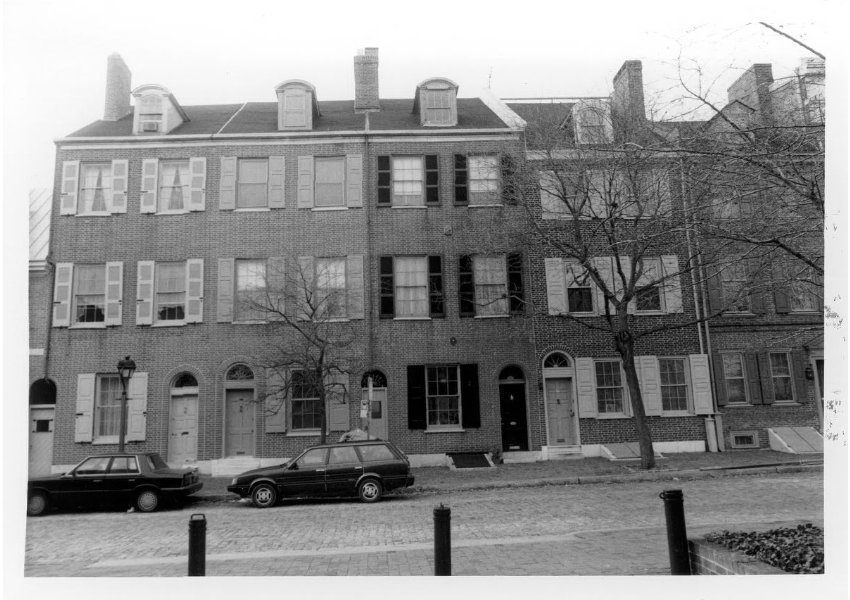

This property is one of four 3½-story Greek Revival row houses built in 1816 by merchant, banker, and real estate developer Stephen Girard on the former site of Revolutionary War General John Cadwalader’s Second Street mansion. Upon the four buildings’ construction, they included shops on the first floor and housing for the shopkeepers above. Girard also recycled some building materials (including bricks) from the original mansion in the new construction. Three of these four buildings still remain, with the last having been torn down for the construction of Delancey Mews in 1967.

In 1964, after Stanhope and Elizabeth (Libby) Browne married, they moved from Chestnut Hill and Germantown, respectively, into an apartment in the newly-opened Society Hill Towers. But they soon “caught the bug” to renovate one of the nearby row houses. Libby later recalled, “We loved the village sense of the neighborhood where one could walk everywhere and meet one’s neighbors, knowing that these were the same streets walked by Franklin and other major figures in our country’s history. Furthermore, there was easy access by public transportation to the cultural life of Center City. We felt it was a place where we could raise children and be part of a lively and diverse community while contributing to the reclaiming of the city’s historic district.”

After looking at several available properties, the Brownes selected 306 S 2nd Street given its size, location, and the endurance of many original details. They purchased the property in 1965 for $10,000. By that point, the building had been empty for seven years, having last housed the Model Restaurant, which served kosher meals to a clientele consisting primarily of laborers from the nearby docks and Dock Street wholesale food market.

The couple hired their neighbor, architect Roland Davies, to lead the restoration. Davies had recently graduated from the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Fine Arts, and he and his wife purchased a row house of their own to restore on South American Street. A local contractor, Carl Peterson, completed the major renovation work between the summer of 1967, when the Brownes’ first child was born, and May 1968, when the family first began occupying their new home.

On the exterior of the building, the restoration of street-facing windows posed a dilemma. In place of the large first floor plate-glass storefront window, the Historical Commission recommended the insertion of two double-hung windows beside the doorway. But, both owners and architect felt these would be too cramped given the building’s 14’ 6” first floor width; so Libby turned to Stephen Girard’s papers, held at the American Philosophical Society, for historical research. After uncovering receipts for sills, lintels, and glass panes, she determined that there had originally been one large first floor window. A long-time resident of the area also confirmed this arrangement anecdotally. This proof convinced the Historical Commission to approve a single large first floor window design instead. For other exterior elements, the contractor salvaged building materials from demolished houses in the area. These included front door steps, cellarway cheeks and a sill, and a period fan light to put above the front door.

Inside, the new owners collaborated with Davies to work out a suitable layout. Libby recalled, “We determined that we wanted to have the first floor front section as dining room and kitchen, with the back devoted to what we named the Snuggery (a name for the back room of English pubs). This would give us quiet at the back of the house for our family room, and good access to the kitchen when bringing in groceries. We would maintain the elegance of the second floor front parlors where we could entertain, have a guest room at the back, and then have three family bedrooms on the 3rd floor.”

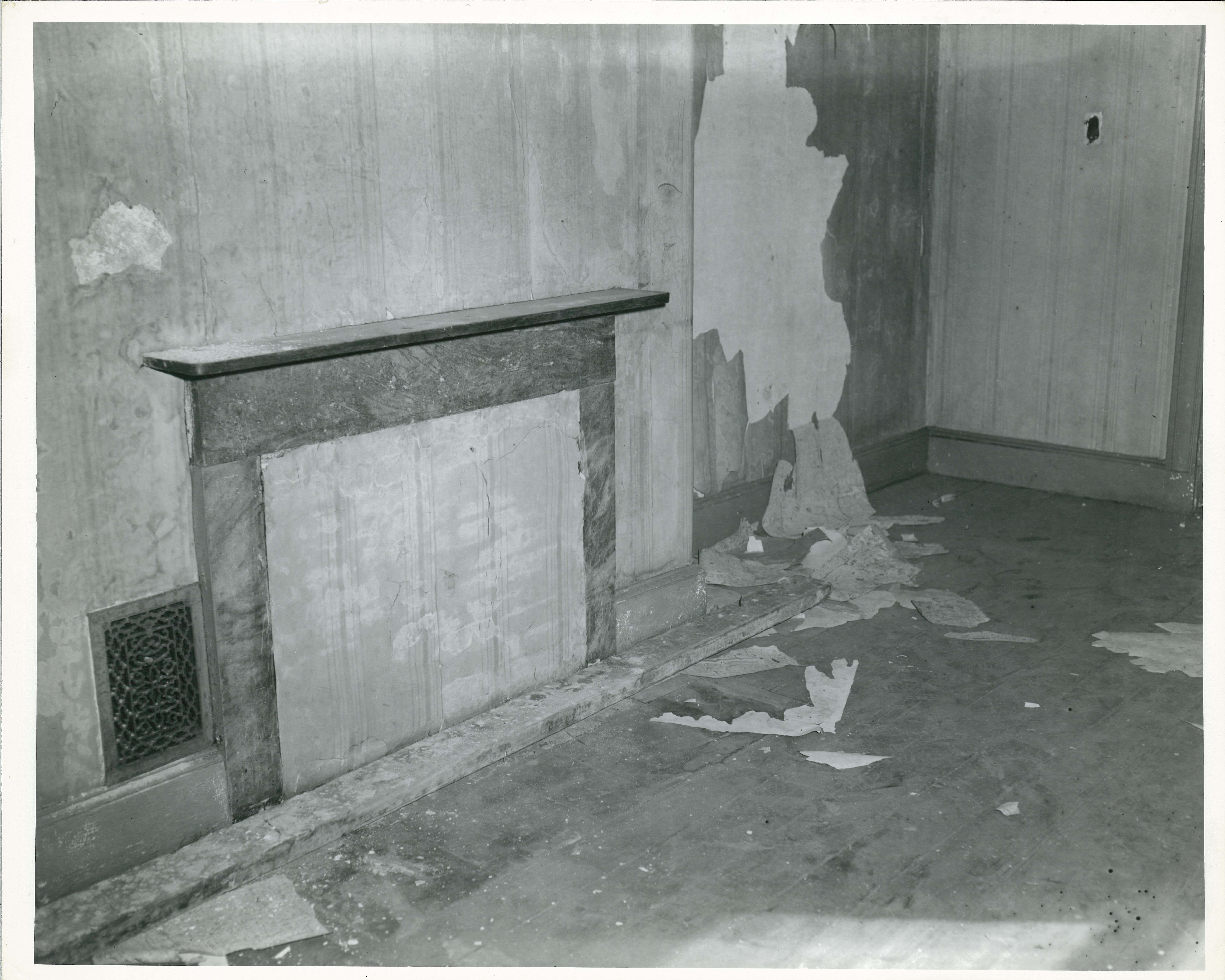

In terms of materials, they worked with existing elements where possible and incorporated new additions in keeping with the original period and architectural style of the building. The upper levels were pretty well intact, including the floorboards, staircase, woodwork, Valley Forge blue marble mantelpieces and hearths, and archways with fluted pilasters. They closed off the fireplaces in many of the smaller rooms, while also opening up one that had previously been closed in the Snuggery section. There, Davies designed a curved hearth to echo the curved wall already present. They also updated the major systems and removed a two-story addition off the back of the house, saving the bricks for future use.

After the Brownes were in residence, they continued the renovation work. They scraped paint off the walls and staircase and also removed old wallpaper. Over time, as their family grew, they renovated the basement into a playroom and wine cellar, and the attic into a bedroom and storage closets. Lastly, they worked with a landscape architect to design the garden space.

During their tenure, the Brownes became heavily involved with neighborhood life. Stan Browne leveraged his professional skills as a lawyer to lead the successful 15-year effort to depress and cover Interstate 95 as it passed beside Society Hill. The city recently announced plans to expand the size of that highway cap, in keeping with the proposal of the Gateway Committee that Stan had headed. Libby Browne taught at St. Peter’s School and also helped lead several history-based projects in the area. In 1977, she became involved with the Friends of Independence National Historical Park. In 1979, she helped start the Philadelphia Open House Tours. As Chairman, she oversaw the creation of Welcome Park at Second and Sansom Streets, which was designed by Venturi Scott Browne.

The Brownes owned the property until 2017, when they sold it to the current owners.

This narrative draws upon Libby Browne’s house history and oral history interview, contained within the Project Philadelphia 19106 collection at the Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries and Preserving Society Hill. The website also contains a memoir of Stan Browne’s experience in helping to shape I-95.