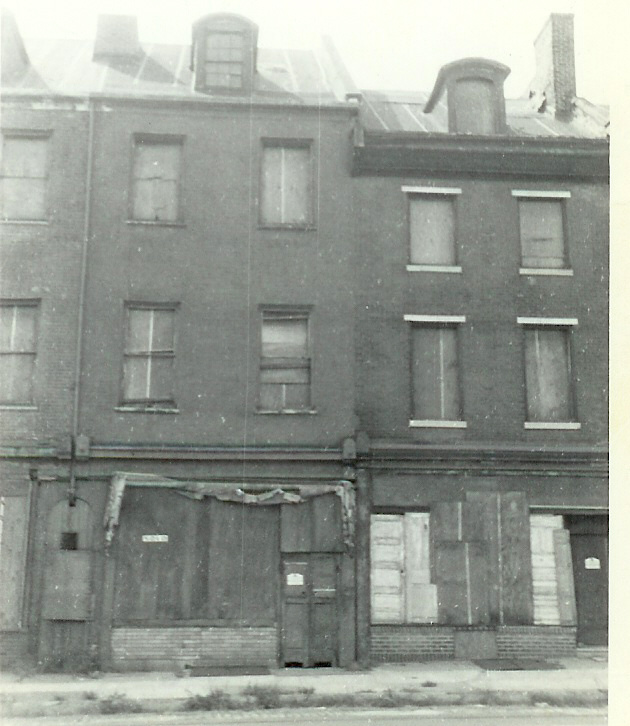

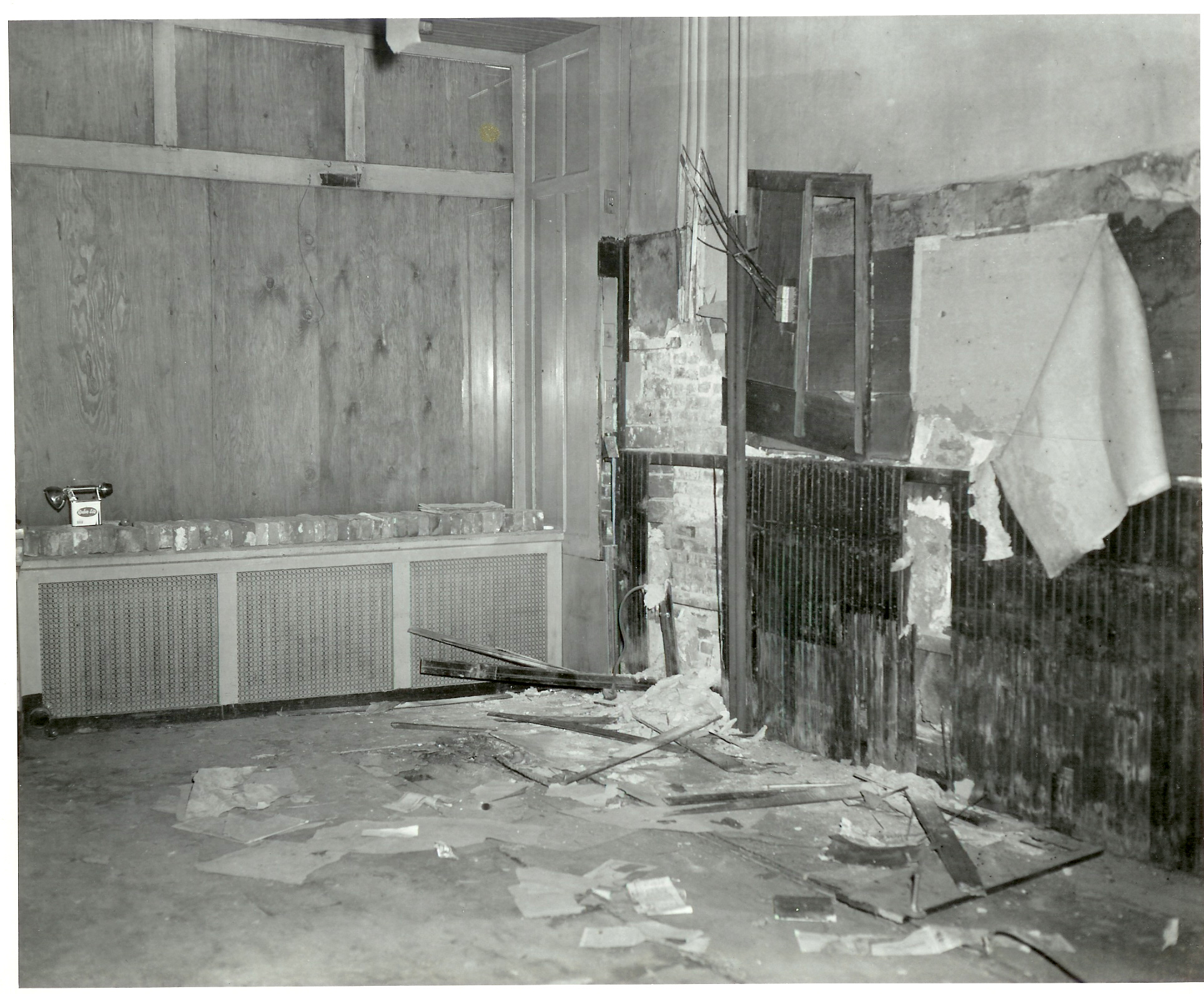

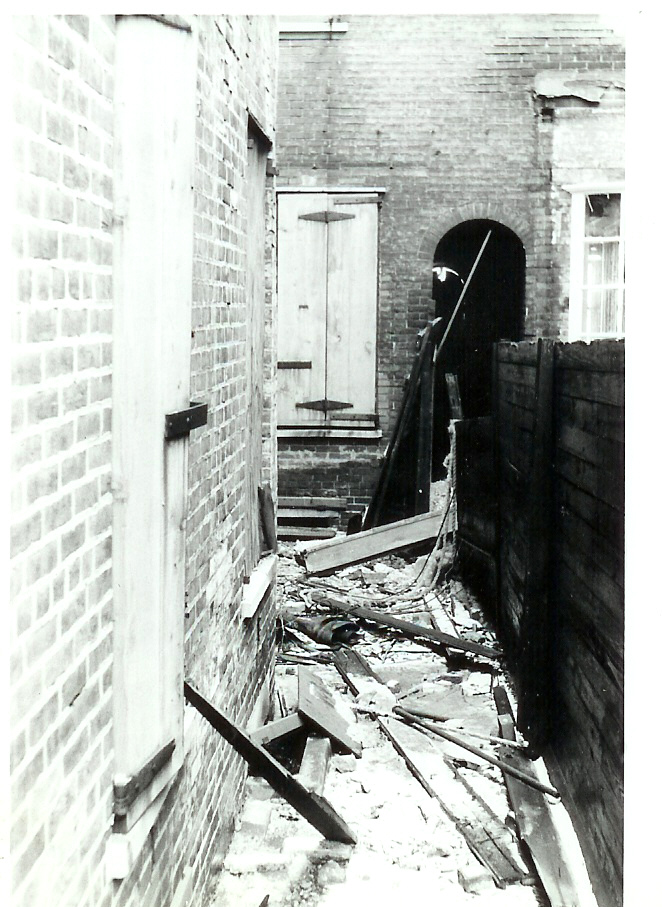

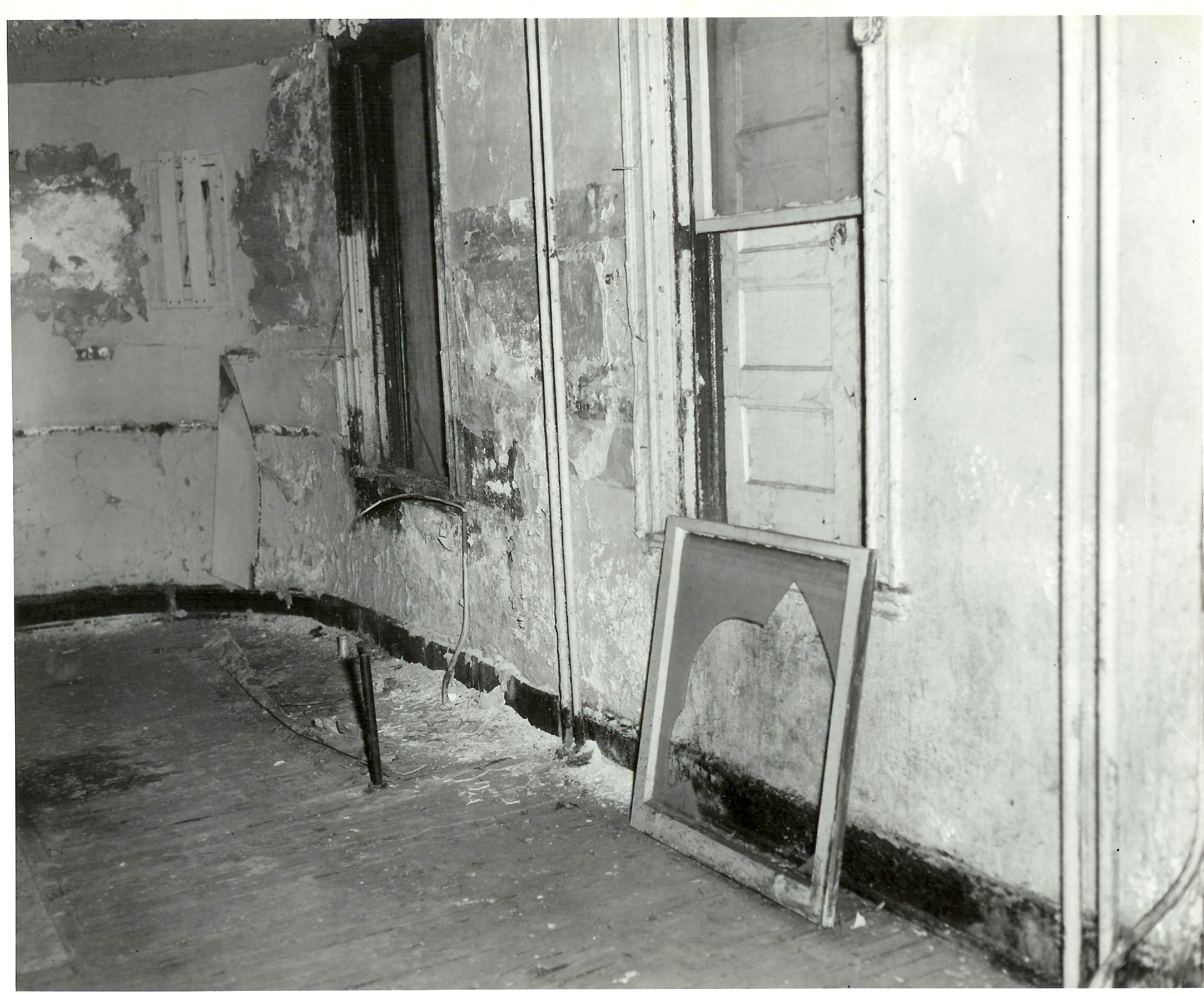

DS: Tell me about the condition of the house when you bought it.

EB: It hadn’t been lived in for seven years. It is one of three remaining houses in that row built by Stephen Girard. There were four to begin with, and one was torn down, to make way for the Delancey Mews development. Of the three remaining (6:00), ours was in the best condition and had the most original fabric in it. That’s one reason we really liked it. We had to put in all new systems. There was electricity in the house, but it probably dated to the 1920s or something.

DS: What is the date on the house?

EB: It’s 1816. We had a lot of work to do in terms of systems and replacing the storefront.

DS: It had been a –

EB: It had been a restaurant. We met someone whose in-laws owned the house. She said it was an all-night restaurant for the dock-workers and the market workers so that they could come in and get a meal at all hours. They (7:00 ) had, at some point, for the restaurant, lowered the ground floor to ground level, so to be historically correct, we had to raise that up, maybe 14”, something like that. That was probably the biggest single job that had to be done, apart from the systems. Otherwise, it was pretty much just cosmetic.

DS: It had bathrooms?

EB: No, no, it had all the plumbing, the heating, and the electric; that of course was major. We didn’t want to damage any of the historical fabric of the house. Rody Davies, who was our architect, came up with a heating system that was forced (8:00) hot air or cold air (well, it wasn’t cold air until a year or two later) from units in the ceiling, so that we didn’t damage the baseboards, which were original. It meant that each room could be individually controlled, which was a great idea, and I guess it worked well, but there were times when we wished we had a general system. It’s more efficient, because there are rooms that we never use, and we don’t have to heat them. It works pretty well.

DS: You have tall ceilings.

EB: Yes, yes.

DS: If the house was empty for seven years, were there animals or roof leaking, or…?

EB: I don’t remember big problems with that. It was pretty tight. The animal we had was a stray dog who – there were people in the house next door, just to the south, (9:00) Bernie and Pearl Kramer, who had already started restoring their house. They had found this stray dog named – oh, I used to remember the dog’s name, but that’s not really relevant – and she gave birth to a litter of puppies in a shed in the back of our house, because it was all kind of open between the houses at that point. There were no fences in between. They kept one of the puppies, Bingo, or something like that, and had that dog for a long time. They were really nice dogs. We didn’t find rats; there were always mice, but nothing drastic.

DS: You hired Rody [Davies]. Did you do any of the restoration yourself, or did you oversee it, or what?

EB: You know, Stan was inspired by all his new friends who were scraping (10:00) many coats of paint off the woodwork in their houses. The major work was done by a contractor overseen by Rody or me, mostly Rody, because I was having babies at that point. Then Stan, after [a time], set himself to scraping off all the old paint. He did a huge amount, but when it came to doing the staircase and all the spindles on three flights of stairs – well two flights of stairs – well, three, we never did the third until much later – we hired somebody to come in and do that, because it was too much on his (11:00) schedule. The smell of burning paint is still in my memory; the smell of old, abandoned houses is in my memory. Every now and again we’ve been into one in more recent years, and like, “Oh, yes, I remember that smell so well.” Dank, old, no air coming in.

DS: You had your first child, Katrina –

EB: [May] I back up a minute, because there’s a wonderful story about the restoration, if that’s OK?

DS: Oh, sure.

EB: We had a storefront on the house, and the Historical Commission told us that we had to put back, in place of the storefront, new brick matching the old and two windows. The house overall is only seventeen feet wide, but on the first floor there’s an alleyway, so it’s actually only fourteen feet wide. To have a front (12:00) door and two windows was going to mean that they were going to be really narrow windows, and the shutters wouldn’t work right. We went to them and said, “It would be so much better to have one big window instead of two skinny ones.” “Oh, no, that’s the correct way to do it,” they said. I decided to go do some research in Stephen Girard’s papers, which are on microfilm at the American Philosophical Society. I spent hours cranking through. He never threw anything away. I finally found the records of the building of these houses: the four houses on Second Street plus the ones right behind on Philip Street. [They] were the property of John Cadwalader, who had built a magnificent house on the site in the 1760s. After his death and, of course, the decline of Second Street in general, his family decided to sell the house. It was (13:00) auctioned in 1805 – no, excuse me, in 1810 – and Stephen Girard bought it. In 1816, he tore it down, started building these new houses, and recycled a great deal of the materials from the eighteenth century house. About a third of the bricks he used were the old bricks, and we have a lot of them. You can see them in the kitchen. Anyway, I finally found the bill from the glazier, the person who made the window panes. I went through the bill and found all these different sizes of panes and finally hit on one set of panes that was larger than the others. There weren’t two windows there. It was one set (14:00) of large panes of glass. I went back to Rody and I said, “Rody, one window in front.” He said to me, “You know what?” His wife, Peggy, had been talking to a neighbor on American Street who had lived in the neighborhood since her childhood. She remembered skipping rope down Second Street as a child and that the house had one big window. Armed with that, we went back to the Historical Commission and said, “This is what it’s going to be.” They said, “OK.” It was great fun finding that. I was going back over my notes this past summer, and there’s a whole lot more that I need to bring out. Like, I found out about the recycled bricks. The house probably wasn’t finished until 1817, but it started construction in 1816. It’s pretty (15:00) interesting.

DS: A lot of work.

EB: A lot of work. Also, the house was built on cedar pilings because Little Dock Creek runs underneath it, down into Dock Creek and into the Delaware River.

DS: It’s underneath your house?

EB: It’s underneath our house. We have a French drain in the basement which always has water in it. Rody told us if the water ever went away from there, we need to be worried because that would mean the cedar pilings – it’s probably petrified by now –

DS: If the water went away?

EB: If the water went way down, the foundations of the house could be in trouble.

DS: What was the condition of the basement? Was it mud?

EG: No, it had a cement floor. I think in back – it was still mud in the back (16:00) section of it. I think it was. We had a termite inspection once – oh, no, no. It was the workmen when we were restoring the house said it was absolutely impossible to drill into the beams holding up the back part of the house. The front part they had to change, because they had to lower the floor – I mean they had to raise up the floor – so those original beams were gone. But, the ones in the back were the original ones, and they said they were so hard that they broke their drill bits on them; not like what we have today.

DS: The beams in the front you had to replace. Did you put cedar back in?

EB: I don’t think so.

DS: Have you had a termite problem? (17:00)

EB: Well, we have, but not drastic. More on the outside, in the back of the house.

DS: Does that French drain cause any trouble, as far as moisture in the house?

EB: When it rains a lot, it fills up.

DS: It doesn’t run over.

EB: It comes out some. It’s just a stone floor around it, so it doesn’t matter.

DS: Your first child, Katrina, in the sequence of restoring your house, was she born during the restoration?

EB: Well, let’s see, when we moved to Society Hill, I was teaching [French] at Springside. I wanted to keep teaching so I got a part-time job (18:00) teaching French at St. Peter’s School, which I had for two years. Katrina was born in the fall of 1967, and we moved into the house in the spring of 1968, so she was a baby, and then Whitney was born in March of 1969. That whole period of restoring the house, moving in, being pregnant, having the babies, and dealing with all that stuff, it was a busy time. I stopped teaching then and devoted myself to my children.

DS: You bought the house from the Redevelopment Authority, and they had some restrictions on the outside of your house, which you dealt with. Do you remember how much you paid for the house? (19:00)

EB: We paid around $10,000 for the house.

DS: The amount for restoring you put into it? Just approximately?

EB: You know, I can’t remember exactly, but I think it was around $75,000.

DS: And taxes?

EB: You mean at that time?

DS: Yes.

EB: I don’t know. It was a lot less than they are now.

DS: Loans from a bank?

EB: We got a mortgage.

DS: Was that a problem?

EB: No.

DS: Did you have any problem finding a bank?

EB: No, my husband was a lawyer in Center City, and he knew bankers and stuff. It was never a problem.

DS: Tell me about what it was like raising your children in this – did you feel it was difficult, more so than your friends? (20:00)

EB: Well, it was a lot more fun, I think, because we were out walking around all the time with the baby carriage and the stroller and whatnot. It was more of a challenge than other places, but it was great. Of course, we were living on three floors, which has always been a challenge, but a good one. The kids’ bedrooms – all of our bedrooms – were on the third floor, so there was a lot of up and down. They loved being out on the street when they got old enough to ride their tricycles. We had the wonderful experience of an old man named Bill, who lived in a boarding house around the corner from us on Spruce Street.

DS: On Spruce Street?

EB: He liked to come and sit on the steps of 302 S. Second Street (we’re 306) (21:00) and smoke his cigar. He was a retired longshoreman. He worked on the docks for his whole career. He had a daughter who lived in the Northeast, but he didn’t want to live with her. He wanted to be on his own. He was just kind of a fixture in the neighborhood. He was so nice. I’d come back from getting the groceries or something, and he’d say, “Somebody came to your door. They said they’d be back later.” Or “There’s a package.” Or he’d hold a package for us. He was what we called “being the eyes on the street.” We gave him cigars for his birthday. He was always a gentle presence around, and it was very nice. There was a bus stop in front of our house until, I don’t know, 30 years ago. There were people around and there was plenty of foot (22:00) traffic, so we always felt very safe. The house is totally surrounded in back, so it’s very hard for anybody climbing around back in there to get into our garden and our house. That was one reason we wanted to buy it, because we thought it was very secure.

Delancey Park or Three Bears Park opened up about that time, so that was a great magnet for us all, and much of the social life was there. We were all helped by the baby-sitting co-op. I couldn’t have managed without that. I think we all felt the same way: developing good relationships, friendships, with the other mothers (23:00) and the little kids and watching them all grow up together was really great.

We moved to Brussels in the spring of 1972, when our children were three and four years old. When we got there, we eventually moved into this nice house. It was within the city limits of Brussels, but it was a residential neighborhood. We had big lawn and garden in the back of it. It was lovely, but our children didn’t want to go there, even though it had a jungle gym and a swing and everything. They wanted to be out on the street, because that’s where the action was. They wanted to ride their tricycles on the sidewalk. [Laughs] It took a while for them to realize that they had this valued (24:00) asset, that other neighborhood children thought was a park. They wanted to come and play in our back yard. Our kids were, “You do? Why?” [Laughs] That was kind of neat to see.

Schooling was always an issue for all of us here. When Katrina started out, she went to the St. Charles Borromeo Montessori School at Twenty-second and Christian Streets, which was interesting. We had to schlep these kids – there were three or four kids in the neighborhood who were doing that, so we carpooled them back and forth. It was not a nice neighborhood then, but there was this big Catholic church there and the school was in the Parish house, I guess. A modern building. It was a wonderful school. (25:00) It was a great experience for Katrina. Just before we went to Brussels, Whitney was three in March, and we left in April, so that for the first part of that year he went to Three Steps Nursery School over at Old Pine. That was great. I don’t think it existed when Katrina started out. It was new just then. They ended up at St. Peter’s when we came back from Brussels in 1976.

DS: And finished through eighth grade?

EB: Yes.

DS: Tell me, what were the reactions of your family and friends when you and Stan made the decision not only to live there but to buy there?

EB: They were aghast. Incredulous, I guess is really the word. The reaction was, (26:00) “Number one, is it safe? Number two, where will you buy food?”

DS: Where did you buy food?

EB: When we lived in Society Hill Towers, there was a market in the basement. It was a convenience market. It was not like going to a supermarket, but it was there and when you needed something, it was great. Talk about safety: the guy that ran it was Tommy Giordano, and he always had a gun in his belt. We always felt perfectly safe [Laughs] I guess, so that was great. Before the SuperFresh was built at Fifth and Pine, we would go down to the Acme or whatever it was in South Philadelphia.

DS: Oregon Avenue?

EB: Oregon Avenue, right, exactly. That was the favorite place to ride ( 27:00) when somebody was feeling very, very pregnant, to bounce along the railroad tracks to get there along the riverfront, to hasten the arrival of whoever.

DS: Your friends said, “What about the crime? Groceries? Schools?”

EB: Yes, the whole thing. It was a developing neighborhood at that point, even though there were people already living here that had been here for many, many years. [When] so many of them left, it was like there was this vacuum that all these young folks were moving into, creating new institutions like the Civic Association, and bringing back the churches and the schools. I mean, St. Peter’s School was in pretty dire (28:00) straits at that time, and the infusion of all these young families really brought it back to life. I think that’s what made it exciting and worthwhile.

DS: Different?

EB: Yes. It wasn’t, certainly, living in Chestnut Hill, which was the last thing I wanted to do in my life. I spent my entire childhood there, so I wanted out.

DS: Tell me, when you started teaching at St. Peter’s School, was it co-ed then?

EB: Just. Maybe that year or the year before it had gone co-ed.

DS: Miss Seamans, had she come?

EB: No, it was before she came. The Rector, Joe Koci, was still running the school. I think the first year I was there, the school was still like the Choir School in that it was either third or fourth through ninth grades. The second year I was there, they (29:00) took it to first grade so they could start bringing in the younger children. I can’t remember when they did the nursery school, but that was like a big expansion of the school at that point. You know, the building situation was difficult. My classroom was actually the stage in the auditorium, which I shared with the art teacher. She had all her artwork on the walls, but I wanted to put up some French posters, so we had to negotiate on the space. It was perfectly decent space, but if anybody was using the auditorium, they had those folding, accordion style walls that you could open and close, and they weren’t terribly effective in keeping noise out. That was interesting. (30:00)

DS: Did you belong to St. Peter’s Church at that point?

EB: No, we didn’t. My father was an Episcopal minister in Chestnut Hill, and he was a good friend of Ernest Harding, the rector of Christ Church so, of course, we would go to Christ Church. We were like, “Well, maybe, maybe not.” Stan was on the vestry of St. Paul’s Church in Chestnut Hill at the time we were married so we went to St. Paul’s sometimes; we went to my father’s church, St. Martin’s, some of the time. We went to Christ Church occasionally. Whitney was baptized at Christ Church. It wasn’t until Lee Richards was coming, in 1970, that we began to turn our attention to St. Peter’s and started going. Then we left for four years [to go to Brussels]. It wasn’t until we came back in 1976 (31:00) that we got into St. Peter’s.

DS: You returned in 1976. How did you find the neighborhood changed? Anything that you remember that really struck you?

EB: I can’t think of anything startling off hand. There were more people, I guess. Most of the houses were restored by then, so it felt more substantial as a neighborhood.

DS: Tell me about your involvement in neighborhood organizations like the Civic Association.

EB: I wasn’t especially involved in the Civic Association. When there was an issue that came up, I was happy to help out; Stan was on the Board and very involved. I let him do that. I guess, skipping to later, [I had] these four-year chunks in my life, four (32:00) years pre-Brussels, four years in Brussels, and then the next stage begins. When we came back from Brussels, I got very involved with the Friends of Independence National Historical Park. I had, I guess in the early years of our marriage, become a park house guide at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, working in Fairmount Park. I did a lot with that and loved it. I was a history major in college and hated American history [Laughs] because it was so badly taught. In college, I never wanted to take any American history courses. I wanted to do European. Then suddenly here I was living in (33:00) the middle of American history, and I really got excited about it.

When we came back from Brussels, I thought why am I schlepping across town to go to the Art Museum and Fairmount Park to do what I love doing, when I could be doing it right here within walking distance? I was riding a bike around at that time, so it was great. I loved the park because it was the green grass for our kids. We would go over there and they would play around in the little Dock Creek place at Third between Walnut and Chestnut behind the Second Bank – I mean, the First Bank. I’m like, “This is something really worth supporting.” I got very involved with the Friends of INHP, starting in 1977 and started the Philadelphia Open House Tours with some other people, which began in 1979. I became Chairman, and my big project as Chairman was being in charge of the (34:00) creation of Welcome Park at Second and Sansom Streets, the William Penn commemoration. That was an amazing time for me to do that. We raised in the end, I think, $1.2 million for it. Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown were the architects, and it was really interesting and exciting. I learned a lot about William Penn, and it was something permanent, however you define permanent. It’s still there after more than twenty-five years now. It was a great project to be involved with.

DS: Was this during the period that Hobie Cawood was there? (35:00)

EB: Yes. I worked very closely with Hobie Cawood, Superintendent of the Park. He was wonderful to work with. His attitude, if he liked an idea, was, “If there’s a way to do it, we will,” instead of the more typical bureaucratic, “No, we don’t – we can’t do that.” He was always very open to new ideas and to bringing in the community to help promote the park and raise money for it. The Friends was founded so that money could be raised and not put into what they called the great black hole of Washington, the Interior Department. [Laughs] A separate nonprofit organization could raise money and then give it to the Park so it could go for the projects that the Park wanted. It was great fun to do that.

DS: A very stimulating time? (36:00)

EB: Yes. I wasn’t that involved in neighborhood organizations per se, unless you consider that, but that was more a city wide, region wide thing. Then, yes, well, got very involved in St. Peter’s School.

DS: Because the children went there?

EB: Because of the children.

DS: Did you go back to teaching?

EB: I did not. While the kids were there, I was on the board for a number of years, and then after Whitney graduated, I went back to the school as Director of Development, which I was for seven years. I loved doing that. I’ve been a teacher, a parent, a board member, and a staff person at that school. I saw it from all different vantage points. It was very exciting to work for that school. It’s a great place. When (37:00) I got to the point [that] my friends were St. Peter’s parents or parents of alumni – because most of our kids were out of school by the time I went to work there – when they started crossing the street when they saw me – I knew it was time to do something else. [Laughs] “Oh, no, she’s going to get me, get me to do something else. More money for St. Peter’s.” It was time.

DS: Another story?

EB: You were asking about my parents and reaction to my moving here. My father knew Christ Church pretty well, so they were here occasionally and knew the city. I had never seen Independence Hall until I was in college and a friend from (38:00) California came to stay with me over spring vacation. I said, “Oh, I’ll show you Independence Hall. I haven’t the slightest idea how to get there.” We did, and that was around 1960. I was like, “Wow, this is great!” My mother was an artist, and she – I don’t know if it was because of us moving into Society Hill or if this was an idea she already had – but it all kind of came about at that time.

She loved doing drawings of cities or towns or areas showing all the buildings in them, like an architectural drawing, but putting them in what she called a montage, so all together roughly geographically. If a house needed to be turned around, she would turn it around. She decided, (39:00) when she saw our apartment in Society Hill Towers, looking west out over the city, to do this picture of all of the city of Philadelphia. She would come in, walk around taking pictures, taking notes, doing little sketches, come and sit in our apartment, sketch from our windows. She loved it; she was thrilled that we were living there. She was nervous, I think, about us, but in the Towers we were safe. It was during those first years that we were there that she was working really hard on this. You know, constant, “Would you go and have a look at such-and-such and tell me does this have two windows or three windows?” and things like that. For her, it was a great adventure, and she loved it. Unfortunately, my father retired just at the time Katrina was born and they moved to Massachusetts. So, no more of that and no babysitter. For them, it wasn’t such a scary thing. (40:00)

DS: Thank you very much, Libby.

[End of Interview]

[Beginning of house history]

Beginnings

This Classical era house was built two hundred years ago, in 1816, by French-born Philadelphia sea captain, merchant, banker, real-estate developer and philanthropist Stephen Girard. It is one of a group of four he built on the site of Revolutionary War General John Cadwalader’s elegant Second Street mansion. The property was originally part of land granted by William Penn in 1681 to the Free Society of Traders for development of the southern part of the new town. It was the site of a spring running into Little Dock Creek called “Bathsheba’s Bath and Bower” where people would come out from the young town to get fresh water. Starting at about 4 th and Pine Streets, the creek still runs underground, is channeled into a storm sewer opposite the house and flows into the Delaware River.

In 1769 John Cadwalader purchased the house that builder Samuel Rhoads had erected in 1760. He and his bride, Maryland heiress Elizabeth Lloyd, did over the 38’ x 41’ mansion in the latest Georgian style and filled it with the finest Philadelphia furniture, much of which is now on display with portraits and other furnishings at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, as well as at the Metropolitan Museum in New York City. Cadwalader served admirably as one of George Washington’s most trusted generals in the American Revolutionary War with his company of infantry, dubbed the “Silk Stocking Brigade,” which trained in the courtyard behind the house. The Cadwaladers often entertained such people as Washington, Adams and other American founders in their elegant mansion. Sadly, Betsy died in February 1776, after the birth of their third child, and was buried in St. Peter’s churchyard. In the years following the Revolution, Cadwalader lived mostly in his Maryland house and married Williamina Bond in 1779. They had two children who survived infancy. Then, after taking a chill while duck hunting in Maryland, Cadwalader died in 1786 at the age of 44. His widow lived in the 2 nd Street house briefly, then rented it to her brother Phineas Bond. He had earlier moved to England as a Tory then returned to Philadelphia in 1786 as British Consul, thus making the Second Street house the British Consulate. When he left in 1792 the British ambassador lived there for three years.

Then after a number of years and owners, it was sold at auction in 1810 to Stephen Girard. By now Second Street was largely commercial and the grand mansions of the prior century were outdated and unappreciated. Girard tore down the old house and built four new houses as shops (of which three remain) with the shopkeepers living upstairs. A few years later, he built the houses on Philip Street, which had been the access to Cadwalader’s stables. All these houses were owned by the Girard Estate until 1932.

Browne Purchase

My husband Stanhope Browne and I moved into a rental apartment in the Society Hill Towers when we were first married, in October of 1964. We had attended a civic association house tour in May which included a model apartment in the Towers. We were both enchanted with the area and the apartment – and when we became engaged about a week later, the first thing we decided was that we wanted to live in Society Hill and take part in the exciting renewal of this historic neighborhood.

Redevelopment of the area was in full swing and many of the young couples we met were in the process of restoring old houses that they had purchased very inexpensively from the Redevelopment Authority (PRA). We caught the bug and soon determined that we wanted to do the same thing. We loved the village sense of the neighborhood where one could walk everywhere and meet one’s neighbors, knowing that these were the same streets walked by Franklin and other major figures in our country’s history. Furthermore, there was easy access by public transportation to the cultural life of Center City. We felt it was a place where we could raise children and be part of a lively and diverse community while contributing to the reclaiming of the city’s historic district.

We started looking around at empty, dank, uninhabited houses with Ted Newbold of the Old Philadelphia Development Corporation (OPDC), the organization tasked with making sales to individuals, which the PRA could not do. We looked at MANY houses and took into account condition, size, original details and location. We finally settled on 306 South 2 nd Street – and were told that another couple had just taken it. We then looked at #310 (#308 was already taken and #312 had been demolished for the Delancey Mews complex) but it did not have nearly as many original details as #306. But then, to our amazement and relief, the other couple withdrew because her psychiatrist had advised against her undertaking such a stressful project. After placing a $500 deposit on the house in December 1965, we purchased it in January 1967 for $9,800 – which we saw as expensive since the much older and larger house at the northwest corner of 2 nd and Spruce Streets had recently sold for $3,000! The house had been empty for seven years; it had previously housed the “Model Restaurant” which served kosher meals mostly to laborers on the nearby docks and at the Dock Street wholesale food market.

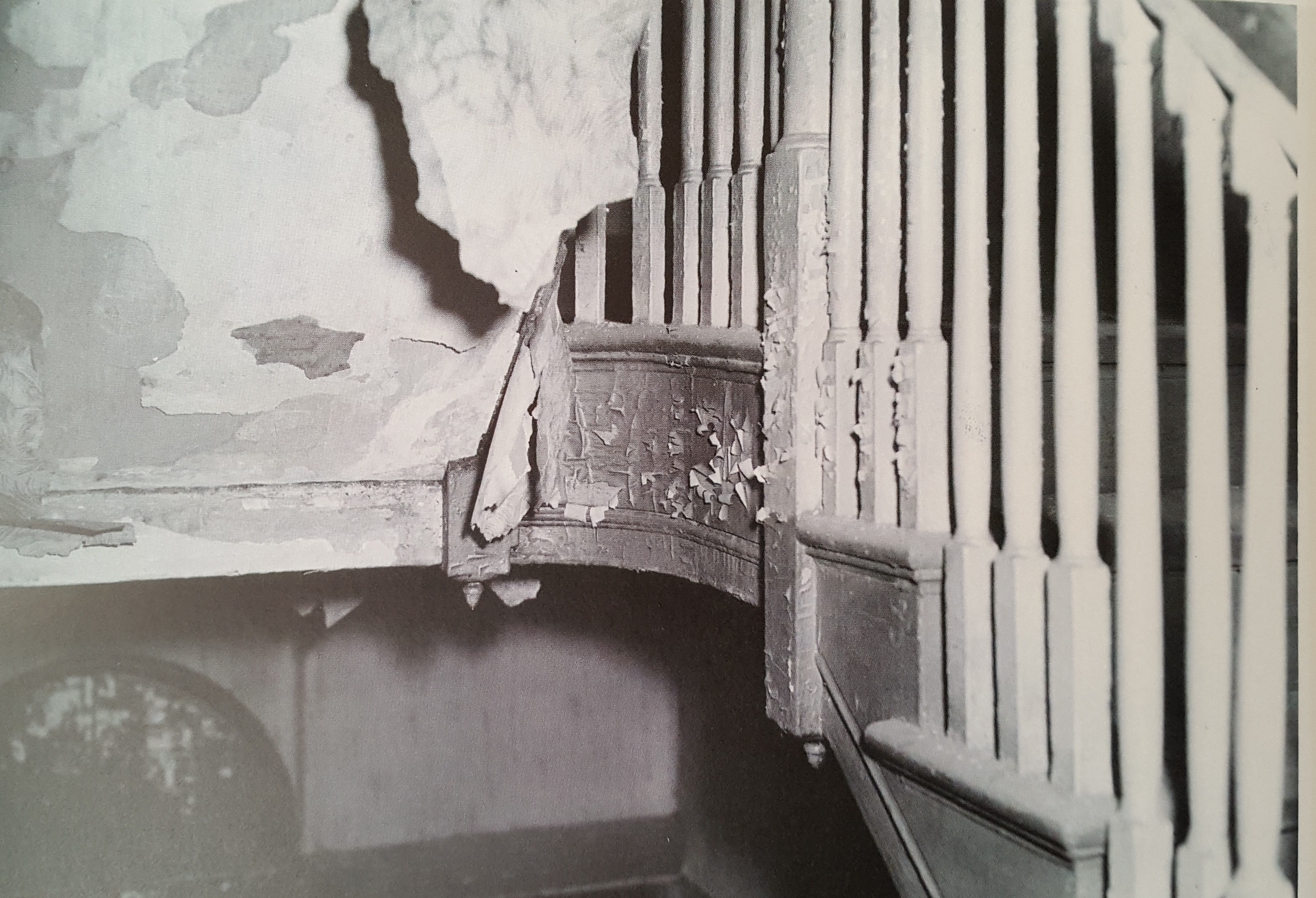

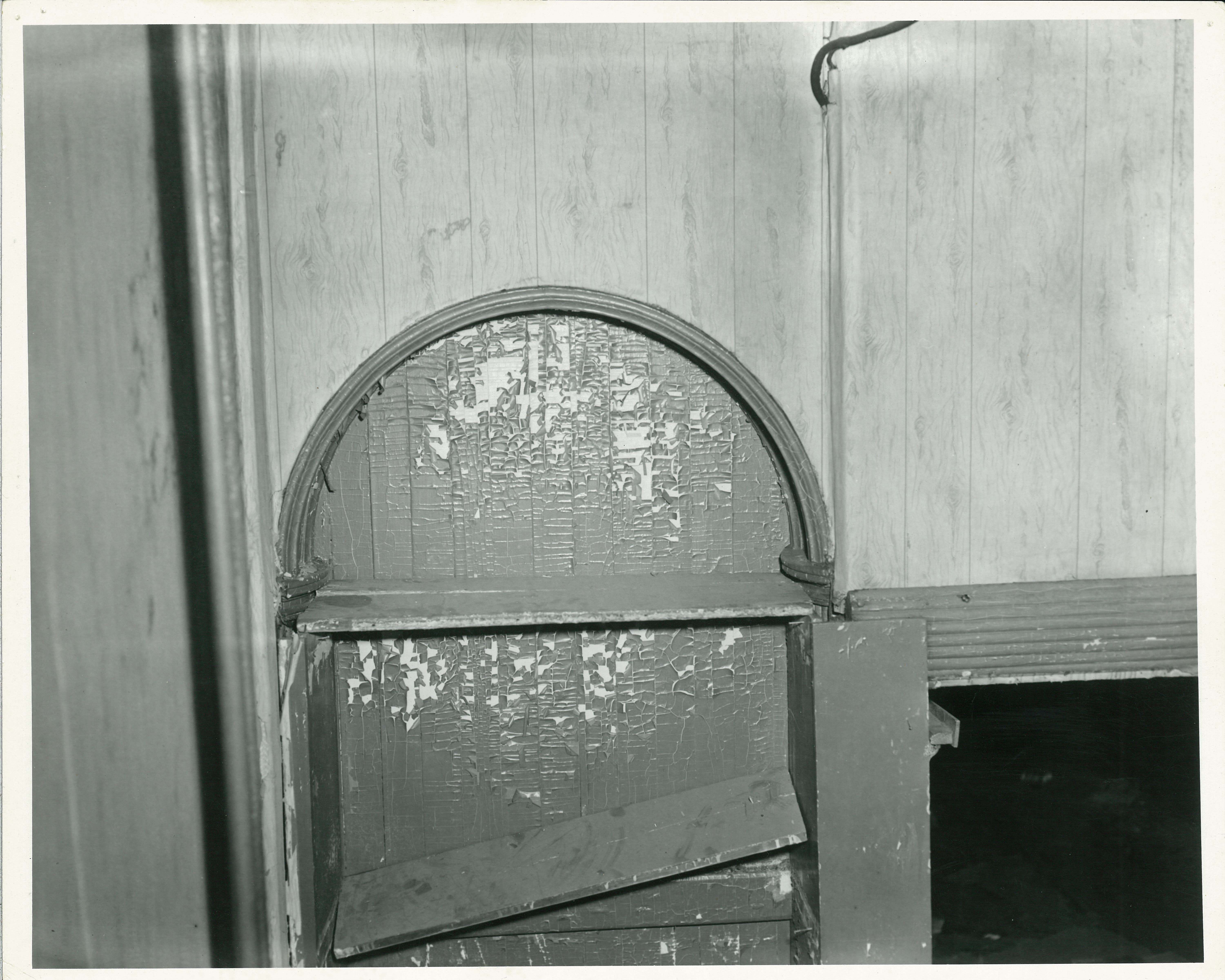

We engaged our neighbor, young architect Roland (“Rody”) Crocker Davies, to take charge of the restoration. Girard used good materials, and the house was very well constructed and, apart from the first floor where the restaurant had been, needed very little restoration once new electrical, heating and plumbing systems were installed. Elsewhere, all the floors, woodwork, Valley Forge blue marble mantelpieces and hearths, original staircase, archways with fluted pilasters remained. The oak beams which hold up the first floor back room (“the Snuggery”), although they have settled and caused the floor to slant, were so tough that the electricians were almost unable to put holes in them to run wiring, whereas the modern wood in the front part of the house where we had to replace the restaurant floor presented no problem at all.

During the restoration of the house, we had to resolve the question of whether to replace the existing large plate-glass storefront window with one or two period windows. The Historical Commission told us that it should have two windows, but because the house is only 14’6” wide on the first floor, we agreed with Rody that the windows would be much too narrow and that the shutters would have to overlap.

Being an old history major, I decided to do some research into the construction documents to see if I could find out what the original window arrangement had been. I learned that all of Girard’s papers had been put on microfilm and that I would be able to search through them at the American Philosophical Society on 5 th Street near Chestnut.

For several weeks I scrolled through the microfilms and finally found the bills from the glazier. It detailed the sizes and prices of the different panes of glass for the four houses on 2 nd Street that were built at the same time. I finally determined that there was one set of panes measuring 13”x 18”, larger than any others in the house, which would indicate one large window. I also found a bill for 64 marble windowsills, which number, when divided by 4, meant that there would be 16 per house. Since there were 15 still in place, that also would indicate one window in the first floor front. I also found the bill for the stone lintels, and this too pointed to a single, larger window size.

I also found that the buildings were planned as “houses and stores” so the probability of the front window being a larger shop window was strong. So armed with this significant evidence from my research, we announced to Rody that there was originally one large window. And then he told us that his wife Peggy had just asked a neighbor on nearby American Street, who had lived there all her life, if she remembered what the house looked like when she was a child. And she replied that she used to skip rope down the street, and that the house had one large window! So we were able to convince the Historical Commission with both scholarly and anecdotal evidence, in addition to the aesthetic considerations, that this was the correct thing to do.

I also discovered in my research that Stephen Girard was truly frugal. He saved everything, including tiny slips of paper showing how much he paid for his cigars. And in tearing down the Cadwalader mansion he recycled as much material as he could. We opened up one wall in our Keeping Room (first floor front) and found what are clearly 18 th century bricks, some of them glazed headers; when the wall in the library was opened up to install water pipes we found crown molding used as plaster lathing. In the papers I found a proposal from William Faries dated February 1816 for, among other things, “Taring down building cleaning & piling bricks $2 per 1000.” Later I found that Faries had cleaned 137,081 bricks. In September that year it is noted that they used 271,500 new bricks and 129,500 old ones.

In August 1816, Girard bought 117 cedar posts from Richard Willing. Because of the location of the houses on or near Little Dock Creek, Girard built his foundations on cedar pilings.

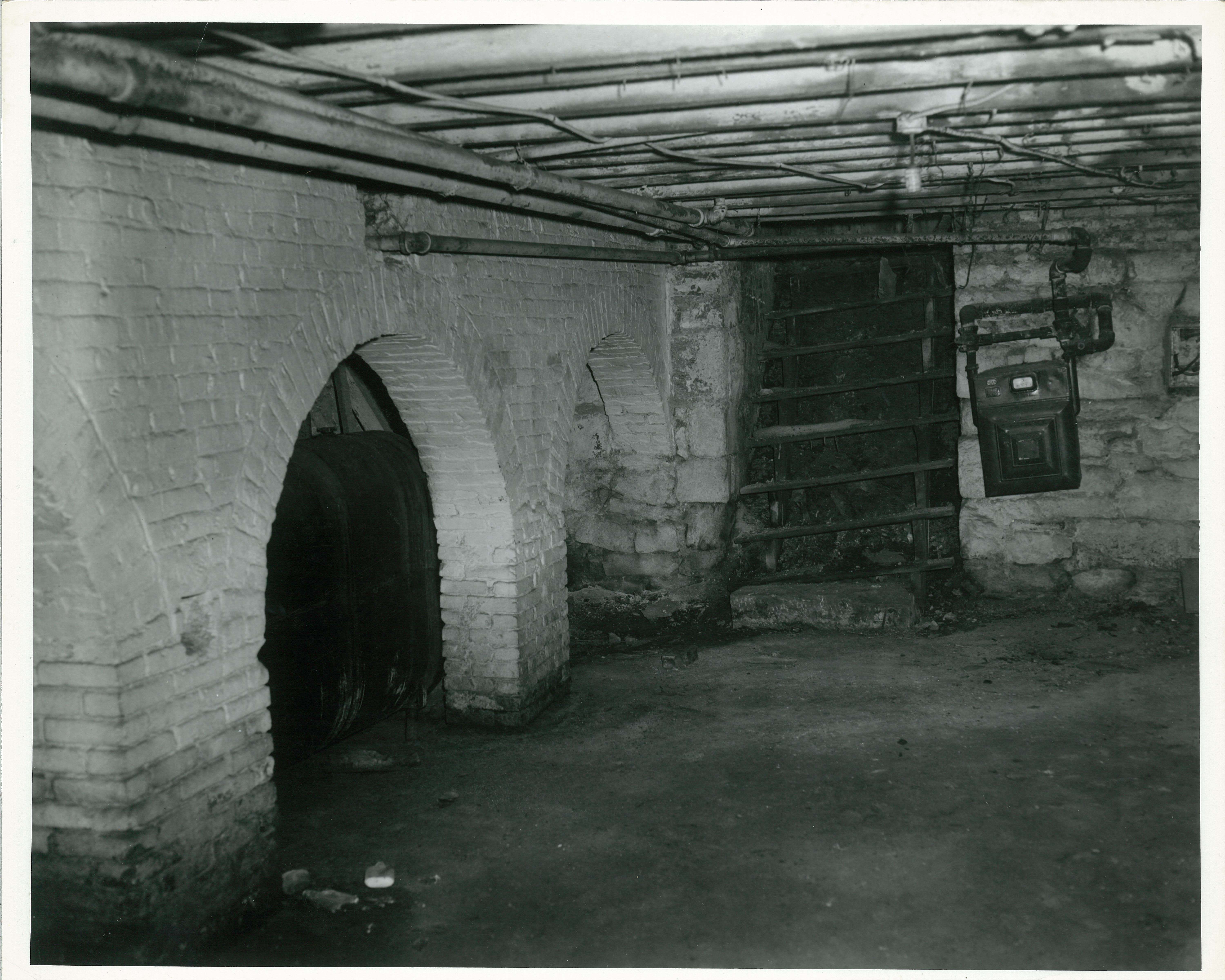

I was later fascinated to discover the explanation of this fact and for the placement of a hole about 10 inches square in the front of our basement which Rody told us was a French drain and that we should not cover it up. It had fresh water in it, generally about six inches below floor level and which never had algae or smelled bad. We covered it with some iron fencing.

Watson’s Annals of Philadelphia (vol. 1, p. 346) describes the location of the houses and the reason for the above:

“He [old Captain Benjamin Loxley (1719-1801) who built three brick houses on Spruce Street below Second before 1755] told them [his daughters] he had heard [Rev. George] Whitfield [sic] preach from the balcony of his house, No. 177 South Second Street, at the corner of Little Dock Street, and that there was a spring open then opposite, at the foot of a rising ground, on the lot where Captain Cadwallader [sic] lived, and where Girard has since built four houses. He had to drive piles to make the foundation over the spring. Samuel Coates has confirmed this same fact to me of the spring, and Whitfield’s preaching there.”

Later, on page 411, he describes the spring, called “Bathsheba’s bath and bower”:

“I had long heard facts concerning the rural beauty and charming scenes of Bathsheba’s bath and bower, as told among the earliest recollections of the aged. They had heard their parents talk of going out over the Second street bridge into the country about the Society hill and there making their tea-regale at the above-named spring. Some had seen it, and forgotten its location after it was changed by streets and houses; but a few, of more tenacious memories or observing minds, had preserved the site in the mind’s eye – among those was the late aged and respectable Samuel Coates, Esq.” [He goes on to describe the site and Whitfield preaching as in the quote above.]

Quoted from page 412:

“Mr. Alexander Fullerton, when aged 76 years old, told me he was familiar with this neighbourhood when a boy, and was certain the spring here was called ‘Bathsheba’s Spring and Bower.’ He knew also that the pump near there, and still at the south-east corner of Second and Spruce Streets, was long resorted to as superior water, and was said to draw its excellence from the same source.

When I first published my Annals, I had to make much inquiry and search, before I could fully determine the location of this spring. I since find, by the Rev. Mr. Clay’s Annals of the Swedes, that the whole place was named after and fitted up by the aunt of his grandmother, Ann Clay. Her name was Bathsheba Bowers. The MS life of Ann Clay read thus: ‘Under Society Hill she (Bathsheba Bowers, her maiden aunt) built a small house, close by the best spring of water that was in our city. The house she furnished with books, a table and a cup, in which she, or any that visited her, drank of the spring. Some people gave it the name of Bathsheba’s Bower, and the spring has ever since borne the name of Bathsheba’s Spring.

The street in front of Loxley’s house was originally much lower than it now appears to the eye, being raised by a subterrane[an] tunnel. It was traversed by a low wooden bridge half the width of the street, and the other half was left open for watering cattle.

The yards now in the rear of Girard’s houses are much above the level of Second Street, and prove the fact of a former hill there; on which Captain Cadwallader [sic] used to exercise and drill his celebrated ‘silk stocking company.’”

Restoration Begins

Our planning process with Rody Davies took a long time. We had to decide how to use the different rooms and he had various ideas for us to choose from. We determined that we wanted to have the first floor front section as dining room and kitchen, with the back devoted to what we named the Snuggery (a name for the back room of English pubs). This would give us quiet at the back of the house for our family room, and good access to the kitchen when bringing in groceries. We would maintain the elegance of the second floor front parlors where we could entertain, have a guest room at the back and then have three family bedrooms on the 3 rd floor. Rody came up with a plan for having the kitchen in the front of the basement with the dining room next to it with a cathedral ceiling, and a narrow hall going along the north side of it for access to the back of the house. We loved the drama of the plan, but I decided in the end that I did not want to spend hours in the kitchen below ground. Both of us had read Jane Jacobs’s book, Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), and I wanted to be able to perform the function of what she called “eyes on the street.” I would want to know what was going on outside, good or bad, and didn’t want to have to run up the stairs to find out. Another good idea that Rody had was to have the laundry on the 3 rd floor where the clothes would be, not as traditionally done in the basement – a long haul to the 3 rd floor!

Restoration of the house began in summer of 1967, about the time our first child Katrina was born. Rody and our contractor Carl Peterson did an extraordinary job of transforming the dark, dank structure into a light-filled space with as many original features as we could preserve. In the Keeping Room, the space at the front of the first floor next to the galley kitchen, we even removed the plaster and exposed the recycled Cadwalader bricks on the south wall. A table, four chairs, a home-made desk of two cabinets and a big piece of plywood which Stan stained and varnished for me made and a cork-board wall on the north side for posting notices, invitations, etc. made it an attractive and functional space.

At the time, the Redevelopment Authority was demolishing houses north of Center City for various reasons (they probably couldn’t get away with it now) and had a stockpile of old building materials such as marble sills, steps and fireplace pieces which were available to people restoring old houses in Society Hill. Because we had to replace the first floor façade, we availed ourselves of a number of these, such as front door steps, cellarway cheeks and sill, and eventually we found a perfect period fan light to put above the front door. With the doorknocker that my brother gave us which came from a house in Bristol, Rhode Island, of the same period, we created a beautiful entrance to our new home.

The old house had a fireplace in every room except on the first floor which had been turned over to the restaurant function. We decided to keep the ones in the front of the house, but the ones in the back which were in much smaller rooms we closed off. However, we wanted one in the Snuggery where the protruding wall indicated that there had been one originally. One of the most beautiful features of the house was the curved wall in the back section. Rody designed a curved hearth which would echo this wall at the front of the room, and to echo that he designed a curved opening with a round piece of slate where the andirons would be placed. When the workmen came to open up the old wall, they found the old fireplace – with a curved wall, just as he designed! They also found a small oven in the wall to the left of the fireplace, so from that we knew that this was where the cooking was originally done.

When we closed off the fireplace in the second floor rear room, we saw that it had in it a handsome fireback. We decided to remove it and put it in the living room fireplace where it could be seen and appreciated.

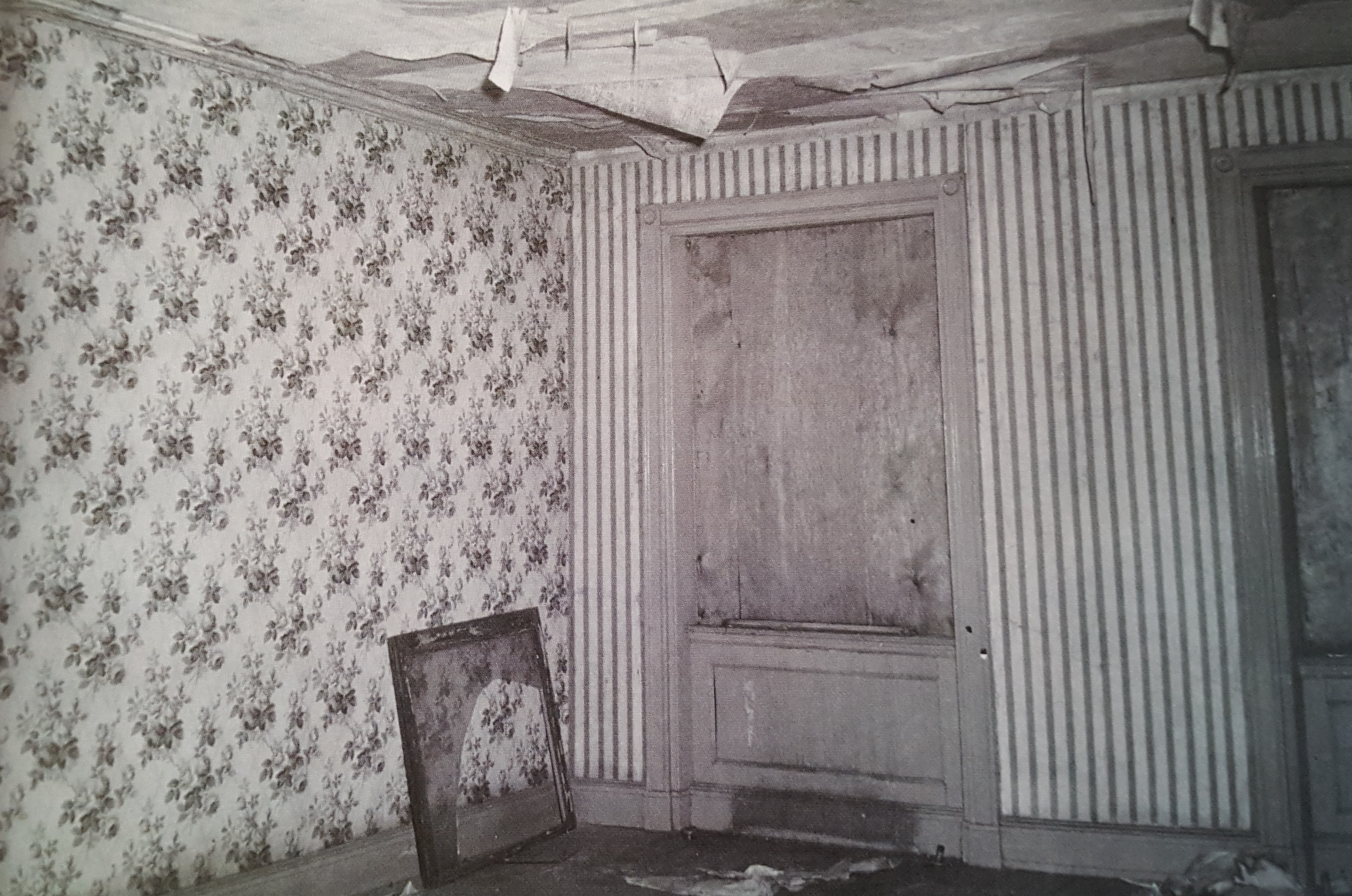

In May of 1968 we were thrilled to finally move in to a habitable house – new systems had been installed and first and third floor rooms and the staircase walls painted. A lot of work remained to be done, but at least we could be in the house and do what we could to complete the process. Stan took it upon himself to remove all the old paint – 11 layers! – in the living room and the library on the second floor. He spent hours on weekends scraping paint, using dental tools on the carved or fluted woodwork. The next job was the staircase with its many lovely balusters – and he decided that it was time to hire someone to do that.

We decided not to restore the second floor living room and library just yet, but we did remove the old cabbage rose wallpaper. The mottled walls that were thus exposed were not beautiful at all, but this would have to wait. We did invite people in occasionally to see the progress of the restoration, and at one party, a guest gushed over the walls, saying that this was just the effect that Jackie Kennedy had been looking for when restoring the White House!

We also decided to delay restoration of the attic, the basement and the garden. A two-story back wing that had been added to the original back wing was removed – it was probably used for bathrooms, but we saved the bricks and did nothing more at first.

Our son Whitney was born in 1969 and in 1970 it was decided that we would move to Brussels, Belgium, for four years where Stan would lead his law firm’s office there (1972-76). We figured that in order to rent the house while we were gone, we would need to put in a garden and should plant whatever trees we would want so they could get established while we were away. Rody came up with a garden design for us that we would execute when we came back, but it determined where the trees should go: a pin oak was planted in the northwest corner and a honey locust in the southeast corner to act as a shield for the house next door. A wall was built between the two houses, with iron fencing in the narrow space between them and stucco covered cinder-block between the two gardens. The long narrow space still had in it some old sheds which were removed, then Stan got busy and created a raised terrace across the back of the garden where one could sit and enjoy being outside. He had learned how to lay bricks as a teenager, so it was a great success.

Final Work

Once we got back in the summer of 1976 and got reestablished in the house and the community, we decided it was time to do the garden and also to restore the attic and the basement. Our children were growing and we needed these spaces for them as well as ourselves. We decided to move Whitney from the small room/laundry closet near our bedroom to the wonderful space in the attic, to turn the unfinished basement space to a play area and wine cellar and to finally implement Rody’s design for the garden.

Rody designed the attic to include two large closets to make up in part for the storage area we were giving up. He included a loft with access through a secret door and a boat staircase – very steep – and a skylight. He created a bunk-type bed with a desk at one end and room for Whitney’s European train set underneath. Zoning rules did not allow a bathroom on the 4 th floor, but we could put in a sink. The original dormer windows were refurbished and, lying in bed, Whitney would be able to see William Penn on top of City Hall.

For the basement, he designed a space that would require the removal of a row of arches along the north side that had originally supported the floor above. But because the arches had been cut down when a new floor was installed to make it flush with the sidewalk – probably for ease of access of restaurant supplies and patrons – they were no longer necessary for support, and the new floor we had installed did not need them. So we removed one of the two arches to create more space for a ping-pong table. There were handsome brick arches along the south side which we retained. The insulated but not refrigerated wine cellar benefited from the presence of Little Dock Creek below, maintaining the desired 55 degrees all year ‘round.

Rody’s design for the garden echoed the curves of the wall and the hearth in the Snuggery and included raised (or “geriatric”) beds whose walls were topped in brick and served as ample seating for guests. In the top of the wall of one of the two higher beds was included a place for a Danish grill which we had brought back from Brussels. About midway along the south wall we made space for a fountain where at last we could install “Horatio,” a stone head with open mouth that we had purchased in Italy on our honeymoon. Stan labored mightily to create a spout that would send out water in a broad spray and not have what he had learned to disparage as a “dribble chin fountain.” He bought a Bunsen burner top and soldered it to the desired opening and then to the pipe which brought the water in from a circulating pump alongside the base of the fountain. It worked beautifully! We engaged friend and landscape designer Nonya Wright to determine what plantings would do well in a shade garden. Before work started the children and I performed a dig to see what artifacts of the prior owners of the property we could find. Fascinating!

Work started in the fall of 1978 and took about 6 months to complete. The small room on the 3 rd floor that had been Whitney’s bedroom became Stan’s office. At last the restoration of our beloved house was complete – all attic stairs which were painted a few years later. However since, according to Stan, Confucius said that nothing can ever be perfect, we left unfinished the closet under the attic stairs. We never changed the two shelves and various hooks that had been there, perhaps since the house was first built. Thank you, Stephen Girard, for a house which we thoroughly enjoyed for our forty-three years in it. May the Cusack family continue to preserve and appreciate it.

Sources for House History

Stephen Girard Papers, 1793-1857. American Philosophical Society.

Wainwright, Nicholas B. Colonial Grandeur in Philadelphia: The House and Furniture of General John Cadwalader. Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1964.

Watson, John F. Annals of Philadelphia and Pennsylvania, In the Olden Time; Being a Collection of Memoirs, Anecdotes, and Incidents of the City and its Inhabitants, and of the Earliest Settlements of the Inland Part of Pennsylvania. Vol. I. Philadelphia: E. S. Stuart, Co., 1905.

© 2009 Project Philadelphia 19106™. All rights reserved.

Elizabeth Browne

Photograph by Dorothy Stevens

306 S 2nd Street

306 S 2nd Street - basement

Collection of Elizabeth Browne